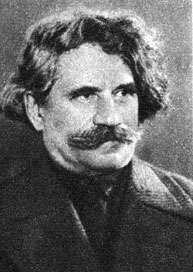

Sergei Sergeyev-Tsensky

Sergei Nikolayevich Sergeyev-Tsensky (Russian: Серге́й Николаевич Сергеев-Ценский, September 30 [O.S. September 18] 1875 – August 25, 1958) was a prolific Russian and Soviet writer and academician. According to the opinion of Sergei Sossinsky, although "Sergeyev-Tsensky does not belong to Russia's top classical authors, he might have [been] if he had not had the misfortune of living half his life under Communist rule."[1]

Sergeyev-Tsensky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 30 [O.S. September 18] 1875 Preobrazhenskoye, Rasskazovsky District, Tambov Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | August 25, 1958 (aged 82) |

| Occupation | Writer and academician |

| Genre | short stories, novels |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | Russia's Transfiguration |

Early life

Sergei Sergeyev was born on September 30 [O.S. September 18] 1875, in the village of Preobrazhenskoye, Rasskazovsky District, Tambov Governorate. His father was a teacher and a retired veteran of the Crimean War of 1853–1856.[1] At four, Sergeyev learned how to read and at five he already knew by heart many poems by Pushkin and Lermontov, as well as Krylov's fables, beginning to write his own poems at seven.[1] At this time, his family had moved to Tambov where Sergei's father received a post in the government.[1]

It was reported that Sergeyev "was fascinated by Russian translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey and read them avidly [and] at school, rewrote a scene from Boris Godunov, adding rhymes to Pushkin's blank verse, and was taken to task by the literature teacher for trying to outdo the great poet" and that when he wrote a short story at home, "his father threw into the fire, saying that prose writing was even more difficult than poetry and he was not ready for it yet."[1]

When his parents died, Sergeyev studied at a teacher-training college, graduating in 1895 and then worked as a teacher in different towns of Russia until 1904, when the Russo-Japanese War broke out and he was drafted into the army, where he spent two years.[1]

Career

He published his first works in 1898, and his first book Thoughts and Dreams in 1901. The latter contained poems with strong civic undertones.[1]

Reportedly, "after his discharge from the army, Sergeyev-Tsensky bought a plot of land in Alushta, the Crimea, and built a house on it. He would live there for the rest of his life, only leaving this beautiful corner for short trips to St. Petersburg and Moscow, and other places. He sent his stories to periodicals for publication.".[1]

In 1907, he published the novel Babayev, where he described revolutionary events in a provincial town. It was reportedly "later discovered that the story of the officer hero of the novel was actually the author's own experience in the revolution."[1]

Sergeyev had reportedly "virtually no friends among the popular writers of the day" and when, in 1906, Alexander Kuprin visited Alushta and sent a messenger to Sergeyev-Tsensky, Sergeyev "told the messenger that the letter was intended for his absent uncle." Kuprin, however, was standing nearby and made sure he spoke with Sergeyev. "Such behavior was typical of Sergeyev-Tsensky" and when staying in a famous St. Petersburg hotel known as a place where most of Russia's great writers had stayed, "Sergeyev-Tsensky put a notice on his door saying 'I'm never at home.'"[1]

During World War I, the author was again drafted into the army, but was put into the reserve because of his age. Little was heard from the writer during World War I and the following Russian Civil War with lean times forcing Sergeyev to sell off his possessions for food. A story goes that a neighbor who helped him milk a newly acquired cow soon became his wife, Khristina – a college graduate and a gifted pianist.[1]

The author turned to historical subjects in 1923, but with the communist rule, it became harder to write freely on any topic. With the rise of Maxim Gorky, however, who admired Sergeyev, things gradually improved. Reportedly, "in letter to Sergeyev-Tsensky, Gorky admitted that [although] they had differences in their attitudes to the human species [and] that Sergeyev-Tsensky did not have the respect for people that he, Gorky, felt, this did not prevent them from sharing many other basic feelings." Even with Gorky's support, however, "Sergeyev-Tsensky had difficulty adapting to Soviet reality and was, in particular, forced to rewrite some of his earlier works.".[1]

The work of his life was Russia's Transfiguration which consisted of 12 novels, 3 stories and 2 studies.[1] This work is reportedly comparable with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's Red Wheel. Both are monumental works dealing with the period before, during and after the revolution. Sergeyev-Tsensky, however, is, reportedly, "a better stylist than Solzhenitsyn, who keeps inventing non-existent Russian words [and while] both works are biased, Solzhenitsyn's bias is monarchist and self-imposed, while Sergeyev-Tsensky no doubt had to tread carefully to save his life and struggle with himself to appear pro-Soviet.".[1]

"The late 1930s were a particularly dangerous time, and to weather it Sergeyev-Tsensky had the brilliant idea to write a work about the Crimean War. His father's library included an excellent selection of books about the siege of Sevastopol, and he set to work, producing three volumes in 1936–1938, the worst years of the Great Terror. For a while it was not clear if the work would be published. The imminent war and the need to revive Russia's military past finally tipped the scales in its favor. In 1939–1940 Sevastopol Labors was published, and in 1941 the writer received the Stalin Prize instead of being sent to the Gulag. It is also probable that the fact that he lived so far from the centers of power in the Soviet Union was another factor in saving him (Sergeyev-Tsensky had been given an apartment on Tverskaya Street in Moscow, but he still spent most of his time in the Crimea). His story was not unlike that of Maximilian Voloshin, poet, artist and critic who also lived in the Crimea all his life and survived the 1930s.".[1]

"With the outbreak of World War II it became easier for many decent writers, in particular Sergeyev-Tsensky, to wholeheartedly support the Soviet regime. He wrote patriotic articles encouraging the war effort.".[1]

"After the war Sergeyev-Tsensky's position as a leading Soviet Russian writer, as he was then known, was firmly established. Nevertheless, he continued to work feverishly, produced an incredibly large number of works, including several thousand poems and fables. His 80th birthday was widely celebrated in 1955, and he also received the Lenin Prize."[1]

He died in 1958 in Leningrad, aged 82.

"It is important to note, however, that his best works were devoted to the military, whom he knew so well from his first-hand experience before the revolution. Readers who do not have a taste for military subjects find Sergeyev-Tsensky rather dull. Perhaps his best pages were devoted to the 1916 Brusilov Offensive in World War I and to General Brusilov himself. But his failing health and the difficulty of dealing with Soviet reality prevented him from completing Russia's Transfiguration. Despite the fact that Sergeyev-Tsensky may seem old-fashioned to some readers, his books continued to be published in large printings during perestroika, and he will always be read by the general reader, to say nothing of intellectuals.".[1]

Bibliography

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Sergei Sergeyev-Tsensky |

- Brusilov's Break-Through: a Novel of the First World War , translated into English by Helen Altschuler, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1945.

- Tundra (1902, The Tundra)

- Preobrazhenye zapiski (1914–40, The Transfiguration)

References

- A Riter (sic) Who Recreated Russia's Military Past. Sergei Sossinsky. Moscow News (Russia). YESTERYEAR; No. 43. November 1, 2000

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sergey Sergeyev-Tsensky. |

- Selected Bios from biography.com and encyclopedia.jrank.org

- Bibliography (in Russian)