Schilling telegraph

The Schilling telegraph is a needle telegraph invented by Pavel Schilling in the nineteenth century. It consists of a bank of needle instruments (six as developed for use in Russia) which between them display a binary code representing a letter or numeral. Signals were sent from a piano-like keyboard, and an additional circuit was provided for calling attention at the receiving end by setting off an alarm.

The code was read from the position of paper discs suspended on threads. These had different colours on the two sides. Each disc was turned by electromagnetic action on a magnetised needle.

Overview

Schilling's telegraph is one of a type called needle telegraphs. These are telegraphs that use a coil of wire as an electromagnet to deflect a small magnet shaped like a compass needle. The position of the needle imparts the telegraphed information to the person receiving the message. Schilling's 1832 demonstration telegraph in St. Petersburg used six wires for signalling, one wire for calling, and a common return, making eight wires in all. Each signal wire was connected to one of six needle instruments which together displayed a binary code. The calling wire had the same function as the ringing signal on a telephone, but in this case was connected to a seventh needle.[1]

Schilling's telegraph was developed to the stage where a project was initiated by the government to install it in Russia, but the idea was abandoned after Schilling died. See the Pavel Schilling article for more historical details. Telegraphy in Russia subsequently used more advanced designs.[2]

Signal needles

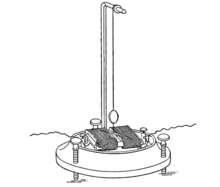

Each needle was hung above its coil horizontally by a silk thread. A paper disc was attached to the thread coloured white on one side and black on the other. When the coil was energised, either the black side or the white side would turn towards the observer, depending on the polarity of the applied current.[3] In some models, Schilling attached a platinum-plated wire to the thread which descended into a container of mercury. The end of the wire in the mercury was paddle shaped so that the motion of the needle was damped and oscillation suppressed.[4] Two permanently magnetised steel pins were screwed into the wooden base to hold the needle in the neutral position, that is, so that the paper disc was edge on, not displaying a colour. A second needle underneath the coil was used for better linking with these permanent magnets.[5]

Sending equipment

For the sending equipment, the earliest demonstrations of the Schilling telegraph crudely touched the ends of the wires to the poles of the battery manually. These were connected to six separate needle instruments, rather than a bank of them in one assembly. Later, a more sophisticated arrangement was devised – messages were sent from a piano-like keyboard with alternating white and black keys.[6] There were sixteen keys altogether, each white and black pair of keys operating one of the wires. Positive or negative voltage was applied to the wire depending on whether the white or black key was pressed. Changing the colour of key used resulted in the needle swinging in the opposite direction, thus showing the opposite side of the dual-coloured disc. The polarities were arranged such that the colour of the keys corresponded to the colour of the disc displayed on the needle.[7] See Artemenko for a photograph of this equipment.

The switches underneath the keys operated in the following manner. Metal bridges fixed underneath the keys dipped into two reservoirs of mercury. One of these reservoirs was permanently connected to one or other of the battery poles depending on the colour of the key, and the other was permanently connected to one of the signal wires.[8] The keys for the common wire connect to the opposite polarity of the battery to that of the same colour of the signal wire keys. A limitation of this system is that only the set of black keys, or the set of white keys, can be used at any one time.[9][note 1]

Calling needle

The calling needle was similar to the signal needles with some additional mechanical apparatus. The needle was suspended by metal wire, rather than a silk thread, and had attached to it a horizontal arm. When a call was made the arm turned and pushed over a lever with a lead weight attached which fell under gravity and released the detent of a clockwork alarm. In specifying a separate calling line and mechanism, Schilling was following the arrangements on the electrochemical telegraph of Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring.[10] Schilling had become familiar with Sömmerring's work while a diplomat in Munich and frequently visited Sömmerring to see and assist with his telegraph.[11]

Coding

The Schilling telegraph used binary coding. Each needle either displayed a disc or remained in the neutral position, corresponding to binary "1" or "0" respectively in modern notation. Six needles were needed to generate sufficient codepoints for the Russian alphabet – the modern alphabet has 33 letters, and there were even more in the nineteenth century.[12] The ability to choose between displaying the white discs or the black discs doubled the codespace, but not all codepoints were used. Codepoints that spanned the fewest keys were preferentially used. For the Latin alphabet, used in Western European countries, five needles were sufficient.[13]

| Six-needle code table[14] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Fahie suggests that Schilling must have used two batteries so that the polarity of signal wires could be freely set. He clearly was not aware that the code table was limited to one colour or the other for each codepoint, so this was not necessary. His source was a Russian description of the instrument from the Paris Electrical Exhibition of 1881 which he describes as "very obscurely written" (Fahie, p. 315).

References

- Artemenko

- Yarotsky, p. 713

- Fahie, pp. 309–310

- Fahie, pp. 310–311

- Yarotsky, p. 711

- Fahie, pp. 313–314

- Artemenko

- Fahie, p. 313

- Artemenko

- Fahie, p. 312

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Bermel, p. 20

-

Yarotsky, p. 712

- Garratt, pp. 273–274

- Dawson, pp. 133–138

- Yarotsky, p. 712

Bibliography

- Artemenko, Roman, "Pavel Schilling - inventor of the electromagnetic telegraph", PC Week, vol. 3, iss. 321, 29 January 2002 (in Russian).

- Dawson, Keith, "Electromagnetic telegraphy: early ideas, proposals and apparatus", pp. 113–142 in, Hall, A. Rupert; Smith, Norman (eds), History of Technology, vol. 1, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016 ISBN 1350017345.

- Fahie, John Joseph, A History of Electric Telegraphy, to the Year 1837, London: E. & F.N. Spon, 1884 OCLC 559318239.

- Garratt, G.R.M., "The early history of telegraphy", Philips Technical Review, vol. 26, no. 8/9, pp. 268–284, 21 April 1966.

- Huurdeman, A.A., The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, Wiley, 2003 ISBN 0471205052.

- Yarotsky, A.V., "150th anniversary of the electromagnetic telegraph", Telecommunication Journal, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 709–715, October 1982.