Yushima Seidō

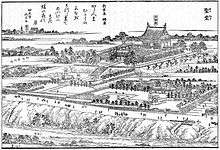

Yushima Seidō[1] (湯島聖堂, lit. 'Yushima Sacred Hall'), is a Confucian temple (聖堂) in Yushima, Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. It was established in end of the 17th century during the Genroku era of the Edo period.

Towards the later Edo period, one of the most important educational institutions of the shogunate, the Shōhei-zaka Gakumonjo (昌平坂学問所), or Shōheikō (昌平黌), was founded on its grounds.

Shōheikō

Background

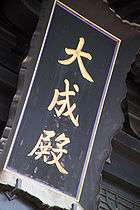

The Yushima Seidō has its origins in a private Confucian temple, the Sensei-den (先聖殿), constructed in 1630 by the neo-Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (1583–1657) in his grounds at Shinobu-ga-oka (now in Ueno Park). The fifth Tokugawa shōgun, Tsunayoshi, moved the building to its present site in 1690, where it became the Taiseiden (大成殿) of Yushima Seidō. The Hayashi school of Confucianism moved at the same time.

Under the Kansei Edict, which made neo-Confucianism the official philosophy of Japan, the Hayashi school was transformed into a state-run school under the direct control of the shogunate in 1797, the most important school of this kind in the country. The school was known as the Shōhei-zaka Gakumonjo (昌平坂学問所) or Shōheikō (昌平黌), after the supposed birthplace area of Confucius (昌平, Shōhei in Japanese). During the time of the Tokugawa shogunate, the school attracted many men of talent, but it was closed in 1871 after the Meiji Restoration. The school campus at the time covered a much larger area than the current grounds of the temple, including where the modern Tokyo Medical and Dental University stands.

The rector of Shoheikō was for all intents and purposes at the head of the educational system in Edo. The position was held by the head of the Hayashi clan.

Education at Shōheikō

The school had three kinds of students: direct trainees of the Shogunate bureaucracy (稽古人, Keikonin) , resident trainees (書生, Shosei) and free listeners (聴聞人, Chōmonjin) attending only open lessons. The Keikonin were from the Hatamoto and Gokenin families in Edo, direct vassals of the Shogunate. A small dormitory for them was available, but its capacity was limited, and most Keikonin students would commute daily from their Edo estate. A larger dormitory was available for the Shosei resident trainees, who were coming as scholarship students from all Han fiefs of the country. Besides lessons, the Shosei students lived on campus and spent a lot of time scholarly debating among themselves, naturally creating a strong alumni network spanning all over the country, which was key during the Meiji restoration[2].

An introduction by a Keikonin following by an interview by the teaching staff was needed to enroll the school. Courses were focusing on confucian teachings with in-depth studies from start to end of Chinese texts. Unsurprisingly, the Four books and Five classics were studied extensively. On top of lessons for the resident students and the Keikonin, there were open courses available to the common people everyday.

Several kinds of examinations were performed, from the Sodokuginmi (素読吟味, litt."Reading examination"), held yearly to evaluate younger trainees and whether they could continue or not their studies, to the prestigious Gakumonginmi (学問吟味, litt. "Scholar examination"), held only 19 times [3]in the whole history of the school.

Shōheikō alumni and scholars

- Saitō Chikudō

- Takasugi Shinsaku

- Akizuki Teijirō

- Kume Kunitake

- Kiyokawa Hachiro

- Matsumoto Keido

- Edayoshi Shinyo

- Mishima Choshu

Institutional history after 1871 and legacy

Since the Meiji restoration, Yushima Seidō has temporarily shared its premises with a number of different institutions, including the Ministry of Education, the Tokyo National Museum, and the forerunners of today’s Tsukuba University and Ochanomizu University (which is now in a different location but retains "Ochanomizu" in its name).

The site of the school is now occupied by the Tokyo Medical and Dental University.

The colour scheme of the original Taiseiden is believed to have been one of vermilion paint with verdigris. After being burnt down on a number of occasions, the Taiseiden was rebuilt in 1799 in the style of the Confucian temple in Mito, which used black paint. This building survived through the Meiji period and was designated a national historical site in 1922, but was burnt down in the Great Kantō earthquake of the following year. The current Taiseiden is in reinforced concrete and was designed by Itō Chūta.

Inside the compound is the world's largest statue of Confucius, donated in 1975 by the Lions Club of Taipei, Taiwan. There are also statues of the Four Sages, Yan Hui, Zengzi, Kong Ji, and Mencius.

In the 1970s, the Taiseiden was used as the location for scenes in NTV's Monkey television series.

Along with the nearby Yushima Tenman-gū, the Yushima Seidō attracts students praying for success in their examinations.

See also

- Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi) – neo-Confucianist teacher

- Fujiwara Seika – Japanese disciple of Zhu Xi

- Hayashi clan (Confucian scholars)

- Wagakukodansho, a shogunate-sanctionned education institute focused on Japanese classics and Japanese history

- Igakukan, a shogunate-sanctionned education institute focusing on traditional Chinese medecine

- Bansho Shirabesho, a late Edo period institute on the translation/study of foreign works

References

- Patricia Jane Graham (2007). Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1600-2005. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-0-8248-3191-2.

- Yoshimura, Hisao (December 2016). "朱子学の官学「昌平黌」" [Shoheiko - the bureaucrat confucian school]. Kigyoka Club. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- Hashimoto, Akihito. "江戸幕府学問吟味受験者の学習歴" [Educational background of students passing the Gakumonginmi examination]. Japan Society for the Historical Studies of Education.

Bibliography

- Brownlee, John S. (1997) Japanese historians and the national myths, 1600–1945: The Age of the Gods and Emperor Jimmu. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0644-2 Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 978-4-13-027031-1

- Brownlee, John S. (1991). Political Thought in Japanese Historical Writing: From Kojiki (712) to Tokushi Yoron (1712). Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-997-8

- Cullen, Louis .M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82155-1 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-521-52918-1 (paper)

- De Bary, William Theodore, Carol Gluck, Arthur E. Tiedemann. (2005). Sources of Japanese Tradition, Vol. 2. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12984-8 OCLC 255020415

- Kelly, Boyd. (1999). Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Vol. 1. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-33-6

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5 OCLC 48943301

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard A. B. (1956). Kyoto: The Old Capital of Japan, 794–1869. Kyoto: The Ponsonby Memorial Society. OCLC 36644

- Screech, Timon. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1720-0.

- Yamashita, Samuel Hideo. "Yamasaki Ansai and Confucian School Relations, 1650–1675" in Early Modern Japan, (Fall 2001). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

External links

![]()