Sentinels of the Republic

The Sentinels of the Republic was a national organization that opposed what it saw as federal encroachment on the rights of the States and of the individual.[1] Politically right-wing, the group was highly active in the 1920s and 1930s, during which it worked against child labor legislation and the New Deal.[2][3] Accusations of antisemitism and a decreasing relevance of its political agenda both served to weaken the organization, which ultimately disbanded in 1944.

| Motto | Every citizen a Sentinel: every home a sentry box! |

|---|---|

| Formation | 22 September 1922 |

| Extinction | 1944 |

| Type | NGO |

| Legal status | Association |

| Purpose | Political lobby |

| Headquarters | Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

Region served | National |

President | Louis A. Coolidge (first president) |

Main organ | Executive Committee |

Origins and formation

The Sentinels of the Republic was created as part of a surge in constitutionalism that occurred during the 1920s and 30s. During this period, historian Michael Kammen writes, constitutionalism "assumed a more central role in American culture than it ever had before," and resulted in "the efflorescence of intensely partisan organizations that promoted patriotic constitutionalism as an antidote to two dreaded nemeses, governmental centralization and socialism."[4]

In Massachusetts, on 22 September 1922 (in honor of the 200th anniversary of the birth of Samuel Adams),[5] several of these organizations, including the National Association for Constitutional Government, the Public Interest League, the League for Preservation of American Independence, the Constitution Liberty League, the Anti-Centralization Club, the Sons of the Revolution, the American Legion, the Society of the Cincinnati, the American Rights League, and the American Defense Society joined forces under a cooperative arrangement called the Sentinels of the Republic.[4] Louis A. Coolidge was chosen as the group's first president.[6]

The main purpose of the new organization was to serve as a defense against unconstitutional legislation. The Sentinels were particularly concerned with protecting the rights of the States, limiting government's interference with and regulation of business, and combating the threat of international communism.[6]

The founding principles of the Sentinels were:[7]

- "To maintain the fundamental principles of the American Constitution."

- "To oppose further Federal encroachment upon the reserved rights of the States."

- "To stop the growth of socialism."

- "To prevent the concentration of power in Washington through the multiplication of administrative bureaus under a perverted interpretation of the general welfare clause."

- "To help preserve a free republican form of Government in the United States."

The organization's motto was: Every citizen a Sentinel: every home a sentry box![8]

Leaders and notable members

The Sentinels' founding members were:[7]

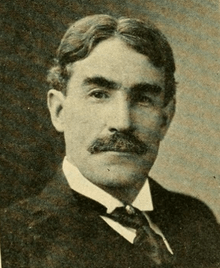

- Louis Arthur Coolidge, Treasurer of the United Shoe Machinery Corporation, former journalist and political publicist,[9] served as private secretary to U.S. Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, 1888–91

- James Jackson, Treasurer and Receiver-General of Massachusetts, former New England Chairman of the Red Cross

- Herbert Parker, former Massachusetts Attorney General

- Charles Sedgwick Rackemann, partner in the Boston law firm Rackemann, Sawyer & Brewster[10]

- Boyd B. Jones, a lawyer and former U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts[11]

- Henry F. Hurlbert, former District Attorney of Essex County, Massachusetts[12]

- Maurice S. Sherman, editor of the Hartford Courant, and later The Springfield Union[13]

- Frank F. Dresser, Massachusetts attorney

- Katharine Torbert Balch, President of the Massachusetts Women's Anti-Suffrage Association [14][15]

Founding member and first president[5]

Founding member

Founding member

Coolidge served as the Sentinels' first president from 1922 until his death in 1925.[6] He was succeeded by Bentley Wirt Warren, a Boston lawyer who had been the Democratic Party's candidate for Massachusetts' 11th Congressional District seat in 1894. Warren served from 1925 to 1927 and was succeeded by Alexander Lincoln, also a Boston lawyer, who served from 1927 to 1936.[1]

The Sentinels were heavily supported by some of the nation's wealthiest capitalists and industrialists. Raymond Pitcairn, billionaire son of PPG Industries founder, John Pitcairn, Jr., who served as the Sentinels' national chairman for several years,[2] was also the group's primary benefactor: in early 1935 he single-handedly revitalized the Sentinels with a donation of $85,000[16] (more than $1.25 million in 2008 dollars[17] ). To a group which had raised exactly $15,378.74 since 1931, this was a massive injection of capital.[16]

Other notable or prominent supporters of the Sentinels included Pitcairn's two brothers, Harold Frederick Pitcairn and Rev. Theodore Pitcairn; several powerful members of the du Pont Nemours chemical manufacturing dynasty (Pierre S. du Pont, President; Irénée du Pont, Vice Chairman; Henry du Pont, Director of the Du Pont family's Wilmington Trust; and A. B. Echols, Vice President of du Pont Nemours and Director of the Wilmington Trust); Alfred P. Sloan, the long-time president and chairman of General Motors; Atwater Kent, the wealthy radio manufacturer; former Pennsylvania Senator George Wharton Pepper; Edward T. Stotesbury, a prominent investment banker and partner of J.P. Morgan & Co. and Drexel & Co.; Horatio Lloyd, also a partner of J.P. Morgan & Co.; J. Howard Pew, the President of Sun Oil; and Bernard Kroger, founder of the Kroger chain of supermarkets.[18][19]

The Sentinels' chief officers in 1933 included:[20]

- Alexander Lincoln, President

- Frank L. Peckham, Vice-president

- William H. Coolidge, Treasurer

- John Balch, Secretary

- Thomas F. Cadwalader, Chairman of the Executive Committee

- H. G. Torbert, Executive Secretary

- Raymond Pitcairn, National Chairman

Activities and accomplishments

The Sentinels' primary activities consisted of organized opposition to expansions of the federal government, which they saw as unconstitutional encroachment on the rights of the States and of the individual.[1] Key targets included the creation of the Department of Education, the New Deal,[21] and child labor legislation.[2]

In 1924-1925 the Sentinels garnered national attention when, under the leadership of Louis A. Coolidge, they successfully swayed Massachusetts opinion against the Child Labor Act. They persuaded key Massachusetts constituents to oppose the Child Labor Act by convincing them that it had Bolshevistic origins, and that it would lead to extreme consequences; e.g. denying a teenager of the right to help his widowed mother support his siblings, or even to assist with household and farm chores. The Sentinels also claimed that the proponents of the Child Labor Act wanted to remove children from the influence of their families and the authority of their parents.[6]

Following Coolidge's death in 1925, Bentley Wirt Warren became the Sentinels' second president. Under Warren, the Sentinels continued their efforts to oppose the Sheppard–Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act of 1921 and the creation of a federal office of education. By 1927, in good part due to a flood of speakers, pamphlets, letters, and telegrams from the Sentinels, the latter was defeated.[6]

In 1926, in a fund-raising pamphlet entitled "To Arms! To Arms!", the organization boasted that it had "card-indexed more than 2000 radical propagandists making it comparatively easy to check their movements and counteract their activities."[18]

Alexander Lincoln succeeded Warren as president, and it was during his term that the Sentinels achieved their greatest prominence. During the mid-1930s, anti-New-Deal sentiment in the business community led to a substantial increase the Sentinels' standing and financial support.[6]

The Sentinels held annual meetings during this period, at each of which they adopted a "program of policies" which were then disseminated in pamphlet form to stir public opinion. They also gave radio addresses, including two series of weekly addresses aired by the National Broadcasting Company, one in 1931 and the other in 1933–1934. They also held special meetings with "keynote" addresses.[6]

In 1934, under the coordination of national chairman Raymond Pitcairn, the Sentinels conducted a large-scale campaign against a proposed tax law that would have required publication of personal financial data, including an individual's gross income. They distributed hundreds of thousands of protest stickers and form letters urging people to demand that Congress repeal what they described as an "outrageous invasion of privacy." The protest was successful: after receiving thousands of letters and telegrams opposing the legislation, Congress backed down.[2]

Accusations of antisemitism

The Sentinels faced charges of antisemitism in the media and in history books. George Seldes, an influential muckracking journalist of the 1940s, described the Sentinels as "the anti-Semitic enemy of child labor laws"[19] and "the anti-Semitic wing of the first really important American Fascist movement."[19] The historian Jules Archer writes that Sentinel members labeled Roosevelt's New Deal as "Jewish Communism".[22]

Substantiating these allegations, the Black Commission, a 1936 U.S. Senate investigation into lobbying, discovered instances of antisemitic language and attitudes within the Sentinels. Specifically, the commission uncovered a written correspondence between Sentinel member Cleveland Runyon and Alexander Lincoln, the organization's president, in which the latter wrote that the "Jewish threat" to the United States was a "real one" and added that "I am doing what I can as an officer of the Sentinels."[23] The former responded that the "old-line Americans of $1200 a year want a Hitler."[23][24]

Following the resulting charges of antisemitism, Lincoln later denounced all forms of autocratic government, "whether they be communism, bolshevism, fascism, or Hitlerism."[25] The commander-in-chief of the Jewish War Veterans wrote to Lincoln that, following its own investigation, his organization had concluded that Lincoln did not "entertain any antipathy against the Jewish people or any racial minority."[25] However, these statements failed to erase the damage done to the reputation of the American Liberty League (the parent organization of the Sentinels) by the findings of the Black investigation.[25] While the incident itself may have been a small part of the history of the Sentinels, it was the organization's largest source of press coverage.[21]

Dissolution

By the 1940s, with their political objectives increasingly obsolete, the Sentinels had lost most of their support base, funds and influence.[6][21] Finally, in 1944, they disbanded.[21]

The organization donated the remainder of its funds to Williams College for the purpose of endowing the Sentinels of the Republic Advanced Study Prize, a yearly award for the best student essay on the U.S. Constitution.[21] The Sentinels also donated a collection of primary documents (brochures, newsletters, minutes) to the college's archives, where they currently reside, for the purpose of aiding students in preparing their essays.[6] The decision to endow Williams was presumably influenced by the fact that at the time the decision was taken to disband, former Sentinels president and trustee Bentley W. Warren was serving on Williams' Board of Trustees.[6]

References

- "Lincoln, Alexander, 1873- . Papers, 1919-1940: A Finding Aid". Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. Retrieved 2 Nov 2008.

- Sanders, Richard (March 2004). "Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism: Pitcairn family". Press for Conversion! Magazine (# 53).

- Bowes, Julia (2019). ""Every Citizen a Sentinel! Every Home a Sentry Box!" The Sentinels of the Republic and the Gendered Origins of Free-Market Conservatism". Modern American History. 2 (3): 269–297. doi:10.1017/mah.2019.34. ISSN 2515-0456.

- Kammen, Michael G. (1986). A machine that would go of itself: the Constitution in American culture. Transaction Publishers. pp. 219, 225. ISBN 9781412827768.

- "Mustering Sentinels of the Republic!" (PDF). National Magazine (W. W. Potter Company of Boston, MA). Oct 1922. Retrieved 9 Feb 2009.

- "Sentinels of the Republic Records, 1922-1944". Williams College Archives and Special Collections. Retrieved 2 Nov 2008.

- Special to the New York Times (20 Aug 1922). "Sentinels of the Republic; New Extra-Political Organization Is Incorporated in Boston". New York Times. p. 26. Retrieved 20 Nov 2008.

- "Sentinels of the Republic Letter to Alice Robertson" (PDF). Alice Robertson Collection: Series II: Correspondence. McFarlin Library Digital Collections, University of Tulsa. 1923. Retrieved 9 Feb 2009.

- Jones, R. Victor (21 Nov 2001). "Gordon McKay". R. Victor Jones. Retrieved 16 Feb 2010.

- "Rackemann, Sawyer & Brewster: History". Rackemann, Sawyer & Brewster. Retrieved 16 Feb 2010.

- Bacon, Edwin M. (1916). The Book of Boston. Boston, MA: The Pilgrim Press. pp. 434. ISBN 0-205-13594-3.

boyd b jones mckinley.

- Hobbs, Clarence W. (1886). Lynn and Surroundings. Lynn, MA: Lewis & Winship. pp. 146.

henry f hurlburt.

- "Sherman Speaks at Tech banquet" (PDF). The Tech. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. XLV (78): 1. 22 Jan 1926. Retrieved 16 Feb 2010.

- Balch, Katharine T. (15 Nov 1921). "To the Readers of The Woman Patriot". The Woman Patriot. p. 4. Retrieved 16 Feb 2010.

- Massachusetts Women with an Introduction by Ernest Bernbaum, Ph.D. (1916). 'Who the Massachusetts Anti-Suffragists Are' by Katharine Torbert Balch, in Anti-Suffrage Essays. Boston: The Forum Publications of Boston. pp. 21–23.

- Lichtman, Allan J. (2008). White Protestant Nation: The Rise of the American Conservative Movement. New York, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-87113-984-9.

Sentinels of the Republic president.

- "The Inflation Calculator". Retrieved 12 Dec 2008.

- Editor (10 May 1936). "Fascist Organization Started in the United States in 1922". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 1. Retrieved 18 Feb 2010.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Seldes, George (1947). One thousand Americans: The Real Rulers of the U.S.A. New York: Boni & Gaer. pp. 154, 183.

- "Senate record, 1933" (PDF). Social Security Administration. Retrieved 12 Dec 2008.

- "Sentinels of the Republic". Willipedia, the WSO wiki. 28 Nov 2006. Retrieved 20 Nov 2008.

- Archer, Jules (2007) [1973]. The Plot to Seize the White House. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. (orig. Hawthorne Books). p. 31. ISBN 978-1-60239-036-2.

- Special to the New York Times (18 Apr 1936). "Says Smith Spoke For Liberty League to Remove Taint". New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 20 Nov 2008.

- Colby, Gerald (Sep 1984). ""Decade of Despair"". Du Pont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain. Secaucus: L. Stuart. ISBN 978-0-8184-0352-1.

- Wolfskill, George (1962). The Revolt of the Conservatives: A History of the American Liberty League, 1934-1940. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 233.