Shōnen Sekai

Shōnen Sekai (少年世界[note 1], "The Youth's World"), is one of the first shōnen magazines published by Hakubunkan specializing in children's literature, published from 1895 to 1914. Shōnen Sekai was created as a part of many magazine created by Hakubunkan that would connect with many different parts of society in Japan. Sazanami Iwaya created the Shōnen Sekai magazine after he wrote Koganemaru a modern piece of children's literature. After Japan had a war with Russia, a female adaptation of Shōnen Sekai was created named Shōjo Sekai. Also some children's books were translated to Japanese and published in Shōnen Sekai. The magazine had many features too, such as sugoroku boards and baseball cards. Shōnen Sekai was mentioned in many American books but no series were actually translated.

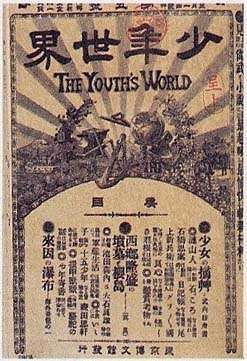

A black and white issue of Shōnen Sekai, volume 2, issue 5, from the Meiji era. Old postal stamps are also seen. | |

| Editor | Sazanami Iwaya |

|---|---|

| Categories | manga, shōnen, fiction, nonfiction, art |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Publisher | Sazanami Iwaya |

| Year founded | 1895 |

| Final issue | 1914 |

| Company | Hakubunkan |

| Country | Japan |

| Based in | Tokyo |

| Language | Japanese |

History

Japanese publisher Hakubunkan was aiming to create a large variety of magazines that would appeal to many different parts of society: Taiyō, Bungei Club, and Shōnen Sekai were the magazines created and all debuted in 1895 (the Meiji era).[1][2][3] On the cover of the first issue of Shōnen Sekai it pictured both Crown Prince Munehito, and the other Empress Jingū who was conquering Sankan (three ancient kingdoms of Korea). Inside of the issue were stories about these matters and Toyotomi Hideyoshi's raid on Korea in 1590.[4] The pioneer of modern Japanese children's media Sazanami Iwaya wrote the first modern children's story Koganemaru in 1891 and also started Shōnen Sekai in 1895.[5] Shunrō Oshikawa invented the "adventure manga" genre, with his works being published many times in both Shōnen Sekai and Shōnen Club and compiled into tankōbon format.[5] In the middle of the Sino-Japanese War Shōnen Sekai featured many stories based on war, or acts of bravery upon war.[4] After the Sino-Japanese War, Shōjo Sekai was created as a sister magazine geared towards the female audience.[6] Even before Shōnen Sekai debuted, Hakubunkan created special magazine issue that would focus on the Sino-Japanese War.[4]

Features

The Shōnen Sekai magazine had many add-ins such as sugoroku boards. The sugoroku Shōnen Sekai Kyōso Sugoroku was originally produced as a supplement to the Shōnen Sekai magazine and is currently seen at the Tsukiji Sugoroku Museum in Japan.[7] Also packs of baseball cards were featured in the magazine in a February 1915 issue of Shōnen Sekai. Players that were included into the pack were Fumio Fujimura, Makoto Kozuru, Shigeru Chiba and Hideo Fujimoto.[8] Many manga and children's literature were featured in Shōnen Sekai. An example of this was Iwaya Sazanami (the creator of Shōnen Sekai)'s Shin Hakken-den which had the concept of rewarding the good and punishing the evil a common theme to children's fiction in the 20th century. Shin Hakken-den was based on Nansō Satomi Hakkenden from the Edo period by Takizawa Bakin. Shōnen Sekai carried many stories based on war, and acts of bravery upon war[4] written by Hyōtayu Shimanuki[3] [Hyōdayu -]. In Shōnen Sekai some titles were also translated from other languages, for example: Deux ans de vacances (an obscure French novel from the 1800s) was translated to Japanese by Morita Shiken under the title Jūgo Shōnen (十五少年) and The Jungle Book was also published in Shōnen Sekai.[9][10]

Shōnen Sekai media in the English language

Shōnen Sekai was mentioned various times in many English books. In the book The New Japanese Women: Modernity, Media, and Women in Interwar Japan mentioned Shōnen Sekai in the notes to chapter 3 as one of many magazines that Hakubunkan made to relate to different parts of society.[2] Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War also mentioned Shōnen Sekai as a popular magazine of that time, with an additional mention to Shōjo Sekai, its female equivalent.[6] Issei: Japanese Immigrants in Hawaii mentioned Shōnen Sekai as just a publication of Hakubunkan.[3] In the book No Sword to Bury: Japanese Americans in Hawai'i During World War II had mention of Shimanuki Hyotayu who writes about immigration matters in Shōnen Sekai.[11] Shōnen Sekai was also mentioned in both The Similitude of Blossoms: A Critical Biography of Izumi Kyōka (1873–1939), Japanese Novelist and Playwright and Japan's Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period.[12][13]

The closest thing to an actual series published in English was The Jungle Book which was originally in the English language.[10] The Jungle Book was published in the United States by Macmillan Publishers in 1894 and is currently being published by them in London.[14]

Reception and legacy

Shōnen Sekai was one of the most popular children's magazines of its day. Many other children's magazines of that time had very low circulations and were very short lived. Shōnen Sekai was the first of its kind and ran continuously from 1895 to 1914. "Shōnen sekai educated and entertained at least two generations of Japanese children"[4]

I have not been able to obtain accurate circulation figures but Shōnen sekai’s longevity alone, compared with that of most other children’s media until the WWI years, suggests its dominance through the mid-1910s. This was certainly the official position of Hakubunkan as can be seen in Tsubotani Yoshiyoro,[15]

— Hakubunkan History, [4]

Modeled on Shōnen Sekai Choe Nam-seon founded a magazine, Shonen, in Korea in 1908.[16]

Notes

References

- "National Diet Library Newsletter". National Diet Library. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Sato, Barbara Hamill (2003). The New Japanese Woman: Modernity, Media, and Women in Interwar Japan. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-8223-3044-X. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Kimura, Yukito (1992). Issei: Japanese Immigrants in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-8248-1481-9. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Owen Griffiths. "Militarizing Japan: Patriotism, Profit, and Children's Print Media, 1894-1925". Japan Focus. Archived from the original on 8 August 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Owen Griffiths (September 2005). "A nightmare in the making: war, nation and children's media in Japan, 1891-1945" (PDF). International Institute of Asian Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Lone, Stewart (2007). Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-313-33684-3. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ""Shōnen Sekai Kyoso Sugoroku" (Boys World's Competition Sugoroku)". Sugoroku Library. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- "[Middle of magazine]". Shōnen Sekai (in Japanese). Hakubunkan. February 1950.

- "Japanese Translations in the Meiji Era". Yahoo! Japan. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- "A List of Research and Reviews Related to Children's Literature in 1998〜1999". International Institute for Children's Literature. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Odo, Franklin (2004). No Sword to Bury: Japanese Americans in Hawai'i During World War II. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 29. ISBN 1-59213-270-7. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

shonen sekai.

- Shirō Inouye, Charles (1998). The Similitude of Blossoms: A Critical Biography of Izumi Kyōka (1873-1939), Japanese Novelist and Playwright. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 80. ISBN 0-674-80816-9. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Gluck, Carol (1987). Japan's Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0-691-00812-4. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- "The Jungle Book". Macmillan Publishers. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- His name is 'Tsuboya Zenshiro (坪谷善四郎)' correctly.

- "Countries and Regions with many Translations of Japanese Children's Books". Kodomo. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

External links

- Shōnen Sekai page at National Diet Library (Pic 3) (in English)

- Shōnen Sekai page at National Diet Library (Pic 3-2) (in English)