Serotype

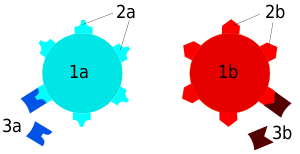

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or cells are classified together based on their cell surface antigens, allowing the epidemiologic classification of organisms to the subspecies level.[1][2][3] A group of serovars with common antigens is called a serogroup or sometimes serocomplex.

Serotyping often plays an essential role in determining species and subspecies. The Salmonella genus of bacteria, for example, has been determined to have over 2600 serotypes. Vibrio cholerae, the species of bacteria that causes cholera, has over 200 serotypes, based on cell antigens. Only two of them have been observed to produce the potent enterotoxin that results in cholera: O1 and O139.

Serotypes were discovered by the American microbiologist Rebecca Lancefield in 1933.[4]

Role in organ transplantation

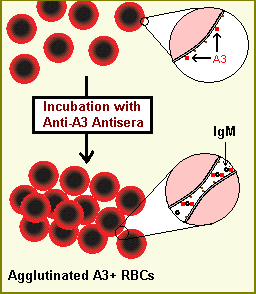

The immune system is capable of discerning a cell as being 'self' or 'non-self' according to that cell's serotype. In humans, that serotype is largely determined by human leukocyte antigen (HLA), the human version of the major histocompatibility complex. Cells determined to be non-self are usually recognized by the immune system as foreign, causing an immune response, such as hemagglutination. Serotypes differ widely between individuals; therefore, if cells from one human (or animal) are introduced into another random human, those cells are often determined to be non-self because they do not match the self-serotype. For this reason, transplants between genetically non-identical humans often induce a problematic immune response in the recipient, leading to transplant rejection. In some situations this effect can be reduced by serotyping both recipient and potential donors to determine the closest HLA match.[5]

Serotyping of Salmonella

The Kauffman–White classification scheme is the basis for naming the manifold serovars of Salmonella. To date, more than 2600 different serotypes have been identified.[6] A Salmonella serotype is determined by the unique combination of reactions of cell surface antigens. The "O" antigen is determined by the outermost portion of the Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the "H" antigen is based on the flagellar (protein) antigens.[7] There are two species of Salmonella: Salmonella bongori and Salmonella enterica. Salmonella enterica can be subdivided into six subspecies. The process to identify the serovar of the bacterium consists of finding the formula of surface antigens which represent the variations of the bacteria. The traditional method for determining the antigen formula is agglutination reactions on slides. The agglutination between the antigen and the antibody is made with a specific antisera, which reacts with the antigen to produce a mass. The antigen O is tested with a bacterial suspension from an agar plate, whereas the antigen H is tested with a bacterial suspension from a broth culture. The scheme classifies the serovar depending on its antigen formula obtained via the agglutination reactions.[8] Additional serotyping methods and alternative subtyping methodologies have been reviewed by Wattiau et al.[9]

References

- Baron EJ (1996). Baron S; et al. (eds.). Classification. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, Sherris JC, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- "Serovar". The American Heritage Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2007.

- Lancefield RC (March 1933). "A Serological Differentiation of Human and Other Groups of Hemolytic Streptococci". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 57 (4): 571–95. doi:10.1084/jem.57.4.571. PMC 2132252. PMID 19870148.

- Frohn C, Fricke L, Puchta JC, Kirchner H (February 2001). "The effect of HLA-C matching on acute renal transplant rejection". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 16 (2): 355–60. doi:10.1093/ndt/16.2.355. PMID 11158412.

- Gal-Mor O, Boyle EC, Grassl GA (2014). "Same species, different diseases: how and why typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica serovars differ". Frontiers in Microbiology. 5: 391. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00391. PMC 4120697. PMID 25136336.

- "Serotypes and the Importance of Serotyping Salmonella". CDC. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Danan C, Fremy S, Moury F, Bohnert ML, Brisabois A (2009). "Determining the serotype of isolated Salmonella strains in the veterinary sector using the rapid slide agglutination test". J. Reference. 2: 13–8.

- Wattiau P, Boland C, Bertrand S (November 2011). "Methodologies for Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica subtyping: gold standards and alternatives". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (22): 7877–85. doi:10.1128/AEM.05527-11. PMC 3209009. PMID 21856826.