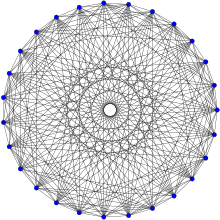

Schläfli graph

In the mathematical field of graph theory, the Schläfli graph, named after Ludwig Schläfli, is a 16-regular undirected graph with 27 vertices and 216 edges. It is a strongly regular graph with parameters srg(27, 16, 10, 8).

| Schläfli graph | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vertices | 27 |

| Edges | 216 |

| Radius | 2 |

| Diameter | 2 |

| Girth | 3 |

| Automorphisms | 51840 |

| Chromatic number | 9 |

| Properties | Strongly regular Claw-free Hamiltonian |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

Construction

The intersection graph of the 27 lines on a cubic surface is a locally linear graph that is the complement of the Schläfli graph. That is, two vertices are adjacent in the Schläfli graph if and only if the corresponding pair of lines are skew.[1]

The Schläfli graph may also be constructed from the system of eight-dimensional vectors

- (1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0),

- (1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1), and

- (−1/2, −1/2, 1/2, 1/2, 1/2, 1/2, 1/2, 1/2),

and the 24 other vectors obtained by permuting the first six coordinates of these three vectors. These 27 vectors correspond to the vertices of the Schläfli graph; two vertices are adjacent if and only if the corresponding two vectors have 1 as their inner product.[2]

Alternately, this graph can be seen as the complement of the collinearity graph of the generalized quadrangle GQ(2,4).

Subgraphs and neighborhoods

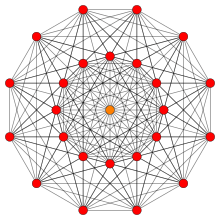

The neighborhood of any vertex in the Schläfli graph forms a 16-vertex subgraph in which each vertex has 10 neighbors (the numbers 16 and 10 coming from the parameters of the Schläfli graph as a strongly regular graph). These subgraphs are all isomorphic to the complement graph of the Clebsch graph.[1][3] Since the Clebsch graph is triangle-free, the Schläfli graph is claw-free. It plays an important role in the structure theory for claw-free graphs by Chudnovsky & Seymour (2005).

Any two skew lines of these 27 belong to a unique Schläfli double six configuration, a set of 12 lines whose intersection graph is a crown graph in which the two lines have disjoint neighborhoods. Correspondingly, in the Schläfli graph, each edge uv belongs uniquely to a subgraph in the form of a Cartesian product of complete graphs K6 K2 in such a way that u and v belong to different K6 subgraphs of the product. The Schläfli graph has a total of 36 subgraphs of this form, one of which consists of the zero-one vectors in the eight-dimensional representation described above.[2]

Ultrahomogeneity

A graph is defined to be k-ultrahomogeneous if every isomorphism between two of its induced subgraphs of at most k vertices can be extended to an automorphism of the whole graph. If a graph is 5-ultrahomogeneous, it is ultrahomogeneous for every k; the only finite connected graphs of this type are complete graphs, Turán graphs, 3 × 3 rook's graphs, and the 5-cycle. The infinite Rado graph is countably ultrahomogeneous. There are only two connected graphs that are 4-ultrahomogeneous but not 5-ultrahomogeneous: the Schläfli graph and its complement. The proof relies on the classification of finite simple groups.[4]

See also

- Gosset graph - contains the Schläfli graph as an induced subgraph of the neighborhood of any vertex.

Notes

- Holton & Sheehan (1993).

- Bussemaker & Neumaier (1992).

- Cameron & van Lint (1991). Note that Cameron and van Lint use an alternative definition of these graphs in which both the Schläfli graph and the Clebsch graph are complemented from their definitions here.

- Buczak (1980); Cameron (1980); Devillers (2002).

References

- Buczak, J. M. J. (1980), Finite Group Theory, Ph.D. thesis, Oxford University. As cited by Devillers (2002).

- Bussemaker, F. C.; Neumaier, A. (1992), "Exceptional graphs with smallest eigenvalue-2 and related problems", Mathematics of Computation, 59 (200): 583–608, doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1992-1134718-6.

- Cameron, Peter Jephson (1980), "6-transitive graphs", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 28 (2): 168–179, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(80)90063-5. As cited by Devillers (2002).

- Cameron, Peter Jephson; van Lint, Jacobus Hendricus (1991), Designs, graphs, codes and their links, London Mathematical Society student texts, 22, Cambridge University Press, p. 35, ISBN 978-0-521-41325-1.

- Chudnovsky, Maria; Seymour, Paul (2005), "The structure of claw-free graphs", Surveys in combinatorics 2005 (PDF), London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., 327, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 153–171, MR 2187738.

- Devillers, Alice (2002), Classification of some homogeneous and ultrahomogeneous structures, Ph.D. thesis, Université Libre de Bruxelles.

- Holton, D. A.; Sheehan, J. (1993), The Petersen Graph, Cambridge University Press, pp. 270–271.