Tsonga people

The Tsonga people (Tsonga: Vatsonga) are a Bantu ethnic group native mainly to Southern Mozambique and South Africa (Limpopo and Mpumalanga). They speak Xitsonga, a Southern Bantu language. A very small number of Tsonga people are also found in Zimbabwe and Northern Swaziland. The Tsonga people of South Africa share some history with the Tsonga people of Southern Mozambique; however they differ culturally and linguistically from the Tonga people of Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Vatsonga | |

|---|---|

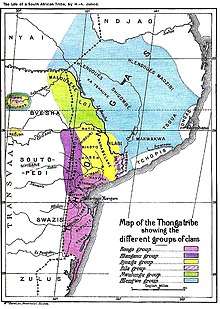

Traditional location of Tsonga people with dialectical differences and before the borders between Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Swaziland were imposed and the indigenous peoples were forcibly relocated by colonizers. | |

| Total population | |

| 7,470,000 (late 20th-century estimate)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Mozambique | 4,100,000 |

| South Africa | 3,300,000 (2019 population estimate, StatsSA) |

| Eswatini | 27,000 |

| Zimbabwe | 5,000 |

| Languages | |

| Tsonga, Portuguese, English | |

| Religion | |

| African traditional religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Bantu peoples | |

| Tsonga | |

|---|---|

| Person | Mutsonga |

| People | Vatsonga |

| Language | Xitsonga |

History

.jpg)

The Tsonga people originated from Central and East Africa somewhere between AD 200 and 500, and have been migrating in-and-out of South Africa for over a thousand (1,000) years. Initially, the Tsonga people settled on the coastal plains of Northern Mozambique but finally settled in the Transvaal Province and around parts of St Lucia Bay in South Africa from as early as the 1300s.[2] One of the earliest reputable written accounts of the Tsonga people is by Henri Philipe (HP) Junod titled "Matimu ya Vatsonga 1498-1650" which was formally published in 1977, and it speaks of the earliest Tsonga kingdoms. Before this, the older Henri Alexandri (HA) Junod released his work titled "The life of a South African Tribe" which was first published under two volumes in 1912-1913 and re-published in 1927.

The historical movements of the Tsonga people is dominated by separate migrations, with the Tembe people settling at the Southern parts of Swaziland around the 1350s and the Van'wanati and Vanyayi settling in the eastern Limpopo region between the late 1400s and 1650s.[3] Separate migrations from parts of Mozambique occurred shortly thereafter and particularly during the 1800s. According to historical records acquired from the Portuguese (who are perhaps the first Europeans to ship to African soil in the 1400s) and Swiss Missionaries who arrived to Mozambique and South Africa in the 1800s, Portuguese sailors encountered Tsonga tribes near the coast of Mozambique.[4] Early tribes identified are names such as the Mpfumo who belong to the Rhonga clan within the wider Tsonga (Thonga) ethnicity, and further identified during the 1500-1650 are the Valenga, Vacopi, Vatonga (Nyembana), Vatshwa, and Vandzawu.

The Vatsonga people from very early on were much like a confederacy where different groups settled and assimilated within a particular area and adopted a similar language that differed on the basis of geographic location (dialect). Various dialects of the Thonga/Tsonga language emerged from around the 1200s or earlier, such as Xirhonga, Xin'walungu, Xihlanganu, Xibila, Xihlengwe, and Xidjonga. They held large territorial areas in southern Mozambique and parts of South Africa and extracted tribute for those who passed through (paying tribute was to secure passage or to be spared from attack). The Tsonga tribes also operated like a confederacy in supplying regiments to different groups in the northern Transvaal region during times of Great Zimbabwe establishment and engaged in trade.[5] The Nkuna and Valoyi tribes which supplied soldiers to help the Modjadji kingdom; and the Nkomati and Mabunda tribes for supplying regiments to the army of Joao Albasini (Xipolongo empire). The Tsonga people have an age-old custom of leading their own tribes, with a senior traditional leader at the forefront of their own tribal establishment and is seen with a status equal to that of a king. The Tsonga people have lived according to these customs for ages and they hold the belief that "vukosi a byi peli nambu" which is a metaphor meaning "kingship does not cross territorial or family borders".

Within apartheid South Africa, a Tsonga "homeland", Gazankulu Bantustan, was created out of part of northern Transvaal Province (Now Limpopo Province and Mpumalanga) during the 1960s and was granted self-governing status in 1973.[6] This bantustan's economy depended largely on gold and on a small manufacturing sector.[6] However, only an estimated 500,000 people—less than half the Tsonga population of South Africa—ever lived there.[6] Many others joined township residents from other parts of South Africa around urban centres, especially Johannesburg and Pretoria.[6]

Name

The Constitution of South Africa stipulates that all South Africans have a right to identify with their own language, and points out that tribal affiliations or "ethnicity" is identifiable mostly through a common language; hence the recognition of groups such as, for example the Xhosas who are united by isiXhosa; Zulus who are united by isiZulu; Vendas who are united by Tshivenda; and the Sothos who are united by Sesotho. The various groups who speak the Xitsonga language or one of its dialects are therefore also united by the language and take its name from it, hence Constitutionally they are the Tsonga people (Vatsonga). There are also other Tsonga groups in parts of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Swaziland. Other related groups outside of South Africa who are ancestral or related to the South African Tsonga people go by various tribal names (e.g., Tonga, Rhonga, Chopi, Tswa) but they are sometimes classified within the heritage and history of the Tsonga people of South Africa.

Language

The Tsonga people speak the Xitsonga language, which is one of the official languages of the Republic of South Africa. According to historians, the Xitsonga language had already developed during the 1500s with its predecessor the "Thonga language" identified as the main origin.[2] It was mostly through the missionary work of the late 1800s to mid-1900s that led to a cohesive study of the Tsonga people's dialects and language features. The work carried out by Henri Junod and his father left a lasting legacy for the Tsonga people to rediscover their past history. It was however Paul Berthoud and his companion Ernest Creux who actively engaged with the Tsonga people of the Spelonken region to eventually produce the first hymn books written in the Xitsonga language at around 1878.[7] These Swiss Missionaries, however, did not understand the Xitsonga language at all and had to depend on the guidance of native speakers for the translations. The first book written in the Xitsonga language was published in 1883 by Paul Berthoud after dedicating enough time to learning the language. The Tsonga people themselves had then begun to learn to read and write in Xitsonga, however that the Tsonga people had already been well affluent in the Xitsonga language or one of its dialects long before the arrival of the Swiss Missionaries. There is evidence to indicate that the "language was already-spoken by the primitive occupants of the country more than 500 years" before the arrival of Swiss Missionaries.(Junod 1912, p. 32)[2]

Conflicts and naming conventions

The name "Tsonga" or "Vatsonga" itself is properly related to the older "Thonga" (also spelled as Tonga in some instances). The Thonga people are one of the original African tribes who left Central Africa between 200AD and 500AD and gave birth to many cultural identities in Southern Africa. The name "Thonga" has various meanings in different languages. In the Shona language it means "people of the river", or "kingless"; in isiZulu it means "ancestral spirits", "stick", "hunter", or "the prestigious ones". The Thonga people settled at various parts of southern Africa and thus different cultural identities were born who still identify with a common heritage. The Tembe people of KwaZulu-Natal, for example, still praise themselves as "amaThonga" but are now a part of the Zulu language and culture after being integrated in northern KwaZulu Natal.[8] The Rhonga people were identified according to the eastern direction from which they lived (Rhonga means East in the Rhonga dialect) and they included the tribes of Mpfumo of Nhlaruti, Nondwane, Vankomati, and Mabota. Another example is the Valenge and Chopi people (vaCopi) of Gunyule and Dzavana who are also related to the Tsonga people of South Africa such as the Maluleke, Shivambu, Mhinga, and Mulamula, and still regard themselves as part of the larger Thonga/Tonga group.[9] The tribes often identified as the Gwamba (properly the descendants of Gwambe) such as the tribes of Baloyi, Mathebula, and Nyai, also formed the Kalanga and Rozwi tribes. Other tribes include the Hlengwe people who are descended from those who called themselves Vatswa (sometimes spelled Tshwa) and also the Khosa who identified with the Djonga and Mbai sub-group. Indeed most of the Tsonga people of South Africa are descended from breakaway groups of the Thonga which must have happened around the 1600s with the dawn of the arrival of the Portuguese in Mozambique.[10]

In South Africa the name "Shangaan" or "Machangane" is regularly applied to the entire Tsonga population; however, this is a common misconception and others even take offense to it with regards to tribal affiliation.[3] What can be identified as the Shangaan tribe only forms a small fraction of the entire Tsonga ethnic group, meaning that the term "Shangaan" should only be applied to that tribe which is directly related to Soshangane ka Zikode (a Nguni general from the Ndwandwe tribe) who came to power during the 1800s, as well as those tribes which were founded or assimilated directly by him. In contrast, the Tsonga ethnic group comprises various tribal identities, some of which have been recognised and well established in Mozambique and South Africa even back around 1350 all the way through the 1600s to 1900s, namely the Varhonga, Vaxika, Vahlengwe, Van'wanati, Vacopi, Valoyi, and others. On the other hand, the double barrel term "Tsonga-Shangaan" is often applied in a way similar to Sotho and Tswana; Pedi and Lobedu; or Xhosa and Mpondo. Historical research shows that a substantial number of Tsonga tribes have been living together in South Africa during the 1400s to 1700s at a time where the name "Shangaan" had not yet existed.[4] Back during the 1640s-1700s the Tsonga people of South Africa were already integrated and living together established under their own traditional leaderships (such as the kingdoms led by Gulukhulu, Xihlomulo of the Valozyi, Maxakadzi of the Van'wanati, and Ngomani of the Vaxika).[11]

When Soshangane (whom the name "Shangaan" is taken from) and other Nguni invaders raided Mozambique later during the 1820s, the Tsonga people who were already living prior under Dutch colonialism in South Africa did not form a part of the Nguni Shangaan empire (and were often hostile to it) and they had already been speaking the Xitsonga language through dialects such as Xin'walungu, Xihlanganu, Xidzonga, etc. within the Transvaal.[12] Such Tsonga tribes have never been subjects of the Gaza Shangaan empire and have always retained their senior traditional leadership even during the governance of the Apartheid homeland system.[10] The misconception that they were all united by a single leader appears to be false as most of the people who organised the early Tsonga/Tonga groupings would still be integrated within South Africa even if the Mfecane Nguni wars did not happen. In addition to this, many of the Tsonga tribes who were still in Mozambique and later attacked by Soshangane and other Ndwandwes in the 1820s distanced themselves and fled to the Transvaal to re-establish themselves outside of the influence of the Gaza empire (they refused to be led by the Ngunis), while some remained and were either subjugated or enslaved.[13] Having said that, it is well known that the Gaza Empire was vast and included areas occupied by the Tsonga. Many Tsonga identified themselves as Shangani and there is a wealth of Nguni names and workds in their language which testifies of the Gaza Nguni rulership of these groups. The Copi people (Chopi) howeverclaim that they remained rebellious and independent throughout the lifetime of the Gaza kingdom and were never properly defeated,[14] and when the ruler of Gaza (Nghunghunyana) invaded their territory near the Limpopo River and attempted to subjugate them in 1888, a war ensued between the Chopi people and the Gaza forces that effectively lasted from 1889 and ended in 1895 when Nghunghunyana was defeated by the Portuguese (led by their general Mouzinho de Albuquerque) in alliance with Chopi soldiers (led by their king Xipenenyana).[15] Many of the Gaza people fled from the disintegrated Empire and its remaining leadership took asylum in South Africa where most of the Tsonga people had been living before the Mfecane wars started. In South Africa, the Gaza-Shangaan people lost their Nguni language which was prevalent within the Empire due largely to the new reality and they adopted the Xitsonga language in the Transvaal but still largely identify with Nguni customs.

In modern South Africa, the integration of such tribes has led to a social cohesion drive where some of the Tsonga people believe they face an identity crisis as a result of perceived tribalism of the Ndwandwe Shangaan tribe against the original Tsonga tribes.[16] Another factor is the Gaza-Shangaan people's association with a history of oppression and exploitation that the inhabitants of Mozambique suffered under the rule of the Gaza Empire during the 1800s, which has been well-documented by reliable sources and is a subject of much controversy and debate.[17][18]

Clan structures

The Tsonga ethnic group has been united by the gradual assimilation of various nearing tribes found in abundance within Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and South Africa respectively. Historical research indicates that the development of a common language (Xitsonga) as well as cultural integration within the Tsonga ethnic group has been occurring ever since the 1200s (over 800 years ago).[3] It is possible that different conflicting groups sought to establish protection alliances and thus integrated their tribes into a common establishment or to secure trade. Language appears to be the dominant factor in uniting the Tsonga tribes, similarly to the Venda people who are also of various tribes united by the Venda language. It is distortion of Tsonga history to say that the Tsonga people have never been united by a single royal family (Hlengwe) but by various tribal kingdoms that fought for dominance over time, who were eventually overcame by internal conflicts as well as the impact of colonial rule. However there is evidence to suggest that the earliest most dominant Tsonga kingdom within South African territory from the 1600s to the late 1800s was the Hlengwe Dynasty of Mahimi Mkhumuli Mabasa/Chauke and in the late 1900s was the Mhinga Dynasty, who founded Malamulele (the Rescuer) and further formed the leadership of the Gazankulu territorial authority around the 1960s in what is today the eastern parts of the Limpopo province.[19][20] The Van'wanati clan according to Henry A. Junod (1912) are also the ones who re-assimilated the Baloyi and Vanyayi clans who left the Kalanga country and became Tsonga-speaking.[2] However the Baloyi were part of the original Thonga cluster of clans (through their ancestor Gwambe) before they went to conquer parts of Zimbabwe and were nicknamed as Barozwi ("the destroyers"). The Tsonga people themselves still recognize their respective tribal origins and have also embraced the Tsonga national identity, which unites them linguistically and culturally within South Africa. The biggest factor in uniting the various Xitsonga-speaking tribes in South African territory is the role played by Sunduza II of the Mhinga Dynasty in 1961 where he mobilized all the Tsonga chiefs to form a territorial authority that enabled the Tsonga people to retain their own recognition equal to the Venda and Pedi territorial authorities (Mathebula 2002, p. 37).[3] Sunduza II Mhinga, a descendant of Dzavana and the king of the Chopi people Gunyule, began his pursuits to unite the Tsonga clans in the 1950s when the apartheid government attempted to assimilate the Tsonga and Shangaan people into the Venda and Pedi Bantustans. Sunduza II then called a meeting for all the leading Tsonga chiefs in 1957 and made a resolution to unite and resist the impending assimilation. The leadership by Sunduza II resulted in the apartheid government engaging in diplomatic talks which unilaterally granted the Tsonga people recognition to form their own territorial authority. This greatly cemented the unity between the Tsonga and Shangaan people from the formation of the Gazankulu Homeland where Hudson Ntsanwisi (a member of the Vanwanati clan) became the first Chief Minister of the Tsonga and Shangaan people.

Xitsonga-speaking communities of South Africa after 1890 (through a Xitsonga-related dialect or sub dialect):

- Vatsonga (Thonga, Tsonga,Xitanga)

- Amashangana (Ngoni, Ndwandwe)

Population

In total, there were 7, 3 million Tsonga speakers in 2011, divided mainly between South Africa and Mozambique. South Africa was home to 3,3 million Tsonga speakers in the 2011 population census, while Mozambique accounted for 4 million speakers of the language. A small insignificant number of speakers included 15 000 Tsonga speakers in Swaziland and roughly 18 000 speakers in Zimbabwe.[1]

In South Africa, Tsonga people were concentrated in the following municipal areas during the 2011 population census: Greater Giyani Local Municipality (248,000 people), Bushbuckridge Local Municipality (320,000 people), Greater Tzaneen Local Municipality (195,000 people), Ba-Phalaborwa Local Municipality (80,000 people), Makhado Local Municipality (170,000 people), Thulamela Local Municipality (220,000 people), City of Tshwane (280,000 people), City of Johannesburg (290,000 people), and Ekurhuleni (260,000 people). In the following municipalities, Tsonga people are present but they are not large enough or are not significant enough to form a dominant community in their shere of influence, in most cases, they are less than 50,000 people in each municipality. At the same time, they are not small enough to be ignored as they constitute the largest minority language group. They are as follows: Greater Letaba Local Municipality (28,00 people), Mbombela Local Municipality (26,000) people, Nkomazi Local Municipality (28,500) people, Mogalakwena Local Municipality (31,400 people), Madibeng Local Municipality (51,000), Moretele Local Municipality (34,000), and Rustenburg Local Municipality (30,000). The provincial breakdown of Tsonga speakers, according to the 2011 census, are as follows: Limpopo Province (1,006,000 people, Mpumalanga Province (415,000 people, Gauteng Province (800,000 people and North West Province (110,000 people. Overall, Tsonga speakers constitutes 4.4% of South Africa's total population.[1]

Economy

The Tsonga traditional economy is based on mixed agriculture and pastoralism. Cassava is the staple; corn (maize), millet, sorghum, and other crops are also grown. Women do much of the agricultural work,while men and teenage boys take care of domestic animals (a herd of cows, sheep, and goats) although some men grow cash crops. Most Tsongas now have jobs in South Africa and Mozambique.[21]

Culture

Tsonga men traditionally attend the initiation school for circumcision called Matlala (KaMatlala) or Ngoma (e Ngomeni) after which they are regarded as men. Young teenage girls attend an initiation school that old Vatsonga women lead called Khomba, and initiates are therefore called tikhomba (khomba- singular, tikhomba- plural). Only virgins are allowed to attend this initiation school where they will be taught more about womanhood, how to carry themselves as tikhomba in the community, and they are also readied for marriage.

The Vatsonga people living along the Limpopo River in South Africa have recently gained a significant amount of attention for their high-tech, lo-fi electronic dance music Xitsonga Traditional and otherwise promoted as Tsonga Disco, electro, and Tsonga ndzhumbha. The more traditional dance music of the Tsonga people was pioneered by the likes of General MD Shirinda, Fanny Mpfumo, Matshwa Bemuda, and Thomas Chauke, while the experimental genres of Tsonga disco and Tsonga ndzhumbha have been popularized by artists such as Joe Shirimani, Penny Penny, Peta Teanet, and Benny Mayengani. The more westernized type of sound which includes a lot of English words, sampled vocals and heavy synthesizers is promoted as Shangaan electro in Europe and has been pioneered by the likes of Nozinja, the Tshetsha Boys, and DJ Khwaya. The Tsonga people are also known for a number of traditional dances such as the Makhwaya, Xighubu, Mchongolo and Xibelani dances.

Traditional beliefs and healers

Like most Bantu cultures, the Tsonga people have a strong acknowledgement of their ancestors, who are believed to have a considerable effect on the lives of their descendants. The traditional healers are called n'anga.[22] Legend has it that the first Tsonga diviners of the South African lowveld were a woman called Nkomo We Lwandle (Cow of the Ocean) and a man called Dunga Manzi (Stirring Waters).[22] A powerful water serpent, Nzunzu (Ndhzhundzhu), allegedly captured them and submerged them in deep waters. They did not drown, but lived underwater breathing like fish. Once their kin had slaughtered a cow for Nzunzu, they were released and emerged from the water on their knees as powerful diviners with an assortment of potent herbs for healing.[22] Nkomo We Lwandle and Dunga Manzi became famous healers and trained hundred of women and men as diviners.

Among the Tsongas, symptoms such as persistent pains, infertility and bouts of aggression can be interpreted as signs that an alien spirit has entered a person's body.[22] When this occurs, the individual will consult a n'anga to diagnose the cause of illness. If it has been ascertained that the person has been called by the ancestors to become a n'anga, they will become a client of a senior diviner who will not only heal the sickness, but also invoke the spirits and train them to become diviners themselves.[22] The legend of the water serpent is re-enacted during the diviner's initiation, by ceremoniously submerging the initiates in water from which they emerge as diviners.

The kind of spirits that inhabit a person are identified by the language they speak. There are generally the Ngoni (derived from the word Nguni), the Ndau and the Malopo. The Ndau spirit possesses the descendants of the Gaza soldiers who had slain the Ndau and taken their wives.[23]

Once the spirit has been converted from hostile to benevolent forces, the spirits bestow the powers of divination and healing on the nganga.[22]

Notable Tsonga people

The following is a list of notable Tsonga people who have their own Wikipedia articles

- Brian Baloyi (South African footballer)

- Benny Mayengani (South African musician)

- Gito Baloi (Mozambican musician)

- Cassius Baloyi (South African boxer)

- Lucky Baloyi (South African footballer)

- Richard Baloyi (South African politician)

- Onalenna Baloyi (Botswana middle distance runner)

- DJ Brian (Radio personality, Club DJ and entrepreneur)

- Collins Chabane (South African politician)

- Thomas Chauke (Musician)

- Jackson Chauke (South African boxer)

- Joaquim Chissano (Former President of Mozambique)

- Lizha James (Mozambican musician and celebrity)

- Gonçalo Mabunda (Mozambican artist)

- Tiyani Mabunda (South African footballer)

- Graça Machel (Former first lady of Mozambique; former first lady of South Africa)

- Samora Moisés Machel (Former President of Mozambique)

- Sho Madjozi (South African musician)

- Jabulani Maluleke (South African footballer)

- Jeff Maluleke (South African musician)

- David Mathebula (South African footballer

- Herman Mashaba (Founder of "Black Like Me" and Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg)

- Oscarine Masuluke (South African footballer)

- Tito Mboweni (Minister of Finance of South Africa former South African Reserve Bank Governor)

- Edward Mhinga (Second Chief Minister of the bantustan of Gazankulu)

- Tsakani "TK" Mhinga (South African musician)

- Eduardo Mondlane (Founding President of FRELIMO)

- Hudson William Edison Ntsanwisi (Former Chief Minister of Gazankulu)

- Trevor Nyakane (South African rugby union player)

- Sam Nzima (Photographer of famous photo depicting the death of Hector Pieterson during the Soweto Uprising)

- Penny Penny (South African musician)

- Mbhazima Shilowa (former Premier of Gauteng)

- Floyd Shivambu (South African politician, Deputy President of the Economic Freedom Fighters)

- Eric Bhamuza Sono (Late South African footballer)

- Jomo Sono (South African football legend and owner of Jomo Cosmos)

- Akani Simbine ( South African sprinter)

- Pearl Modiadie(South African television presenter, radio DJ, actress and producer)

- Cassel Mathale(Former Premier of Limpopo)

- Daniel Cornel Marivate (South African writer and composer)

- Charles Daniel Marivate (South African medical doctor)

- Vonani Bila (South African author and poet)

- David Masondo (South African Politician,Deputy Minister of Finance)

References

- "Tsonga joshuaproject.net". Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- Junod, H.A (1912), The Life of a South African Tribe: The Social Life, Imprimerie Attinger Freres, Neuchatel.

- Mathebula, Mandla (2002), 800 Years of Tsonga History: 1200-2000, Burgersfort: Sasavona Publishers and Booksellers Pty Ltd.

- Junod, Henri (1977), Matimu Ya Vatsonga: 1498-1650, Braamfontein: Sasavona Publishers.

- "Great Zimbabwe". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Rita M. Byrnes, ed. (1996). "Tsonga and Venda". South Africa: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Harries, P 1987, The Roots of Ethnicity: Discourse and the Politics of Language Construction in South-East Africa, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Sowetan Live (2008), “Tembes on a Mission to Unify Tongas”, Retrieved on 11 October 2018

- Maluleke, V.M. (2013), "My Roots", Retrieved on September 29, 2018

- Mathebula, M, Nkuna, R, Mabasa, H, & Maluleke, M (2006), 'Tsonga History Perspective'.

- Theal, GM (1902), The Beginning of South African History, London: T.Fisher unwin.

- Junod, HA 1913, The Life of a South African Tribe: The Psychic Life, Imprimerie Attinger Freres, Neuchatel.

- "Forgotten History: The Gaza State, 1821- 1895". globalblackhistory.com. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Henri Philippe Junod (1927) Some Notes on T∫opi Origins, Bantu Studies, 3:1, 57-71, DOI: 10.1080/02561751.1927.9676196, viewed 4 December 2018

- Afrolegends (2013), ‘Gungunyane: The Lion of Gaza or the Last African King of Mozambique’, Retrieved 23 August 2018

- VivLifestyle (2017), 'Why does Munghana Lonene FM insist on labeling us as “Vatsonga-Machangani”?', accessed 11 October 2017

- Harries, P 1981, Slavery Amongst the Gaza Nguni: Its Changing Shape and Function and its Relationship to Other Forms of Exploitation, in JB Peires (ed.), pp. 210-229.

- Liesegang, G. (1986). Nghunghunyani Nqumayo: Rei de Gaza 1884-1895 e o desaparecimento do seu estado. Arquivo de Património Cultural.

- Witter, R. (2010), Taking their territory with them when they go: Mobility and access in Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park, Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Georgia.

- Bandama, F. (2013), The Archaeology and Technology of Metal Production in the Late Iron Age of the Southern Waterberg, Limpopo Province, South Africa, Doctors thesis, University of Cape Town.

- "Tsonga People". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Liebhammer, Nessa (2007). Dungamanzi (Stirring Waters). Johannesburg: WITS University Press. pp. 171–174. ISBN 978-1-86814-449-5.

- Broch-Due, Vigdis (2005). Violence And Belonging:The Quest For Identity In Post-Colonial Africa. Psychology Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780415290074. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

Bibliography

- Junod, Henri Alexandre (1927). The Life of a South African Tribe. London (second edition).

- The Fader – Ghetto Palms 90: New Styles/Shangaan Electro/South Africa Road Epic!

- Mandla Mathebula, et al. (2007). "Tsonga History Perspective".

- "First Online Tsonga Dictionary".