Science-Fiction Plus

Science-Fiction Plus was an American science fiction magazine published by Hugo Gernsback for seven issues in 1953. In 1926, Gernsback had launched Amazing Stories, the first science fiction magazine, but he had not been involved in the genre since 1936, when he sold Wonder Stories. Science-Fiction Plus was initially in slick format, meaning that it was large-size and printed on glossy paper. Gernsback had always believed in the educational power of science fiction, and he continued to advocate his views in the new magazine's editorials. The managing editor, Sam Moskowitz, had been a reader of the early pulp magazines, and published many writers who had been popular before World War II, such as Raymond Z. Gallun, Eando Binder, and Harry Bates. Combined with Gernsback's earnest editorials, the use of these early writers gave the magazine an anachronistic feel.

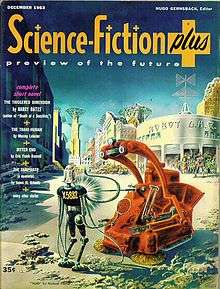

Sales were initially good, but soon fell. For the last two issues Gernsback switched the magazine to cheaper pulp paper, but the magazine remained unprofitable. The final issue was dated December 1953.

In addition to the older writers he published, Moskowitz was able to obtain fiction from some of the better-known writers of the day, including Clifford Simak, Murray Leinster, Robert Bloch, and Philip José Farmer, and some of their stories were well-received, including "Spacebred Generations", by Simak, "Strange Compulsion", by Farmer, and "Nightmare Planet", by Leinster. He also published several new writers, but only one, Anne McCaffrey, went on to a successful career in the field. Science fiction historians consider the magazine a failed attempt to reproduce the early days of the science fiction pulps.

Publication history

The first science fiction (sf) magazine, Amazing Stories, was launched in 1926 by Hugo Gernsback at the height of the pulp magazine era.[2][3] It helped to form science fiction as a separately marketed genre,[2] and although Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in a bankruptcy in 1929, he quickly started several more sf magazines, including Air Wonder Stories and Science Wonder Stories.[3] The two magazines were soon combined as Wonder Stories, which lasted until 1936, when Gernsback sold it to Ned Pines of Beacon Magazines.[4] Gernsback remained in the publishing business as proprietor of several profitable magazines, but he did not return to the sf field for nearly seventeen years, when Science-Fiction Plus appeared.[5]

Gernsback hired Sam Moskowitz to edit the new magazine, and produced a dummy issue in November 1952 that was never distributed or intended for sale; it was printed for trademark purposes, and contained only stories by Gernsback himself, under his own name and several pseudonyms. The first issue produced for sale was dated March 1953. It was a slick, meaning that it was in large format and was printed on high-quality paper; this was a step up from the cheap paper used in the leading science fiction magazines of the day, and sf historian Mike Ashley notes that in theory this should have given Gernsback a marketing edge. The price, 35 cents, was also competitive. Sales were initially good, and Science-Fiction Plus remained on a monthly schedule until June, but when the circulation began to slip, the magazine became bimonthly beginning with the August issue. Gernsback distributed Science-Fiction Plus along with his technical magazines, and if the circulation of the new magazine had been comparable to that of his other titles, it would have been profitable despite the more expensive slick paper, but sales were insufficient for it to continue. In October Gernsback cut costs by switching to cheaper pulp paper, but only one further issue, dated December 1953, appeared.[5][6]

Contents and reception

Gernsback believed from the beginning of his involvement with science fiction in the 1920s that the stories should be instructive,[8] although it was not long before he found it necessary to print fantastical and unscientific fiction in Amazing Stories to attract readers.[9] During Gernsback's long absence from sf publishing, from 1936 to 1953, the field evolved away from his focus on facts and education.[10][11] The Golden Age of Science Fiction is generally considered to have started in the late 1930s and lasted until the mid-1940s, bringing with it "a quantum jump in quality, perhaps the greatest in the history of the genre", according to science fiction historians Peter Nicholls and Mike Ashley.[12] However, Gernsback's views were unchanged. In his editorial in the first issue of Science-Fiction Plus, he gave his view of the modern sf story: "the fairy tale brand, the weird or fantastic type of what mistakenly masquerades under the name of Science-Fiction today!" and he stated his preference for "truly scientific, prophetic Science-Fiction with the full accent on SCIENCE".[11] In the same editorial, Gernsback called for patent reform to give science fiction authors the right to create patents for ideas without having patent models because many of their ideas predated the technical progress needed to develop specifications for their ideas. The introduction referenced the numerous prescient technologies described throughout Ralph 124C 41+.[13]

The managing editor, Sam Moskowitz, also had a long history in the field, having helped organize the First World Science Fiction Convention in 1939. He too had strong views about what constituted good science fiction, though his views did not always coincide with those of his publisher:[5][6] Gernsback's focus was on the educational potential of sf, while Moskowitz was a fan of the early writers in the field, from before the Golden Age.[11] Moskowitz was the one in charge of obtaining stories, and he succeeded in acquiring work by many of the best-known names in sf, including Clifford Simak, Murray Leinster, Robert Bloch, James H. Schmitz, and Philip José Farmer, but he also bought many stories by writers from the early years of the genre, such as Raymond Gallun, Eando Binder, and Harry Bates. The result was a magazine that both Ashley and fellow sf historian Donald Lawler describe as old-fashioned, despite its smart appearance: in Ashley's words, Science-Fiction Plus had "a feeling of archaism", and he adds "for a magazine to be 'slick', it didn't just have to look slick, it had to feel it, but in the case of Science-Fiction Plus all that glittered clearly was not gold".[5] Lawler agrees, describing the magazine as "an anachronism", and "dull from first to last".[11] As part of Gernsback's attempt to encourage stories that contained plausible scientific predictions, he created a symbol made up of a sphere labeled "SF", with a five-pointed star atop it. He placed the first of these awards on a story of his own, "Exploration of Mars", in the first issue, in what Lawler describes as "a characteristic self-tribute".[11]

Gernsback paid two to three cents per word for fiction, which was competitive with the leading magazines of the day,[14] and despite the magazine's anachronistic approach, Moskowitz was able to publish some well-received stories. Lawler describes Simak's story, "Spacebred Generations", as a "gem", and cites Farmer's "Strange Compulsion" as "the high point in story quality for the entire run".[11] Ashley praises the same two stories, and considers "Nightmare Planet", by Murray Leinster, from the June 1953 issue, as equal in quality. Moskowitz attempted to find and develop new writers, and published the first story by Anne McCaffrey, "Freedom of the Race", which appeared in the October 1953 issue. However, none of Moskowitz's other new writers lasted in the field, and he rejected McCaffrey's subsequent submissions.[5]

As well as fiction, Gernsback included departments such as "Science Questions and Answers", "Science News Shorts", and other science-related non-fiction; these, like the fiction, were reminiscent of the Gernsback magazines of two decades earlier. In Ashley's opinion, the artwork was of variable quality; Frank R. Paul, who had worked with Gernsback on his earlier magazines, appeared in every issue, but although this brought back the ambience of the early science fiction magazines, Paul's work had not improved over the years. Ashley notes that Alex Schomburg, who was also a frequent contributor, did provide some high-quality covers.[5]

Bibliographic details

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/6 | 1/7 | |||||

| Issues of Science-Fiction Plus, identifying volume and issue numbers. Sam Moskowitz was editor throughout.[11] | ||||||||||||

The magazine was subtitled Preview of the Future;[11] Sam Moskowitz was the managing editor of all seven issues of Science-Fiction Plus, and assembled the issues; Gernsback was listed as editor and wrote the editorials.[5] The magazine remained "large pulp" size throughout its run. The first five issues were printed on glossy paper; the final two were pulp. It was priced at 35 cents throughout, and all issues were 64 pages. There are no reprint anthologies from the magazine, nor any foreign editions. In the mid-1950s many stories from Science-Fiction Plus were used in early issues of the Australian magazine Science-Fiction Monthly,[11] with the first four issues almost entirely drawn from Science-Fiction Plus.[15] Several covers and much interior artwork from the magazine were reproduced in a Swedish sf magazine titled Häpna!, which began publication in 1954.[16]

References

- Ashley (2005), p. 385.

- Ashley, Mike; Nicholls, Peter; Stableford, Brian (July 14, 2014). "Amazing Stories". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- Ashley, Mike; Edwards, Malcolm; Nicholls, Peter (August 23, 2014). "SF Magazines". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- Ashley (2000), p. 91.

- Ashley (2005), pp. 58–59.

- Stableford, Brian; Nicholls, Peter; Langford, David; Ashley, Mike (May 24, 2015). "Science-Fiction Plus". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- Ashley (2005), p. 381.

- Ashley (2000), p. 50.

- Ashley (2000), p. 54.

- Ashley (2004), p. 252.

- Lawler (1985), pp. 541–545.

- Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike (April 9, 2015). "Golden Age of SF". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- "Science Fiction Plus v01n01".

- de Camp (1953), pp. 115–116.

- Stone (1985), pp. 537–539.

- Moskowitz (1983), p. 92.

Sources

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines:The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Ashley, Mike (2004). "The Gernsback Days". In Ashley, Mike; Lowndes, Robert A.W. (eds.). The Gernsback Days: A Study of the Evolution of Modern Science Fiction From 1911 to 1936. Holicong, Pennsylvania: Wildside. ISBN 0-8095-1055-3.

- Ashley, Mike (2005). Transformations:The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-779-4.

- de Camp, L. Sprague (1953). Science-Fiction Handbook: The Writing of Imaginative Fiction. New York: Hermitage House. OCLC 559803608.

- Lawler, Donald (1985). "Science-Fiction Plus". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 541–545. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Moskowitz, Sam (2013) [1983]. "Anatomy of a Collection: The Sam Moskowitz Collection". In Hall, Hal W. (ed.). Science/Fiction Collections: Fantasy, Supernatural and Weird Tales. New York: Routledge. pp. 79–110. ISBN 0-917724-49-6.

- Stone, Graham (1985). "Science-Fiction Monthly (1955–1957)". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 537–539. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

External links