Showboat

A showboat, or show boat, was a floating theater that traveled along the waterways of the United States, especially along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, to bring culture and entertainment to the inhabitants of river frontiers.[1] Showboats were a special type of riverboat designed to carry passengers rather than cargo, and they had to be pushed by a small (and misleadingly labeled) towboat, also known as a pusher, which was attached to it.[2] Showboats were rarely steam-powered because the steam engine had to be placed right in the auditorium for logistical reasons, therefore making it difficult to have a large theater.[3]

History

During the American frontier era, populations of potential audiences were widely scattered about the area that is now the United States. Actors traveled to America from England, and theatre venues as well as touring companies were developed. Noah Ludlow, an early pioneer in travelling theater, purchased a keelboat in 1816 for $200 and named it Noah's Ark. Ludlow and 11 associates, together known as the American Theatrical Commonwealth Company, climbed aboard and traveled down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, stopping to perform whenever they could. It is not clear whether they ever performed on the boat, or just used the boat as a means of travel. If they did, in fact, perform on the boat (as is probable),[4] then Ludlow's Noah's Ark would have been the first showboat.

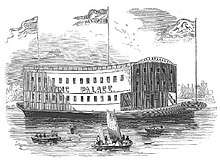

British-born actor William Chapman, Sr. created the first deliberately-planned showboat, named the Floating Theater in Pittsburgh in 1831.[1] He and his family of nine, along with two other people, lived on this boat and performed plays with added music and dance at stops along the waterways. The price of admission was anywhere from a peck of fresh vegetables to 50 cents a person. After reaching New Orleans, they got rid of the boat and went back to Pittsburgh in a steamboat in order to tour down the river once again the following year.[4] In 1836, the family was able to afford a new, fully equipped steam engine with a stage. In 1837, it was renamed Steamboat Theatre.

Many other showboats followed the Floating Theater onto the rivers in the following years, and some of them began to do other performances besides theater. One popular showboat during this period was the Floating Circus Palace of Gilbert R. Spalding and Charles J. Rogers, built in 1851, that featured large-scale equestrian spectacles. By the middle of the nineteenth century, showboats could seat up to 3,400 and regularly featured wax museums and equestrian shows.[1]

Showboats disappeared entirely with the advent of the American Civil War, but began again in 1878. Upon their revival, they tended to focus on melodrama and vaudeville.[1] Major boats of this period included the New Sensation, New Era, Water Queen, and the Princess. New inventions such as the steamer tow and the steam calliope greatly increased both territory and audiences, and Stephen Foster’s songs added charm to their simple programs.[1]

With the improvement of roads, the rise of the automobile, motion pictures, and the maturation of the river culture, the popularity of showboats again began to decline.[5] In order to combat this development, they grew in size and became more colorful and elaborately designed in the 1900s. The Golden Rod seated 1,400 persons; the Cotton Blossom, the Sunny South, and the New Showboat were floating theatre palaces.[1] With the burlesquing of these programs throughout the 1930s to attract sophisticated audiences, showboats ceased to perform their original function.

The last showboat to travel the rivers in authentic pattern was the Golden Rod in 1943.[1] The glory days of showboats are recalled by the Majestic, which is docked on the Ohio River in Downtown Cincinnati. Until 2013, she served as a venue for regular performances.[6]

Popular culture

In 1914, circus actors James Adams and his wife launched the James Adams Floating Theatre, a showboat that would tour the Chesapeake Bay and bring theatre to audiences in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. In the process of writing her 1926 novel Show Boat, Edna Ferber stayed on board the James Adams Floating Theatre to gather research material on the showboat, a disappearing American pastime.[7] This novel served as the inspiration for the award-winning Kern and Hammerstein Broadway hit, Show Boat (1927).

Since the box-office success of MGM's 1951 motion picture version of the musical Show Boat, in which the boat was inaccurately redesigned as a deluxe, self-propelled steamboat, the image of a showboat as a large twin-stacked vessel with a huge paddle wheel at the rear has taken hold in popular culture. Two earlier film versions of Show Boat and most stage productions feature a historically accurate vessel, and Edna Ferber's novel on which the musical is based gives a description of the Cotton Blossom that accurately reflects the design of a nineteenth-century showboat.[8]

"Showboat" as a verb

Based on the supposedly gaudy look of showboats, the term "showboat" also came to mean someone who wants his or her ostentatious behavior to be seen at all costs. This term is particularly applied in sports, where a showboat (or sometimes "showboater") will do something flashy before (or even instead of) actually achieving his or her goal. The word is also used as a verb. British television show Soccer AM has a section appropriately named Showboat, dedicated to flashy tricks from the past week's games.

Oft-cited examples of showboating include Leon Lett's grocery-bag-carrying of a recovered football (which was then swatted out of his hand before the goal line) in Super Bowl XXVII; Bill Shoemaker's standing in the saddle before the finish line of the 1957 Kentucky Derby, costing him the win (some sources say he merely misjudged the finish line, with the jockey ahead of him not standing up then); Lindsey Jacobellis' grab of her snowboard which caused her to crash right before the finish of the Snowboard Cross final at the 2006 Winter Olympics, costing her a first-place finish and a gold medal (she got a silver medal instead); Usain Bolt pumping his chest before winning the 100m final at 2008 Summer Olympics, likely adding one or more tenths of a second to his world record time of 9.69 seconds; and Mario Balotelli missing a shot on (soccer) goal when he unnecessarily tried it backheel. Showboating is likely to get this sort of attention when, as a result, the contestant doing it encounters a problem in the still-in-progress competition.

In boxing, showboating often takes the form of taunting, dropping one's gloves and daring an opponent to throw a punch, or engaging in other risky behaviors while the match is ongoing. Notable boxers well known for their showboating style include Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, Roy Jones Jr. and Floyd Mayweather Jr. Anderson Silva is a fighter in UFC notorious for showboating.

See also

- Old Profanity Showboat

- Goldenrod Showboat

References

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Showboat". Britannica.com. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- "What is a Showboat?". WiseGeek.com. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- Kreuger, Miles (1977). Show Boat: The Story of a Classic American Musical (First ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195022759.

- Graham, Philip (30 January 2014). Showboats: The History of an American Institution. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292775558.

- Sheets, Deirdre. "Showboats." Dictionary of American History. 2003. Encyclopedia.com. 22 Aug. 2016 <http://www.encyclopedia.com>.

- Radel, Cliff (10 September 2013). "It's curtains for Cincinnati showboat's theater". USA Today. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- Haynie, Miriam (September 1950). "James Adams' Floating Theatr e". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- "Smash Hit Broadway Musical Showboat Inspired by The James Adams Floating Theatre!" James Adams Floating Theatre. Web. 23 Jan. 2011.