Subedar

Subedar (Urdu: صوبیدار) is a historical civil or military rank originally relating to a senior official of the Mughal Empire who governed an assigned "Subah" ("province"). Under the British rule in India, "subedar" was the designation accorded to an Indian military officer of a rank equivalent to that of captain.

| Subedhar | |

|---|---|

| Subah-Dar | |

| Country | Mughal Empire India Pakistan |

| Engagements | Mughal-Maratha Wars Battles involving the Mughal Empire |

Today the rank is maintained by the Indian Army and Pakistani Army.

History

Thomas Pitt, (1699)[2]

Origin

The rank of Subedar was derived from subahdar: the title denoting a governor of a province in the Mughal Empire.

The rank of "Subedar" was created when the Mughal administration divided their territories into separate Subahs ("provinces"). Each province was governed by a Subedar who had full martial authority. Not much is known about the role of the early Mughal Subedars but the rank was superseded in importance during the late 18th century by that of Nawab.

The Hindvi Swaraj may have also developed the rank of "Subedar", thus explaining how they quickly replaced the authority of the Great Moghul in India. However Shivaji separated Military from Civil Administration and hence Subahders were only Military Chieftains. Example: Subedar Tanaji Malusare.

Role in British India

Subedar or subadar was the second highest rank of Indian officer in the military forces of British India, ranking below "British commissioned officers" and above "Local non-commissioned officers". Indian officers were promoted to this rank on the basis of both length of service and individual merit.

A subedar was senior to a jemadar and junior to a subedar-major in the infantry regiments of the Indian Army under British rule. The cavalry equivalent was risaldar. Both jemadars and risaldars wore two stars as rank insignia.[3]

The rank was introduced in the East India Company's presidency armies (the Bengal Army, the Madras Army and the Bombay Army) to make it easier for British officers to communicate with Indian troops. It was thus important for subedars to have some competence in English. In an order dated November 1755 the structure of an infantry company in the HEIC's newly raised infantry regiments provided for one subedar, four jemadars, 16 NCOs and 90 sepoys (private soldiers). This was to remain the approximate proportion until the number of British junior officers in a regiment increased later in the 18th century.[4]

Until 1866, the rank was the highest an Indian soldier could achieve in the army of British India. A subedar's authority was confined to other Indian troops, and he could not command British troops. Promoted from the ranks and usually advanced through seniority based on long service; the typical subedar of this period was a relatively elderly veteran with limited English, whose extensive regimental experience and practical knowledge was not matched by formal education or training.[5]

Before the Partition of India, subedars were known as Viceroy's commissioned officers (VCOs). After 1947, this term was changed to junior commissioned officers. It was not until the 1930s that significant numbers of Indian cadets began to be appointed as King's Commissioned Officers (KCOs) from either Sandhurst or the Indian Military Academy at Dehra Dun.[6]

After independence

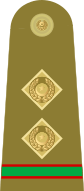

After independence, which came in 1947 with the Partition of India, the former Indian Army was divided between India and Pakistan. In the Pakistan Army, the rank has been retained, but the distinguishing ribbon band on the shoulder strap is now red-green-red. After Bangladesh separated from Pakistan, the Bangladesh Army also retained the rank, changing the ribbon colours to red-purple-red, but in Bangladesh the title of subedar was changed in 1999 to senior warrant officer.

Insignia and uniform

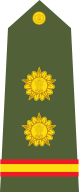

Until 1858, subedars wore two epaulettes with small bullion fringes on each shoulder. After 1858, they wore two crossed golden swords, or, in the Gurkha regiments, two crossed golden kukris, on each side of the collar of the tunic or on the right breast of the kurta. After 1900, subedars wore two pips on each shoulder. A red-yellow-red ribbon was introduced under each pip after World War I. After World War II, this ribbon was moved to lie between the shoulder title and the rank insignia (two brass stars on both shoulders).

During the period of British rule, subedars and other VCOs wore distinctive uniforms that combined features of both British and Indian military dress.[7]

Maratha Empire

In the Maratha Empire Brahmins from all three subcastes: Deshastha, Chitpavan and Karhade, were appointed as subedars and commanders of hill forts. The Deshastha Brahmins were the dominant faction during the time of Shivaji and his two sons.[8]

Under the Maratha Confederacy subedars were answerable to Peshwa commanders.

Hyderabad and Swat state

In the Princely State of Hyderabad under the Nizam, the top rank of administrators and tax collectors were called subedars. Although they were responsible directly to the Nizam they also held a degree of responsibility to the Great Moghul in Delhi.,

In Yousafzai state of Swat, subedar was both military and tax collector. Subedars were responsible directly to Wali of swat.

References

- Blackburn, Terence R. A Miscellany of Mutinies and Massacres in India p. 11

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-O5cqkphDI

- Creese, Michael. Swords Trembling in Their Scabbards. The Changing Status of Indian Officers in the Indian Army 1757-1947. p. xiii. ISBN 9-781909-982819.

- Creese, Michael. Swords Trembling in Their Scabbards. The Changing Status of Indian Officers in the Indian Army 1757-1947. p. 26. ISBN 9-781909-982819.

- Creese, Michael. Swords Trembling in Their Scabbards. The Changing Status of Indian Officers in the Indian Army 1757-1947. p. 28. ISBN 9-781909-982819.

- Mason, Philip. A Matter of Honour. An Account of the Indian Army, its Officers and Men. pp. 453–466. ISBN 0-333-41837-9.

- coloured illustrations by A.C. Lovett contained in "The Armies of India", Lt. Get Sir George MacMunn, ISBN 0 947554 02 5

- B. K. Ahluwalia; Shashi Ahluwalia (1984). Shivaji and Indian Nationalism. Cultural Publishing House. p. 47.

External links

- www.Bharat-Rakshak.com/Army/Ranks.html - Illustration of various military insignias including three subedar insignia designs.