Sikandar Bagh

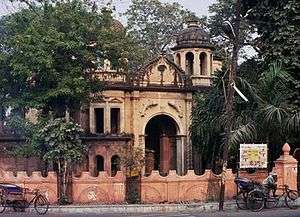

Sikandar Bagh (Hindi: सिकन्दर बाग़, Urdu: سِکندر باغ), formerly known by the British as Sikunder/Sikandra/Secundra Bagh, is a villa and garden enclosed by a fortified wall, with loopholes, gateway and corner bastions, approx. 150 yards square, c. 4.5 acres (1.8 ha), located in the city of Lucknow, Oudh, Uttar Pradesh, India. It was built by the last Nawab of Oudh, Wajid Ali Shah (1822–1887), as a summer residence. The name of the villa signifies '"Garden of Sikandar", perhaps after Alexander the Great,[2] whose name lives on in this form in these parts (compare Alexandria, Egypt, in Arabic الإسكندرية Al-Iskandariya), or perhaps after Sikandar Mahal Begum, the Nawab's favourite wife. It was stormed in 1857 by the British during the Indian Rebellion and witnessed within its walls the slaughter of all 2,200[3] sepoy mutineers who had made it a stronghold during their Siege of Lucknow. The site now houses the National Botanical Research Institute of India.

Origin

The garden was laid out in about 1800 as a royal garden by Nawab Saadat Ali Khan. It was later improved upon by Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the last native ruler of Oudh, during the first half of the 19th century, who used it as his summer villa. The garden has a small pavilion in the middle, which was likely the scene of innumerable performances of the Ras-lilas, and Kathak dances, music and poetic 'mehfils' and other cultural activities which the last Nawab had a great appreciation for, indeed possibly too great a one as history has judged him to have been over-fond of his leisure interests.

Stormed in Indian Rebellion

During the Indian Rebellion, the Sikander Bagh was used as one of many strongholds of sepoy mutineers during their siege of the British Residency in Lucknow. It stood in the way of the Commander-in-Chief Sir Colin Campbell's planned route to relieve the besieged Residency.

On the morning of 16 November 1857, whilst passing by its eastern side in a southerly direction, in a sunken lane, the British force was surprised and stopped in its tracks by overwhelmingly heavy fire coming from the Sikander Bagh. A staff officer remarked to a comrade "If these fellows allow one of us to get out of this cul-de-sac alive, they deserve every one of them to be hanged".[4] The cavalry were jammed together, unable to advance, and the high banks on either side seemed to offer an impassable barrier to artillery. However Blunt of the Bengal Horse Artillery led his troop and "conquering the impossible",[5] brought them with their guns into an open space to the east of the Sikandar Bagh, galloping through enemy fire. Here he unlimbered with remarkable coolness and self-possession. The six guns opened fire on the Sikandar Bagh. Sappers and miners demolished part of the earth banks which allowing two 18-pounder heavy guns of Travers's battery of the Artillery Brigade to be brought up out of the lane.[6] After half an hour of bombardment from a range of only 80 yd (73 m), an aperture was created in the south-east angle of the wall in a bricked-up doorway, "an ugly blind hole", about 3 ft (0.91 m) square and 3 ft (0.91 m) off the ground. Although only large enough to admit a single man with difficulty it was immediately rushed under heavy fire by some of the 93rd Highlanders and some men of the 4th Punjab Infantry (4th P.I.) under Lieutenant McQueen, 14 managing to enter the Sikaddar Bagh.

At the same time the rest of the 4th P.I. under Lieutenant Paul assaulted the gateway. The gate was in the process of being closed by the mutineers, when Subadar Mukarab Khan, 4th P.I., a Pathan of Bajaur, one of the leading men of the attack, thrust his left arm and shield between its folds, thus preventing it being shut and barred. Though his left arm was wounded, he still managed to keep his shield between the folds by holding it with his right hand until the door was forced. This took place whilst Lt. McQueen's party and some of the Highlanders, who had entered by the breach, came from the rear of the many defenders of the gateway. After a long hand-to-hand struggle the British forced their way in greater numbers into the Sikandar Bagh through the gate, and through the breach which had been enlarged by the sappers. Slowly forced back, the main body of about 2,000 mutineers took refuge in a large 2-storied building and the high-walled enclosure behind it. The 2 doors to the enclosure were assaulted by the 4th P.I. Lt. McQueen led the assault against the right gate, and Lt. Willoughby tackled the left. The defenders had expected an attack from the opposite quarter and had bricked up the door to their rear and in doing so blocked their retreat. After a long struggle they were all slain, no quarter being given.[7] With cries such as "Cawnpore! You bloody murderers",[8] it was clear that the British attackers blamed these mutineers for the slaughter of European civilians earlier in the Mutiny, including women and children, particularly during the Siege of Cawnpore, which caused outrage throughout British India and in Britain.[9] Lord Roberts who witnessed the assault later recalled: "'Inch by inch they were forced back to the pavilion, and into the space between it and the north wall, where they were all shot or bayoneted. There they lay in a heap as high as my head, a heaving, surging mass of dead and dying inextricably entangled. It was a sickening site, one of those which even in the excitement of battle and the flush of victory, make one feel strongly what a horrible side there is to war. The wounded men could not get clear of their dead comrades, however great their struggles, and those near the top of this ghastly pile vented their rage and determination on every British officer who approached, by showering upon him abuse of the foulest description".[10]

Those killed or wounded during the assault included 9 officers and 90 men of the 93rd Highlanders,[11] and 3 officers and 69 men from the 4th Punjabi Infantry.[12]

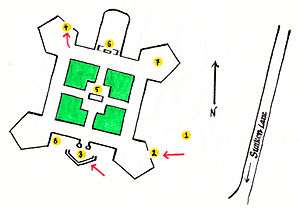

Diagram of assault

Key:[13] (1) Position of 18-pounder guns; (2) Breach made in wall; (3) Gateway; (4) Bastion stormed from inside by 4th. Punjab Infantry Regt., cutting off enemy's retreat; (5) Centre pavilion with verandah; (6) One-storied building overlooking whole garden with own courtyard behind; (7) East bastion, exploded, killing Lt. Paul, in command of 4th P.I.; (8) Spot occupied by Sir Colin Campbell, C-in-C, and Staff from 18 to 22 November.

Aftermath

After the fighting, the British and loyal native Punjab Infantry dead were buried in a deep trench. Later elephants were used to drag the corpses of the mutineers out of the Sikandar Bagh,[14][15] where they were slightly covered over in a ditch which they themselves had recently dug outside the north wall in order to strengthen the defences.[16]

The 4th Punjab Infantry remained quartered in the Sikandar Bagh until Lucknow was evacuated by the British 11 days later on 27 November, while the Commander-in-Chief and his staff occupied a site to the west of the gate, under the south wall, from 18 to 22 November.[17]

In early 1858 Felice Beato photographed the Sikandar Bagh, showing skeletal remains strewn across the grounds of the interior. These were apparently disinterred or rearranged to heighten the photograph's dramatic impact.[18]

Victoria Crosses awarded

It is said that more Victoria Crosses were awarded for that single day than ever, many for the assault on the Sikandar Bagh. The recipients were as follows:

- 53rd Regiment of Foot

- Private Charles Irwin - among the first to enter, elected by privates

- Private James Kenny - bravery and bringing up ammunition under fire, elected by privates

- Lieutenant Alfred Ffrench - one of the first to enter the building, elected by officers

- 90th Regiment of Foot

Sgt Samuel Hill and Major John Guise - for going to the aid of wounded, elected by the regiment

- 93rd Regiment of Foot (Sutherland Highlanders)

- Captain William Stewart - elected by the officers

- Colour Sergeant James Munro - for rescuing Captain Walsh

- Sergeant David Mackay - elected by the privates

- Sergeant John Paton - elected by the NCOs in the regiment

- Lance Corporal John Dunlay

- Private Peter Grant -

- 1st Madras (European) Fusiliers

- Private John Smith

- 1st Bengal (European) Fusiliers

- Lieutenant Francis Brown - for assisting a wounded soldier

- HMS Shannons Naval Brigade

- Lieutenant Nowell Salmon

- Lieutenant Lieut Thomas Young - for, with William Hall, keeping their battery of guns firing after the other gun crews were casualties

- Leading Seaman John Harrison

- Foretop Captain William Hall

- Able Seaman Edward Robinson

Memorials of the assault

Articles such as cannonball, swords and shields, parts of muskets and rifles, dug out of the garden over the years are now displayed in the NBRI Exhibition and scars from cannonball on the old walls of the garden still bear witness to the event.

Another visible reminder of the battle is the statue, erected some years ago in the old campus of the garden, of Uda Devi, a Pasi (a Dalit community) lady,[19] who fought side by side with the besieged mutineers. Attired in male battle dress, she had perched herself atop a tree in the garden, gun in hand, and kept the British attackers at bay until her ammunition was exhausted, upon which she dropped dead to the ground, her body riddled with bullets. As far as the legend goes Uda Devi was one of the female bodyguards of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. She was fiercely dedicated. Trained in martial Arts and espionage she also learned the art of guerrilla warfare and fought with her gun till the last bullet. The British were also surprised and stunned by her marksmanship until she was spotted by the soldiers, who fired relentlessly at her till she died from her wounds.

Image gallery

The Sikandar Bagh Gateway in ruins, date supposedly 1870, but likely to be post-1883, from missing minarets.

The Sikandar Bagh Gateway in ruins, date supposedly 1870, but likely to be post-1883, from missing minarets.

Notes

- See photograph of 1883 with minarets in place, though damaged, and later b&w photo without minarets, said to be 1870, but clearly post-1883

- Kaye's & Malleson's History of the Indian Mutiny, 6 vols., London, 1889, vol.4, chap. 9, pp.127-133

- Regimental History of the 4th Battalion, 13th Frontier Force Rifles (Wilde's), anonymous author, c.1930, p.21. Central Library of RMA, Sandhurst, reprinted 2005

- Remark quoted in Blackwood's Magazine, (quoted in Kaye & Malleson, vol.4, p.128/9)

- The narrative in this passage follows Kaye & Malleson, p128

- Kaye & Malleson, 1889, p.121

- 13th Frontier Force Regimental History, 2005, pp.20-21

- Hibbert, Christopher (1980). The Great Mutiny, India 1857. Penguin Books. p. 240.

- Trotter, Lionel James. The History of the British Empire in India, 1844-1862, chap. 7: "The rebels died hard by the hands of men still maddened with the fearful memories of Cawnpore"

- Field Marshal Lord Roberts, Forty-one Years in India 1897, page 182.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1980). The Great Mutiny, India 1857. Penguin Books. p. 242.

- Regimental History, 2005, p.21

- After diagram in Regimental History, 2005, p.22/23

- Lehmann, Joseph (1964). All Sir Garnet; a life of Field-Marshal Lord Wolseley. London, J. Cape. p. 61. ASIN B0014BQSRS.

- Trotter, Lionel James. The History of the British Empire in India, 1844-1862, chap. 7.

- Field Marshal Lord Roberts, Forty-one Years in India 1897, page 192.)

- Regimental History, 2005,pp.21,22/23

- Gartlan, Luke (2007). Felix Beato in Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 0415972353.

- Safvi, Rana (7 April 2016). "The Forgotten Women of 1857". The Wire. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

References

- NIC District Unit, Lucknow. Historical Places At Lucknow. Accessed 2 November 2006.

- Regimental History of the 4th Battalion, 13th Frontier Force Rifles (Wilde's), anonymous author, c.1930. Central Library of RMA, Sandhurst, reprinted 2005

- FIBIS (Families in British India Society) website wiki.fibis.org, "Battle of Secundra Bagh" (list of VC winners)

- Brown University Library; Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection: Photographic views of Lucknow taken after the Indian Mutiny. Accessed 2 November 2006.

- Christopher Hibbert The Great Mutiny, India 1857, Penguin Books, 1980, chap 18, pp. 339-344

- Kaye's & Malleson's History of the Indian Mutiny, 6 vols., London, 1889, vol.4, chap. 9, pp. 127–133

- Joseph Lehmann All Sir Garnet; a life of Field-Marshal Lord Wolseley J. Cape of London, 1964, pp. 56-68

- Field Marshal Lord Roberts, Forty-one Years in India 1897, chap. page 192

- Lionel James Trotter, The History of the British Empire in India, 1844-1862, London, 1866, page 247

Further reading

Indian Mutiny by Saul David 2002 ISBN 0-14-100554-8

My Indian Mutiny Diary by WH Russell 1967 ISBN 0-527-78120-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sikandar Bagh. |

- Indian Mutiny 1857-58 The British Empire website

- Action at Sikandar Bagh Google Books

- Shannon's Naval Brigade at Secundra Bagh Google Books