Martin Schongauer

Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–53, Colmar – 2 February 1491, Breisach), also known as Martin Schön ("Martin beautiful") or Hübsch Martin ("pretty Martin") by his contemporaries,[2][3] was an Alsatian engraver and painter. He was the most important printmaker north of the Alps before Albrecht Dürer, a younger artist who collected his work. Schongauer is the first German painter to be a significant engraver, although he seems to have had the family background and training in goldsmithing which was usual for early engravers.[4]

.jpg)

The bulk of Schongauer's surviving production is 116 engravings,[5] all with his monogram but none dated,[6] which were well known not only in Germany, but also in Italy and even made their way to England and Spain.[7] Vasari says that Michelangelo copied one of his engravings, in the Trial of Saint Anthony. His style shows no trace of Italian influence, but a very clear and organised Gothic, which draws from both German and Early Netherlandish painting.

Recent scholarship, building on the work of Max Lehrs, attributes 116 engravings to him, with many also being copied by other artists (including his monogram), as was common in the period. His prolific contemporary Israhel van Meckenem did close copies of 58 engravings, exactly half of Schongauer's output, and took motifs or figures from more, as well as apparently engraving some drawings that are now lost.[8]

There are some fine drawings, including ones dated and signed with his monogram, and a surviving few paintings in oil and fresco.

Biography

Schongauer was born about 1450–53 in Colmar,[9] Alsace, the third of four or five sons of Caspar Schongauer,[10] a goldsmith and patrician from Augsburg who moved to Colmar about 1440; Caspar became a master of the goldsmith's guild in 1445, which probably required a residence of five years.[11] He presumably taught his son the art of engraving, which is a distinct and difficult skill that goldsmiths had long used on metal vessels.[12] Two of his brothers worked as goldsmiths in Colmar, while another also became a painter.[13] Colmar is now in France but was then part of the Holy Roman Empire and German-speaking.

Most unusually for a Gothic or Renaissance artist, he was sent to university, presumably with the intention of turning him into a priest or lawyer, and matriculated at the University of Leipzig in 1465,[14] but seems to have left after a year. At this time university students often began at the age of twelve or thirteen.[15] He was traditionally thought to have been trained as an engraver by Master E. S., but scholars now doubt this, partly because Schongauer's prints took some time to develop the technical advances that a pupil of Master E. S. would have been taught.[16]

He is thought to have trained as a painter with Colmar's main local master Caspar Isenmann (d. 1472), a neighbour of his parents, who was greatly influenced by the Early Netherlandish painting of Rogier van der Weyden and others, and had perhaps studied in the Netherlands, and Schongauer's few surviving pictures reflect this. This was probably around 1466 and 1469;[17] he was recorded as back in Colmar in 1469.[18] His older brother Ludwig Schongauer had probably preceded him in the workshop.

His earlier engravings also show clear influences from several Early Netherlandish painters, suggesting that he followed the traditional pattern of a wanderjahre travelling at the end of his training. One drawing, dated 1469, is a copy of the figure of Christ in Rogier van der Weyden's Beaune Altarpiece, presumably made in front of the painting.[19] Various details of costume, and the exotic plants in the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, have suggested to some scholars that he also visited Spain, and possibly Portugal.[20]

He returned to Colmar and had established a workshop by 1471, when payments were made for an altarpiece for the Dominican church there, which is now in the museum and regarded as a workshop production.[21] His Madonna in the Rose Garden, long displayed in the church in Colmar it was made for, but moved to the Dominican church nearby in 1973,[22] is dated 1473 (his only dated painting). Its style corresponds with the earliest of his engravings, which have been placed in a broadly agreed sequence based on their technique and style, both of which show considerable development.[23] In some cases a terminus ante quem is provided by copies in various media that can be dated.[24]

The economics of fifteenth-century printmaking are unclear, and though his prints spread his fame widely across Europe, he may have relied more on the income from his "major vocation" of painting.[25]

He died in Breisach in 1491, perhaps before reaching the age of forty. He had been engaged since 1488 in painting a large Last Judgment in the cathedral there,[26] and was recorded as a citizen there in June 1489.[27] This was the largest mural painting north of the Alps, and was incomplete at his death.[28]

The following year Dürer, on his wanderjahre, travelled to Colmar to meet him, only to find he had died. Dürer was an admirer who collected his drawings and no doubt prints. His own print of the Flight into Egypt, in his Life of the Virgin series, includes the same two exotic trees as Schongauer's, as a hommage.[29] In Germany Dürer, whose prints became known over the decade following, was seen as the next leader of the tradition Schongauer had dominated for twenty years.[30]

His pupils included Hans Burgkmair the Elder, the Augsburg-based painter and designer of woodcuts (but not engravings), who was with him from 1488 to 1490.[31] The painted portrait of Schongauer, with his coat of arms at top left, is unusual for a fifteenth-century artist, but the panel now in Munich appears to be made well after his death, and is perhaps a copy of a drawing or painting made at the date on the painting, 1483. It is attributed to Hans Burgkmair the Elder, and the lost original may have been by his father, Thoman Burgkmair, who very plausibly met Schongauer in Augsburg, where Schongauer is recorded as at least visiting.[32]

Another of Schongauer's pupils, the painter Urbain Huter, has long been considered as the main author of the Buhl Altarpiece, a work very close in design and execution both to Schongauer's own engravings and to the production of Schongauer's painting workshop. Some engravers whose prints are often copies of Schongauer's, and whose original compositions are close to his style, are assumed to have been pupils of his. These include Master i.e, attributed with 55 prints by Lehrs, 31 copies of his master, Master BM, and Master A G, attributed with 34 prints, 13 copies of his master.[33]

Paintings

Only a few of his paintings survive, the most notable being the Madonna in the Rose Garden painted for St Martin's Church, Colmar and today displayed in the Dominican church nearby.[34] This is a German subject, associated in particular with Cologne and Stephan Lochner, but Schongauer gives it a treatment very much in the Netherlandish style. It has been cut down at the top and sides to fit the elaborate later carved frame.[35]

The Musée d´Unterlinden in Colmar possesses the largest collection. Two double-sided shutters (probably made to surround a sculpted central section) from the "Orlier Altarpiece", dated c. 1470–75, show the Annunciation on the outer faces and a Nativity and Saint Anthony with donor portrait within. These are regarded as largely the work of the master,[36] while the twenty-four panels from the doors of an altarpiece for the Dominican church are regarded as mainly painted by the workshop, no doubt to his designs.[37] A Nativity in Berlin is attributed to him.

The small Holy Family in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna is close in style to his engravings, and not much larger than some. Many everyday details, such as the grapes in the basket, the wheat carried by Joseph, and the flask of water in the niche in the wall, can be treated as allusions to the theology of the subject, in the tradition of Netherlandish painting.[38]

A watercolour and gouache study of paeony leaves and flowers (now Getty Museum) surfaced in 1988; it relates to the flowers in the Madonna in the Rose Garden.[39]

The Breisach frescos remain on the west and south walls of the cathedral, though "in ruinous condition".[40]

- Paintings and drawings

.jpg) Madonna, Angel and Child, 17.5 x 11.5 cm, 1470–75

Madonna, Angel and Child, 17.5 x 11.5 cm, 1470–75 Adoration by the Shepherds, Berlin

Adoration by the Shepherds, Berlin Mary, detail, Orlier altarpiece

Mary, detail, Orlier altarpiece.jpg) Orlier altarpiece

Orlier altarpiece Portrait of a young woman, c. 1478

Portrait of a young woman, c. 1478 Drawing of a Bust of a Monk Assisting at Communion

Drawing of a Bust of a Monk Assisting at Communion Bust of a Man in a Hat Gazing Upward, drawing

Bust of a Man in a Hat Gazing Upward, drawing Drawing of an old man with fur collar and hat, 1475

Drawing of an old man with fur collar and hat, 1475

Engravings

One hundred and sixteen engravings are generally recognised as by his hand. Many of his pupils' plates as well as his own are signed, M†S, as are many copies probably by artists with no connection to him. He is thought to have begun signing engravings in the early 1470s.[41] The rarest survives in three impressions,[42] and unlike most other printmakers of the century, examples have probably survived of all the engravings he made.[43]

The great majority of his subjects are religious, but there are a handful of comic scenes of ordinary life such as the early Peasant Family Going to Market or the Two Apprentices Fighting, which may reflect his background in a goldsmith's house.[44] A print of an elephant is a unique venture into the popular "prodigy" genre; it turns out that an elephant was indeed being toured around Germany in 1483, before drowning in a canal near Muiden.[45]

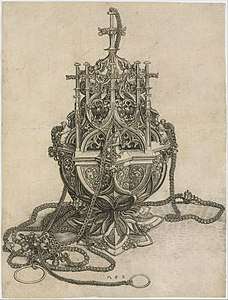

He also produced nine of the first ornament prints, initially intended to be used by craftsmen in various media, including woodcarvers and goldsmiths, as patterns for the elaborate and sophisticated designs.[46] There are also two prints of metalwork objects, a censer and crosier.[47]

From his family background and time at university he was no doubt familiar with the emerging bourgeoisie of trade and the professions who provided the core market for high quality engravings,[48] but the subjects from classical mythology so popular in German prints of the next century, and already present in Italian ones, do not appear at all in his work.

The generally agreed sequence of his engravings shows an increasing sophistication of technique, but the most crowded and detailed, but highly organized, compositions are placed rather early, with "late-Gothic complexity" giving way to simpler compositions with more empty space and "an almost classical orderliness and decorum".[49] But some of the busy early prints were his most popular and influential, as shown by the number of copies of them. These include The Temptation of St Anthony, the [Rest on] the Flight into Egypt, Death of the Virgin and Christ Carrying the Cross.[50]

There are a number of series of engravings which show this development, from the twelve "crowded and turbulent" scenes in the Passion series, perhaps of about 1480,[51] through the Twelve Apostles,[52] and the circular coats of arms with wild men,[53] to the late circular Evangelist's symbols and the Wise and Foolish Virgins, perhaps of around 1490.[54] By the time of his pair showing the Annuciation with each figure occupying its own sheet, often thought to be his last prints, the background is only represented by a simple groundline.[55]

He went beyond Master E. S. in the system of depicting volume by means of cross-hatching (lines in two directions) which was further developed by Dürer, and was the first engraver to curve parallel lines, probably by rotating the plate against a steady burin.[56] He also developed a burin technique producing deeper lines on the plate, which meant that more impressions could be taken before the plate became worn.[57]

According to Arthur Mayger Hind, Schongauer was one of the first German engravers to "rise above the Gothic limitations both of setting and type" and that he "actualises an idea of beauty which in its nearer approach to more absolute ideals appeals to a far more universal appreciation" than earlier engravers such as Master E. S.[58]

With Master E.S., he was the first northern printmaker not only to have his prints very widely copied by other printmakers, but to have his designs taken by painters, sculptors and artists in all media.[59] The demons in his The Temptation of St Anthony established the hybrids of fish, bird and insect types followed by Hieronymus Bosch and other artists throughout the next century.[60]

Major print rooms possess good collections of Schongauer's prints, most of which are relatively common for fifteenth-century prints,[61] although impressions vary in quality a good deal. The different watermarks found suggest that impressions were printed over considerable periods, with most made when the copper plates were showing signs of wear. The Rest on the Flight into Egypt survives in some sixty impressions, though only seven are "of the first quality".[62] For the large Christ Carrying the Cross, the largest engraving yet made, the equivalent figures are about seventy and fifteen.[63]

- Engravings

Peasant Family Going to Market

Peasant Family Going to Market

.jpg) [Rest on] the Flight into Egypt

[Rest on] the Flight into Egypt Death of the Virgin

Death of the Virgin Christ Carrying the Cross, 28.8 x 43.3 cm.

Christ Carrying the Cross, 28.8 x 43.3 cm. Saint John on Patmos

Saint John on Patmos St. Martin

St. Martin- Ecce Homo, engraving from the Passion series

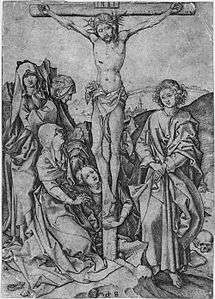

Crucifixion from the Passion series

Crucifixion from the Passion series St.Michael

St.Michael Madonna and Child in the Courtyard

Madonna and Child in the Courtyard Noli me Tangere

Noli me Tangere

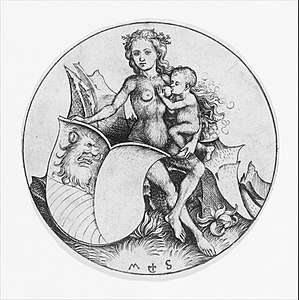

Wild Woman Holding a Shield with a Lion's Head

Wild Woman Holding a Shield with a Lion's Head The Ox of St. Luke

The Ox of St. Luke The Third Wise Virgin

The Third Wise Virgin The Second Wise Virgin

The Second Wise Virgin The First Foolish Virgin

The First Foolish Virgin The Fifth Foolish Virgin

The Fifth Foolish Virgin Archangel of the Annunciation

Archangel of the Annunciation The Censer

The Censer Ornament with Owl Mocked by Day Birds

Ornament with Owl Mocked by Day Birds

Notes

- This painting, in Munich, appears to be a 16th-century copy, possibly by Hans Burgkmair, of a lost original painting or drawing, presumably of 1483 (the date on the painting), perhaps by Thoman Burgkmair. See Hutchison, 6 note 2; Shestack, 87

- "Der hübsche Martin... Martin Schongauer". smb.museum. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Martin Schongauer German engraver". britannica.com. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Shestack, biography

- Max Lehrs' count, followed by Shestack and Hutchison, though there is now doubt over one – see Bartrum, 20

- Shestack, biography, #34

- Ducay for Spain

- Shestack, 119–205, 183–194

- Hutchison, 6; Shestack, biography. Once thought to be around 1440 or even earlier, his birthdate has been moved later in recent scholarship, based on working backwards from the few known dates. Bartrum, 20 has "c. 1450".

- Four per Hutchison, 6 – her note 3 explains that the 5th son, Caspar, is mentioned only by one source of the next century; five per Bartrum, 20

- Hutchison, 6

- Snyder, 280

- Snyder, 230

- Shestack, biography; Hutchison, 6

- Shestack, biography; Hutchison, 6

- Shestack, biography

- Shestack, biography

- Hutchison, 6

- Shestack, biography; Bartrum, 20. The date was actually added decades later by Albrecht Dürer when he owned the drawing; Snyder, 280–281

- Shestack, biography; Hutchison, 6 and note 6. The trees are a date palm and a dracaena draco or Canary Islands dragon tree, then very much a rare newcomer found in a few gardens in Iberia. One of the demons attacking Saint Anthony is said to based on an Iberian species of lizard.

- Bartrum, 20

- "Une chronologie mouvementée". Les Dominicains de Colmar. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Shestack, biography, #34, 35, 36, 37; Hutchison, 6

- For example, Shestack, #s 68–73, copied on the font of St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna, datable to 1481.

- Shestack, biography

- Shestack, biography

- Bartrum, 20

- Hutchison, 6

- Bartrum, 35; Snyder, 282

- Bartrum, 21; Hutchison, 6

- Bartrum, 130

- See Hutchison, 6 note 2; Shestack, 87

- Shestack, # 116-122

- Bartrum, 20

- Snyder, 231

- "Orlier Altarpiece" at the Musée d´Unterlinden.

- "Altarpiece of the Dominicans" at the Musée d´Unterlinden.

- Snyder, 231–232

- Bartrum, 20; image; Getty page

- Shestack, biography

- Shestack, biography

- Hyatt Major, 130

- Shestack, biography

- Shestack, #79; Snyder, 284

- Snyder, 285; Shestack, 87; Bartrum, 8 on prodigy prints

- Shestack, biography, # 106–109; Snyder, 285

- Shestack, # 110, 111

- Bartrum, 8

- Shestack, biography (quoted); Snyder, 285

- Hutchison, 6–7; Shestack, # 37, 40, 41; Bartrum, 21; Snyder, 282–284

- Shestack, #s 51–82

- Shestack, #s 68–73

- Shestack, #s 90–97

- respectively, Shestack, #s 98–100 and #101–104

- Snyder, 285–286

- Hyatt Major, 130

- Bartrum, 21

- Hind, Arthur M. A History of Engraving & Etching From the 15th Century to the Year 1914. Dover Publications. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9780486209548. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- Shestack, Introduction; Hutchinson, 6

- Hyatt Major, 133; Snyder, 282

- Shestack, biography; Bartrum, 20

- Hutchison, 6

- Hutchison, 7

References

- Bartrum, Giulia; German Renaissance Prints, 1490–1550; British Museum Press, 1995, ISBN 0-7141-2604-7

- A. Hyatt Mayor, Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, ISBN 0-691-00326-2, fully available online

- Hutchison, Jane Campbell, in KL Spangeberg (ed), Six Centuries of Master Prints, Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993, nos 6–8, ISBN 0931537150

- Alan Shestack, Fifteenth Century Engravings of Northern Europe, 1967, National Gallery of Art (Catalogue), LOC 67-29080 (no page numbers; a biography is followed by numbered entries, 34–115)

- Snyder, James. Northern Renaissance Art, 1985, Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0136235964

- Maria del Carmen Lacarra Ducay. 'Influencia de Martin Schongauer en los primitivos aragoneses', Boletin del Museo e Instituto 'Camon Aznar'’, vol. xvii (1984), pp. 15–39.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Martin Schongauer. |

- www.kulturpool.at, complete(?) set of images of the engravings in Austrian collections, mostly the Albertina in Vienna.

- Martin Schongauer exhibition catalogs