Shashe River

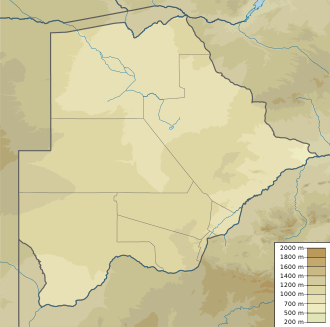

The Shashe River (or Shashi River) is a major left-bank tributary of the Limpopo River in Zimbabwe. It rises northwest of Francistown, Botswana and flows into the Limpopo River where Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa meet.[2] The confluence is at the site of the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area.

| Shashe River | |

|---|---|

Shashe River at Shashi Irrigation Scheme, Zimbabwe | |

| Location | |

| Country | Botswana, Zimbabwe |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | northwest of Francistown, Botswana |

| Mouth | |

• location | Limpopo River |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 462 million cubic metres per year (14.6 m3/s; 517 cu ft/s)[1] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Tati River, Ramokgwebana River, Thuli |

Hydrology

The Shashe River is a highly ephemeral river, with flow generally restricted to a few days of the year. The river contributes 12.2% of the mean annual runoff of the Limpopo Basin.[3]

Major tributaries of the Shashe River include the Simukwe, Shashani, Thuli, Tati and Ramokgwebana rivers. The lower Shashe is a sand filled channel, with extensive alluvial aquifers in the river channel and below the alluvial plains. These supply water for a number of irrigation schemes including Sibasa and Shashi.

More than two million years ago, the Upper Zambezi River used to flow south through what is now the Makgadikgadi Pan (presently a vast seasonal wetland) to the Shashe River and thence the Limpopo River.

Settlements

There is a road bridge and a rail bridge south of Francistown. The lower Shashe River forms the border between Botswana and Zimbabwe and is unbridged. However, at Tuli, both sides of the river are in Zimbabwe and there are two legal crossing points. The Shashi runs through the Shashi Irrigation Scheme and the Tuli Block.[citation needed]

Dams

The Shashe River is dammed near Francistown at Shashe Dam. The original purpose was to supply water to the industrial city of Selebi-Phikwe.[4] In 1982 it was found that groundwater from the local wells in Francistown had high levels of nitrate, and was also inadequate to meet public demand, so the public water supply for that city was changed over to using water from the Shashe Dam.[5] The dam also supplies water to surrounding villages, Phoenix Mine (Tati Nickel Mining Company/Norilsk Nickel) and Mupane Gold Mine (IAMGOLD).

Further downstream, the Dikgatlhong Dam impounds the Shashe near the village of Robelela, completed in December 2011.[6] When full it will hold 400,000,000 cubic metres (1.4×1010 cu ft). The next largest dam in Botswana, the Gaborone Dam, has capacity of 141,000,000 cubic metres (5.0×109 cu ft).[7] A pipeline from the Dikgatlhong Dam will connect to the North-South Carrier (NSC) pipeline at the BPT1 break pressure tank at Moralane. The NSC will take the water south to Gaborone.[8]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shashe River. |

- Geological changes to the course of the Zambezi River

- Thuli River

- Mchabezi River

- Mathangwane Village

References

Citations

- A.H.M. Görgens and R.A. Boroto. 1997

- Shashe Sub-basin Archived 2012-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Görgens & Boroto 1997.

- Knight 1990, p. 402.

- Schmoll 2006, p. 284.

- Modikwa 2011.

- Dikgatlhong dam - Jeffares & Green.

- Paya, Matsiara, Bettesworth, et al. 2012, p. 3.

Sources

- "Dikgatlhong dam". Jeffares & Green. Archived from the original on 2012-09-29. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- Knight, D.J. (1990-06-01). "The proven usefulness of instrumentation systems on varied dam projects". Geotechnical Instrumentation in Practice: Purpose, Performance and Interpretation : Proceedings of the Conference Geotechnical Instrumentation in Civil Engineering Projects. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-1515-9. Retrieved 2012-09-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Modikwa, Onalenna (13 December 2011). "Dikgatlhong dam complete ahead of schedule". Mmegi. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 2012-09-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- B. Paya; G.T. Matsiara; I.J. Bettesworth; M. van der Walt; P. du Plessis; B. Bosman; D. Stephenson; N. Mbayi; A. Keabetswe (2012). "BOTSWANA'S NORTH SOUTH CARRIER 2 WATER TRANSFER SCHEME" (PDF). WISA 2012 conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- Schmoll, Oliver (2006). Protecting Groundwater for Health: Managing the Quality of Drinking-Water Sources. World Health Organization. p. 284. ISBN 978-92-4-154668-3. Retrieved 2012-09-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Görgens, A.H.M.; Boroto, R.A. (1997). "River: flow balance anomalies, surprises and implications for integrated water resources management". Proceedings of the 8th South African National Hydrology Symposium, Pretoria, South Africa.