Seleucid Dynastic Wars

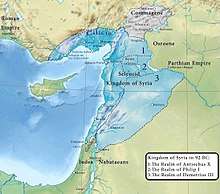

The Seleucid Dynastic Wars were a series of wars of succession that were fought between competing branches of the Seleucid royal household for control of the Seleucid Empire. Beginning as a by-product of several succession crises that arose from the reigns of Seleucus IV Philopator and his brother Antiochus IV Epiphanes in the 170s and 160s, the wars typified the final years of the empire and were an important cause of its decline as a major power in the Near East and Hellenistic world. The last war ended with the collapse of the kingdom and its annexation by the Romans in 63 BC.

| Seleucid Dynastic Wars | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coin of Demetrius II, one of the principal figures in the dynastic wars of the later Seleucid Empire | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| Line of Seleucus IV 157–63 BC | Line of Antiochus IV 157–123 BC | Line of Antiochus VII 114–63 BC | ||||||

Background

The civil wars that characterized the later years of the Seleucid Kingdom had their origins in the defeat of Antiochus III the Great in the Roman–Seleucid War, under which the peace terms ensured that a representative of the Seleucid royal family was held in Rome as a hostage. Initially the future Antiochus IV Epiphanes was held hostage, but with the succession of his brother, Seleucus IV Philopater, in 187 and his apparent breaking of the Treaty of Apamea with Rome, Seleucus was forced to recall Antiochus to Syria and instead replace him with his son, the future Demetrius I Soter in 178 BC.

Rule of Antiochus V

When Seleucus was murdered by his minister Heliodorus in a power bid in 175, the legitimate heir was held as a hostage in Rome. With Demetrius so far from home and unable to claim the kingdom, his uncle Antiochus left Athens, where he had been residing for several years, and claimed the kingship for himself. He ruled the empire from 175 until his death whilst on a campaign in the east in 164 BC. A strong and energetic ruler Antiochus left an heir, but he was too young to claim the throne. Before Antiochus had set out on his eastern campaign, he had placed Lysias as his regent in the west and to take charge of his son, Antiochus V Eupator. Lysias and his colleagues fought off a rival to their control of the regency, the former king's ‘Friend’ Philip who had travelled east with him, and attempted to exert control over the Jews led by Judas Maccabeus.[1] Meanwhile, Demetrius in Rome yearned to return to the kingdom, but to Rome they saw the weak rule of the supposedly corrupt regency council and its boy-king as preferable to a strong-willed and energetic-minded ruler who may try to exert Seleucid control once more in the east.[2]

Accession of Demetrius I

Eventually Demetrius was able to escape from Rome and return to Syria via Tripolis, where he quickly established himself and was made king with little fighting – the army and people flocked to support him. His cousin, the boy Antiochus V, and his regent, Lysias, were put to death by order of Demetrius before they could be physically brought to him from Antioch.[3] As a ruler, however, he proved a disappointment. He disliked the Syrians as a people and became distant from his subjects, causing much resentment. Besides this, he attempted to reassert the Seleucid Empire once more as a major power and initiated several disastrous foreign adventures, which would ultimately lead his neighbouring rulers wishing to destabilise or even eliminate Demetrius.[4] The rulers of Egypt, Cappadocia and Pergamon, among others, such as the former finance minister of Antiochus IV, Heracleides, conspired to dispose of Demetrius.

Pretender Alexander Balas

Heracleides put forward a potential candidate for the Seleucid throne, the supposed son of Antiochus IV, and brother of Antiochus V, Alexander Balas. Whether or not he was truly the son of Antiochus IV Epiphanes is uncertain, but this did not matter to the ruler of Pergamon, either Eumenes II or his heir Attalus II Philadelphus depending on the sources, who initially interviewed him. Having been recognized by the conspiring kings as the rightful heir to the Seleucid throne, Alexander was sent to the hills of Cilicia under the watchful eye of the Cilician chieftain Zenophanes.[5]

Building up his reputation and gathering forces, Alexander was quickly sent with Heracleides to Rome, where they accepted him as the true king and gave their vocal support, albeit without any real material assistance.[6] Returning to the east Alexander Balas, his ships, mercenaries and auxiliaries provided by Ptolemy VI Philometor and from Pergamon, began his insurrection against Demetrius Soter. In 152 BC, he landed at Ptolemais to make his bid for power. Ptolemais was chosen, most likely, due to its proximity to Ptolemaic Egypt and the support that would come from Ptolemy VI.[7]

Alexander Balas and the Ptolemaic ascendency 152–145 BC

| The Wars of Alexander Balas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Seleucid Dynastic Wars | |||||||

Alexander Balas was supposedly an illegitimate son of Antiochus IV and was supported by the rulers of Egypt, Pergamon and Cappadocia. He fought against Demetrius Soter and his son Demetrius Nicator, ultimately being defeated and assassinated. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by: Ptolemaic Kingdom (145 BC) |

Supported by: Ptolemaic Kingdom (157–145 BC) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

With Alexander established in the south at Ptolemais, Demetrius attempted to persuade the Jews under Jonathan Apphus to serve the Seleucid throne and help defeat him. But Alexander also sent word to Jonathan, promised him more powers and appointed him High Priest of the Jews.[8]

Alexander versus Demetrius I

At this point, Demetrius was threatened from the north by Pergamon and the pro-Alexander forces under Zenophanes in Cilicia and from the south by Alexander himself and Ptolemy VI. Nevertheless, at this stage both armies seemed to be generally the same size, leading to a stalemate. However, in 151/0 Alexander began to extend his control up the Phoenician coast, taking Tyre, Sidon and Berytus – perhaps assisted by naval support provided from the Seleucid fleet based at Ptolemais and from Ptolemy. By this time, Alexander was militarily strong enough to march north to confront Demetrius properly, reinforced by further mercenaries and defectors from Demetrius.[9] Alexander’s march north in 150 BC lead to two confrontations with the army of Demetrius, the first being a victory for Demetrius. However a decisive victory for Alexander was gained outside Antioch in 150. Demetrius’s left flank pushed aside Alexander’s right, even advancing far enough to loot the enemy camp, but on his right Demetrius was beaten by Alexander’s left. Demetrius, fighting on the right flank was caught in boggy terrain and unseated from his horse. He continued to fight on foot but was surrounded and killed by a great number of enemy troops.[10]

Demetrius' sons strike back

With Demetrius dead, Alexander was now undisputed king of the Seleucid kingdom. But he faced one major problem – the sons of Demetrius. Though young, both Demetrius II Nicator and Antiochus VII Sidetes were sent abroad by their father, as he feared that they would be put to death as rival claimants, and to hopefully be a rallying point for the loyalists to the legitimate branch of the royal family. Demetrius was sent to Crete, to raise a mercenary army from Crete itself and the Greek islands under the captain Lasthenes. Within two years a sufficient force had been raised to begin their campaign.[11] By 148/147 BC Lasthenes and Demetrius were ready to begin their attempt to reclaim the kingdom. Demetrius was still very young, aged at about fourteen years, so in reality the campaign and leadership was provided by Lasthenes. They landed in Cilicia, which would provide a good line of retreat should the expedition turn out badly, and the younger brother of Demetrius, Antiochus, was sent to the city of Side in Pamphylia – perhaps to provide the Demetrian forces with another claimant should Demetrius be caught or killed.[12]

Alexander, based primarily in Ptolemais, no doubt due to its close proximity to his benefactor and ally Ptolemy VI Philometor, moved north to Antioch to counter the Demetrian invasion, but found the population discontented and irate. Alexander, though initially popular, had proven himself incompetent at the ruling of a kingdom and spent a considerable amount of his reign in pursuit of pleasure.[13] As soon as Alexander turned his back to counter the invasion in the north, his governor in Palestine, Apollonius Taos, defected immediately to Demetrius – the Hellenized Philistine cities giving their support. Alexander appealed to his Judean ally, Jonathan Apphus, to intervene against Apollonius, which he did by mustering his army, besieging Joppa and then decisively defeating Apollonius near Azotus. Jonathan later sacked the city and the temple of Dagon. On hearing this, Alexander rewarded Jonathan with dominion over the city of Accaron (Ekron)[14]

Despite being in stalemate with Demetrius and having an obvious edge with the addition of Judean forces, Alexander was reluctant to bring them north – the Judeans had a bad reputation for their anti-Hellenism, especially their expelling of non-Jews etc. Such forces would prove a liability for Alexander and so he kept Jonathan in the south, where he could counter the pro-Demetrius strongholds in Palestine – Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod and Ptolemais.[15] Both armies at this point were evenly matched, causing a stalemate. The Demetrian army under Lasthenes was professional and reliable, being composed mainly of mercenaries, but was relatively small and had the ever looming issue of their pay. A large army was not affordable for the Demetrian insurgents. In comparison Alexander had to gather troops from considerable distances away, but had to ensure that he left enough men in the peripheral provinces to deter foreign invasions from enemies such as the Parthians or other eastern kingdoms. In fact a possible rebellion or Parthian excursion was defeated decisively by the viceroy of the Upper Satrapies, Kleomenes, in the summer of 148, his victory being commemorated by a triumphal statue of Herakles erected in the Bisitun Pass.[16]

Ptolemaic intervention

It was due to this stalemate that Alexander eventually convinced his Egyptian ally and father-in-law, Ptolemy Philometor, to intervene decisively in 147 BC. Ptolemy, seeing an opportunity to keep his influence in Syria and perhaps reclaim Coele-Syria as a reward, marched north occupying much of the Palestinian and Phoenician coastline, placing garrisons as he advanced. He was met by Jonathan and his Judean army at Ptolemais, and both armies marched up to the Eleutheros River, where Ptolemy turned Jonathan back southward. Ptolemy then advanced to Seleucia. The Ptolemaic army was itself professional, large and experienced – a possibly decisive factor in the war at this point.[17]

But no sooner had Ptolemy arrived in northern Syria, than he broke with Alexander over a supposed attempt on his life back in the south. Ptolemy blamed Alexander’s chief minister Ammonius and demanded that Alexander hand him over for punishment, which Alexander refused. Ptolemy, who had been in possession of his daughter Cleopatra Thea from Ptolemais onward, declared their marriage void and offered her to Demetrius. Denied support and with a large enemy force nearby, Alexander fled Antioch and moved north to raise troops. Demetrius and Ptolemy were now allies, and it seemed that the price for Ptolemy’s intervention was the reintegration of Coele-Syria and Palestine back into Egypt.[18]

The governors of Antioch, Hierax and Diodotus Tryphon, despairing of Alexander and fearing Demetrius offered the Seleucid crown to Ptolemy VI Philometor and convinced the populace to push for this outcome too. Ptolemy certainly considered the prospect and took at least a month to decide, but after careful consideration, especially on the opinion of Rome to this, he declined. In turn he convinced them to accept Demetrius as their rightful king, stating that he would rule benevolently and not seek revenge against those who had overthrown his father in 150 BC.[19]

In the summer of 145 BC, with enough forces raised in the north of the kingdom, which Josephus called a ‘numerous and great army’, Alexander felt confident enough to march south to confront Demetrius and Ptolemy. Crossing the Amanus into the plain of Syria, Alexander began to plunder the countryside surrounding Antioch.[20] The armies of the three kings finally came to battle near Antioch at the River Oenoparos. Demetrius and Ptolemy routed Alexander who escaped, but Ptolemy was thrown from his horse, fracturing his skull. Alexander meanwhile had fled with five hundred picked men to Abae, in what Diodorus calls, Arabia to seek refuge with an allied Arab prince. However two of Alexander’s officers, Heliades and Casius, negotiated their own safety and volunteered to assassinate Alexander, which they did. Alexander’s head was brought to Ptolemy, who had briefly regained consciousness following his fracture. Some days later he died at the hands of his surgeons who were operating on him.[21]

Aftermath

With Alexander murdered and Ptolemy dead, Demetrius was undisputed ruler of the Seleucid kingdom. However, Demetrius faced major problems with his victory – a costly victory in terms of manpower, the loyalty of his newly won kingdom, his dependence on the mercenaries, especially the Cretans under Lasthenes, to keep him in control and the Ptolemaic forces still occupying much of the Syrian and Phoenician coast. Lasthenes, with his new-found power, was made in effect minister of finance and given absolute rule of Antioch, which would have dire consequences for the young king Demetrius.[22]

The Ptolemaic garrisons disintegrated and chose to retreat back to Egypt, Demetrius having ordered them to leave and compelling the local populations to expel them with force should need be. Demetrius was now in full control of the kingdom but his rule would ultimately be troubled by civil strife and further civil war.

Insurrection of Antiochus Dionysus and Diodotus Tryphon 145–138 BC

| War of Antiochus VI and Tryphon | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Seleucid Dynastic Wars | ||||||||

Antiochus VI was the son of Alexander Balas. His regent was Diodotus Tryphon, who at the boys death proclaimed himself king and ruled parts of Syria until his defeat at the hands of Antiochus VII Sidetes. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| Legitimate Faction (145–138 BC) | Alexandrian Faction (145–142 BC) | Tryphon Faction (142–138 BC) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

Trouble in Antioch

Alexander Balas, much like Demetrius I Soter before him, feared for the safety of his heirs in the event of an enemy victory. According to Diodorus, Alexander therefore sent his son Antiochus to an allied Arab chieftain, named Iamblichus, for safety and as a rallying point for forces loyal to him, should he fall. It was the former Alexandrian commander and governor of Antioch, Diodotus, who would later convince the Arab leader to hand over custody of the child to him after having started a rebellion in Apamea.[23]

In the meantime, Demetrius II Nicator was still young and reliant on his mercenary forces to maintain control. However his rule, feeling the same disdain and contempt for the Syrian people that his father felt, was one epitomised by terror and repression. A great purge of the supporters of Alexander Balas was followed by forceful collection of wealth by his mercenary forces, no doubt to pay their wages for the war they had successfully concluded.[24] His mercenary commander and chief minister Lasthenes convinced Demetrius to discharge the standing garrison of Antioch, and perhaps the garrisons of other cities, and reduce the pay of the militia. The standing army in Syria was, due to the recent events, deemed unreliable by Demetrius – many had supported, no doubt, Alexander Balas.[25] This made Demetrius even more unpopular and caused great degrees of civil unrest and even rioting in Antioch. The Cretan mercenaries, reinforced by Jewish troops sent by Jonathan Apphus, who was now allied to Demetrius at the death of Alexander Balas, put the rebellion down brutally. A grand fire broke out destroying much of the city of Antioch.[26]

Diodotus' rebellion

With the kingdom greatly discontented and ripe for insurrection, Diodotus made his move against Demetrius II in early 144. Starting his rebellion in his home province of Apamea, he gathered supporters, no doubt gaining great strength from the actual city of Apamea. Apamea, which was once named Pella, was the major military centre of the kingdom. It was the seat of the royal stud, housed the elephant corps, the War Office (Stratiotikon Logisterion) and the military training school. The city and its neighbouring settlements at, for example, Larissa, had a Greco-Macedonian population larger than Antioch and Cyrrhestica. In fact Larissa was the headquarters of the ‘First Agema of the Cavalry’, an elite cavalry unit of the Seleucid army, and was previously loyal to Alexander Balas.[27] Diodotus could rely on these regions and on the dismissed troops from Antioch and elsewhere, enlisting them as new soldiers. It was probable that many of the troops of the standing army intended to desert from Demetrius anyway, but now they had a focal point – Diodotus.[28]

Not soon after declaring his rebellion, Diodotus proclaimed the child of Alexander Balas as King Antiochus VI Dionysus. Antiochus was only a child, and therefore a useful tool to control the loyalty of the disaffected Seleucid subjects. Diodotus established himself soon thereafter at Chalcis, to the east of Antioch. The rebellion was now at the point of open war, and the majority of the fighting was conducted in northern Syria for control of the major cities. In 143, Diodotus assaulted and captured Antioch, pushing Demetrius to the coastal city of Seleucia. At their highest point, in about 143/142 BC, Diodotus and Antiochus VI occupied most of inner Syria (including Antioch, Apamea, Chalcis and Larissa); Tarsus, Mallus and Coracesium in Cilicia; and the southern coastal cities of Aradus, Orthosia, Byblos, Berytus, Ptolemais and Dora. In comparison, Demetrius controlled the rest of the Syrian and Phoenician coasts including Seleucia, Laodicea, Tyre and Sidon as well as the majority of Cilicia.[29] The periphery of the empire was generally loyal to Demetrius, but in some parts, like Babylonia, it wavered for some time at one point supporting Antiochus, but ultimately reverted to support for Demetrius.

War in Palestine

It was at this point that the importance of the semi-independent states, like Judea, became apparent. Jonathan Apphus, as a former friend of Alexander Balas, and despite his brief alliance with Demetrius, eventually joined Diodotus to battle against Demetrius II. Jonathan was given leave by Diodotus and Antiochus to raise an army and campaign against the generals of Demetrius in Palestine. Simon Thassi, Jonathan’s brother, was made Strategos, or governor, of the territories from the Egyptian border up to Tyre, though most of the non-Jewish Palestinian cities remained loyal to Demetrius. Gaza which had initially declared for Demetrius at some point defected, but ultimately joined neither side, attempting to exert a degree of neutrality in the civil war. Meanwhile Jonathan campaigned throughout the southern regions of the Seleucid kingdom. Ascalon submitted to him and he eventually besieged Gaza, it was at this point that Demetrius sent an expedition southward to counter him.[30] The Demetrian army engaged Jonathan at Tell Hazor, south of the sea of Galilee. Jonathan fell into a trap, but his army fled before later rallying southwards. Despite this victory, the Demetrian generals did not pursue him. In the meantime, Simon, with his own force forced the settlement of Beth Zur to surrender to him and later occupied Joppa. At this point the Demetrian army was recalled northward.

Diodotus claims kingship

By this point, in the middle of 142 BC, Antiochus VI died. It is said that Diodotus had the boy killed to fulfil his ambitions of becoming king himself and it is apparent that many of the ancient historians lay the blame of the boy’s death in surgery at the feet of Diodotus.[31] Despite this Diodotus put himself forward as king under the new regal name of Tryphon, meaning ‘the magnificent’, he added as his official epiphet ‘Autokrator’, a term that linked him back to the days of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great – it was this term that they were given by the Greek cities at commander of their armies. It was either at Antioch or Apamea that he was ‘elected’ by the Greco-Macedonian soldiery as king, and to show his links to the soldiery his emblem shown on coins was that of a helmet, a composite of the popular Boeotian and Konos helmet styles.[32]

The boldness of the Jewish offensives against the loyalists of Demetrius led Diodotus to fear an ever-increasing Jewish independence, and as such began to plot against Jonathan – this being whilst Antiochus VI was still alive. Luring Jonathan to Ptolemais with a small guard, Diodotus kidnapped him and unsuccessfully held him for ransom. He eventually had Jonathan executed and initiated an invasion of Judea, which failed due to either weather conditions or Jewish garrisons blocking the suitable pathways into Judea.[33]

In the same year an army of Tryphon’s routed a pro-Demetrius force under Sarpedon in between Ptolemais and Tyre, but as they were marching along the coast in pursuit, a great tidal wave wiped out the army, according to Athenaeus.[34]

Demetrius, meanwhile, had journeyed east to combat the encroachment of the Parthians, but in 139 BC was captured in Parthia. With the detested Demetrius gone, his brother, Antiochus VII Sidetes, left his home in Rhodes and married the wife of Demetrius, Cleopatra Thea, further legitimizing his position. Tryphon’s support began to deteriorate with Antiochus now the leader of the Seleucid dynastic faction in the empire.

Antiochus successfully pushed back Tryphon’s forces and besieged him in the fortress-city of Dor on the coast. Tryphon escaped by sea to Orthosia and made his way to his home-region of Apamea, where, being chased by Antiochus, he was either put to death or committed suicide.[35]

Diodotus Tryphon was unique in the history of the Seleucid empire to be the only major rebel to actively claim the throne for the whole kingdom, as opposed to the rebels Molon and Timarchus who had launched regional bids for power and had not desired to rule the whole kingdom. In addition, Tryphon’s rebellion was one of the longest lasting – beginning in 145 and ending with his death in 138 BC.

Alexander Zabinas 128–123 BC

| War of Alexander Zabinas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Seleucid Dynastic Wars | |||||||

Alexander Zabinas was put forward as a candidate for the Seleucid throne by the Ptolemaic king Ptolemy VIII to disrupt Demetrius II's plans to support his enemies in a civil war he was conducting against his niece, Cleopatra III of Egypt. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Legitimate Faction |

Usurper Faction Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Zabinas was a false Seleucid who claimed to be an adoptive son of Antiochus VII Sidetes, but in fact seems to have been the son of an Egyptian merchant named Protarchus. Antioch, Apamea, and several other cities, disgusted with the tyranny of Demetrius, acknowledged the authority of Alexander. He was used as a pawn by the Egyptian king Ptolemy VIII Physcon, who introduced Zabinas as a means of getting to the legitimate Seleucid king Demetrius II, who supported his sister Cleopatra II against him in the complicated dynastic feuds of the latter Hellenistic dynasties.[36]

Zabinas managed to defeat Demetrius II, who fled to Tyre and was killed there, and thereafter ruled parts of Syria (128–123 BC), but soon he ran out of Egyptian support and was in turn defeated by Demetrius' son Antiochus VIII Grypus.

Zabinas fled to the Seleucid capital Antiochia, where he plundered several temples. He is said to have joked about melting down a statuette of the goddess of victory Nike which was held in the hand of a Zeus statue, saying "Zeus has given me Victory". Enraged by his impiety the Antiochenes cast Zabinas out of the city. He soon fell into the hands of robbers, who delivered him up to Antiochus, by whom he was put to death, in 122 BC.

North against South 114–75 BC

| The War between Grypus and Cyzicenus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Seleucid Dynastic Wars | |||||||

Coin of Antiochus IX, who in 114 BC launched his bid for the Seleucid throne against his cousin/half-brother Antiochus VIII. A son of Antiochus VII Sidetes, he survived the death of his half-brother to rule the kingdom, only to be killed by Seleucus VI, a son of Grypus, not long afterwards. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Northern Faction | Southern Faction | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| The War of the Brothers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Seleucid Dynastic Wars | ||||||||

Coin of Demetrius III, a son of Antiochus VIII Grypus, he held Damascus having been placed there by Ptolemy IX Lathyros and fought against his brothers in the north before being taken prisoner by the Parthians, who were allied to his brother Philip I. He died in captivity, succeeded by his brother Antiochus XII. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Northern Faction (Line of Grypus) Supported by:

| Line of Cyzicenus |

Damascus Faction (Line of Grypus) Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

| Seleucus VI Epiphanes † Antiochus XI Epiphanes † Philip I Philadelphus | Antiochus X Eusebes † Antiochus XIII Asiaticus |

Demetrius III Eucaerus | ||||||

The final years 75–63 BC

Bibliography

Ancient sources

- Appian, The Syrian Wars

- Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History

- Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews

- Polybius, The Histories

- Livy, Periochae

Modern sources

- A. Bellinger, "The End of the Seleucids", in 'Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences', Volume 38, (1949)

- E. Bevan, ‘The House of Seleucus’, Vol.II (1902)

- E. Bevan, ‘The House of Ptolemy’ (1927)

- B. Bar-Kochva, ‘The Seleucid Army' (1976)

- J. Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’ (2013)

- C. Habicht, "The Seleucids and their Rivals" in 'The Cambridge Ancient History', Vol.8 (1989)

- O. Hoover, "A Revised Chronology for the Late Seleucids at Antioch (121/0-64 BC)", in 'Historia' 65/3 (2007)

- O. Hoover, A. Houghton & P. Vesely, "The Silver Mint of Damascus under Demetrius III and Antiochus XII (97/6 BC -83/2 BC)" in AJN Second Series 20 (2008)

- A. Houghton, "The Struggle for Seleucid Succession, 94-92 BC: A new tetradrachm of Antiochus XI and Philip I of Antioch", Schweizenische Numismatische Rundschau, 77 (1998)

- F. Mittag, “Blood and Money. On the loyalty of the Seleucid Army”, in 'Electrum', Vol.14 (2008)

References

- Josephus AJ 12.386

- Polybius 31.11.11

- Appian Syr. 47a-b; Josephus AJ 12.390

- Polybius 33.5.1-4; Justin 35.1.1-4

- Diodorus 31.32a

- Polybius 33.15.1-2;33.18.1-14

- Josephus AJ 13.35-37; John D. Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.17-19

- Josephus AJ 13.43-46

- John D. Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.20-21

- Josephus AJ 13.58; John D. Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.22

- Josephus AJ 13.86; Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.218

- Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.78

- Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.213, p.218

- Josephus AJ 13.88, 13.91-102; Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.79

- Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.79

- Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.80

- Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.219

- Josephus AJ 13.106-111; Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.83; Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.220

- Diodorus 32.9c; Josephus AJ 13.113-116; Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.84

- Josephus AJ 13.116; Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.221

- Diodorus 32. 9d, 10; Bevan, ‘The House of Ptolemy’, p.305

- Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.86

- Diodorus 33.4

- Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.224

- Mittag, “Blood and Money. On the loyalty of the Seleucid Army”, p.51-52

- Diodorus 33.4; Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.224-225; Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.142-43

- Bar-Kochva, ‘The Seleucid Army’, p.28-29,p.70

- Mittag, “Blood and Money. On the loyalty of the Seleucid Army”, p.52

- Strabo 16b.10; Habicht, ‘The Seleucids and their Rivals’, in “The Cambridge Ancient History”, Vol.8, p.366; Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’, p.145-147

- Josephus AJ 13.148-154; Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’,p.150

- Diodorus 33.28; Livy Periochae 55.11; Grainger, ‘Rome, Parthia, India’,p.152

- Bevan, ‘House of Seleucus’, Vol.II, p.231

- 1 Maccabees 12.39-53; Josephus AJ 13.203-218

- Athenaeus 8.333

- Josephus AJ 13.223; 1 Maccabees 15.10-38; Strabo 14.5.2

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Alexander Zabinas". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 127–128.