Needle telegraph

A needle telegraph is an electrical telegraph that uses indicating needles moved electromagnetically as its means of displaying messages. It is one of the two main types of electromagnetic telegraph, the other being the armature system as exemplified by the telegraph of Samuel Morse in the United States. Needle telegraphs were widely used in Europe and the British Empire during the nineteenth century.

.jpg)

Needle telegraphs were suggested shortly after Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that electric currents could deflect compass needles in 1820. Pavel Schilling developed a telegraph using needles suspended by threads. This was intended for installation in Russia for government use, but Schilling died in 1837 before it could be implemented. Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Eduard Weber built a telegraph that was used for scientific study and communication between university sites. Carl August von Steinheil adapted Gauss and Weber's rather cumbersome apparatus for use on various German railways.

In England, William Fothergill Cooke started building telegraphs, initially based on Schilling's design. With Charles Wheatstone, Cooke produced a much improved design. This was taken up by several railway companies. Cooke's Electric Telegraph Company, formed in 1846, provided the first public telegraph service. The needle telegraphs of the Electric Telegraph Company and their rivals were the standard form of telegraphy for the better part of the nineteenth century in the United Kingdom. They continued in use even after the Morse telegraph became the official standard in the UK in 1870. Some were still in use well in to the twentieth century.

Early ideas

The history of the needle telegraph began with the landmark discovery, published by Hans Christian Ørsted on 21 April 1820, that an electric current deflected the needle of a nearby compass.[1] Almost immediately, other scholars realised the potential this phenomenon had for building an electric telegraph. The first to suggest this was French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace. On 2 October, André-Marie Ampère, acting on Laplace's suggestion, sent a paper on this idea to the Paris Academy of Sciences. Ampère's (theoretical) telegraph had a pair of wires for each letter of the alphabet with a keyboard to control which pair was connected to a battery. At the receiving end, Ampère placed small magnets (needles) under the wires. The effect on the magnet in Ampère's scheme would have been very weak because he did not form the wire into a coil around the needle to multiply the magnetic effect of the current.[2] Johann Schweigger had already invented the galvanometer (in September) using such a multiplier, but Ampère either had not yet got the news, or failed to realise its significance for a telegraph.[3]

Peter Barlow investigated Ampère's idea, but thought it would not work. In 1824 he published his results, saying that the effect on the compass was seriously diminished "with only 200 feet of wire". Barlow, and other eminent academics of the time who agreed with him, were criticised by some writers for retarding the development of the telegraph. A decade passed between Ampère's paper being read and the first electromagnetic telegraphs being built.[4]

Development

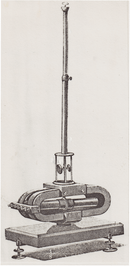

Schilling telegraph

It was not until 1829 that the idea of applying Schweigger style multipliers to telegraph needles was mooted by Gustav Theodor Fechner in Leipzig. Fechner, in other respects following the scheme of Ampère, also suggested a pair of wires for each letter (twenty-four in the German alphabet) laid underground to connect Leipzig with Dresden. Fechner's idea was taken up by William Ritchie of the Royal Institution of Great Britain in 1830. Ritchie used twenty-six pairs of wires run across a lecture room as a demonstration of principle.[5] Meanwhile, Pavel Schilling in Russia constructed a series of telegraphs also using Schweigger multipliers. The exact date that Schilling switched from developing electrochemical telegraphs to needle telegraphs is not known, but Hamel says he showed one in early development to Tsar Alexander I who died in 1825.[6] In 1832, Schilling developed the first needle telegraph (and the first electromagnetic telegraph of any kind) intended for practical use.[7] Tsar Nicholas I initiated a project to connect St. Petersburg with Kronstadt using Schilling's telegraph, but it was cancelled on Schilling's death in 1837.[8]

Schilling's scheme had some drawbacks. Although it used far fewer wires than proposed by Ampère or used by Ritchie, his 1832 demonstration still used eight wires, which made the system expensive to install over very long distances. Schilling's scheme used a bank of six needle instruments which between them displayed a binary code representing a letter of the alphabet. Schilling did devise a code that allowed the letter code to be sent serially to a single needle instrument, but he found that the dignitaries he demonstrated the telegraph to could understand the six-needle version more readily.[9] Transmission speed was very slow on the multi-needle telegraph, perhaps as low as four characters per minute, and even slower on the single-needle version. The reason for this was principally that Schilling had severely overdamped the movement of the needles by slowing them with a platinum paddle in a cup of mercury.[10] Schilling's method of mounting the needle by suspending it by a silk thread over the multiplier also had practical difficulties. The instrument had to be carefully levelled before use and could not be moved or disturbed while in use.[11]

Gauss and Weber telegraph

In 1833 Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Eduard Weber set up an experimental needle telegraph between their laboratory in the University of Göttingen and the university astronomical observatory about a mile and a half away where they were studying the Earth's magnetic field. The line consisted of a pair of copper wires on posts above rooftop height.[12] The receiving instrument they used was a converted laboratory instrument, of which the so called needle was a large bar magnet weighing a pound. In 1834, they replaced the magnet with an even heavier one, variously reported as 25,[13] 30,[14] and 100 pounds.[15] The magnet moved so minutely a telescope was required to observe a scale reflected from it by a mirror.[16] The initial purpose of this line was not telegraphic at all. It was used to confirm the correctness or otherwise of the then recent work of Georg Ohm, that is, they were verifying Ohm's law. They quickly found other uses, the first of which was the synchronisation of clocks in the two buildings. Within a few months, they developed a telegraph code that allowed them to send arbitrary messages. Signalling speeds were around seven characters per minute.[17] In 1835, they replaced the batteries of their telegraph with a large magneto-electric apparatus which generated telegraph pulses as the operator moved a coil relative to a bar magnet. This machine was made by Carl August von Steinheil.[18] The Gauss and Weber telegraph remained in daily service until 1838.[19]

In 1836, the Leipzig–Dresden railway inquired whether the Gauss and Weber telegraph could be installed on their line. The laboratory instrument was much too cumbersome, and much too slow to be used in this way. Gauss asked Steinheil to develop something more practical for railway use. This he did, producing a compact needle instrument which also emitted sounds while it was receiving messages. The needle struck one of two bells, on the right and left respectively, when it was deflected. The two bells had different tones so that the operator could tell which way the needle had been deflected without constantly watching it.[20]

Steinheil first installed his telegraph along five miles of track covering four stations around Munich.[21] In 1838, he was installing another system on the Nuremberg–Fürth railway line. Gauss suggested that he should use the rails as conductors and entirely avoid installing wires. This failed when Steinheil tried it because the rails were not well insulated from the ground, but in the process of this failure, he realised that he could use the ground as one of the conductors. This was the first earth-return telegraph put into service anywhere.[22]

Commercial use

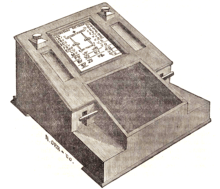

Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph

The most widely used needle system, and the first telegraph of any kind used commercially, was the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, employed in Britain and the British Empire in the 19th and early-20th centuries, due to Charles Wheatstone and William Fothergill Cooke. The inspiration to build a telegraph came in March 1836 when Cooke saw one of Schilling's needle instruments demonstrated by Georg Wilhelm Muncke in a lecture in Heidelberg (although he did not realise that the instrument was due to Schilling).[23] Cooke was supposed to be studying anatomy, but immediately abandoned this and returned to England to develop telegraphy. He initially built a three-needle telegraph, but believing that needle telegraphs would always require multiple wires,[24] he moved to mechanical designs.[25] His first effort was a clockwork telegraph alarm, which later went into service with telegraph companies.[26] He then invented a mechanical telegraph based on a musical snuff box. In this device the detent of the clockwork mechanism was released by the armature of an electromagnet.[27] Cooke carried out this work extremely quickly. The needle telegraph was completed within three weeks, and the mechanical telegraph within six weeks of seeing Muncke's demonstration.[28] Cooke attempted to interest the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in his mechanical telegraph for use as railway signalling, but it was rejected in favour of a system using steam whistles.[29] Unsure of how far his telegraph could be made to work, Cooke consulted Michael Faraday and Peter Mark Roget. They put him in touch with eminent scientist Charles Wheatstone and the two then worked in partnership.[30] Wheatstone suggested using a much improved needle instrument and they then developed a five-needle telegraph.[31]

The Cooke and Wheatstone five-needle telegraph was a substantial improvement on the Schilling telegraph. The needles instruments were based on the galvanometer of Macedonio Melloni.[32] They were mounted on a vertical board with the needles centrally pivoted. The needles could be directly observed and Schilling's delicate silk threads were entirely done away with. The system required five wires, a slight reduction on that used by Schilling, partly because the Cooke and Wheatstone system did not require a common wire. Instead of Schilling's binary code, current was sent through one wire to one needle's coil and returned via the coil and wire of another.[33] This scheme was similar to that employed by Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring on his chemical telegraph, but with a much more efficient coding scheme. Sömmerring's code required one wire per character.[34] Even better, the two needles energised were made to point to a letter of the alphabet. This allowed the apparatus to be used by unskilled operators without the need to learn a code – a key selling point to the railway companies the system was aimed at.[35] Another advantage was that it was much faster at 30 characters per minute.[36] It did not use heavy mercury as the damping fluid, but instead used a vane in air, a much better match for ideal damping.[37]

The five-needle telegraph was first put into service with the Great Western Railway in 1838.[38] However, it was soon dropped in favour of two-needle and single-needle systems.[39] The cost of multiple wires proved to be a more important factor than the cost of training operators.[40] In 1846, Cooke formed the Electric Telegraph Company with John Lewis Ricardo, the first company to offer a telegraph service to the public.[41] They continued to sell needle telegraph systems to railway companies for signalling, but they also slowly built a national network for general use by businesses, the press, and the public.[42] Needle telegraphs were officially superseded by the Morse telegraph when the UK telegraph industry was nationalised in 1870,[43] but some continued in use well in to the twentieth century.[44]

Other systems

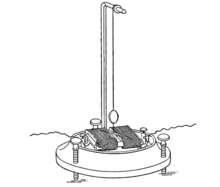

The Henley-Foster telegraph was a needle telegraph used by the British and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company, the main rival to the Electric Telegraph Company. It was invented in 1848 by William Thomas Henley and George Foster. It was made in both single-needle and two-needle forms which in operation were similar to the corresponding Cooke and Wheatstone instruments. The unique feature of this telegraph was that it did not require batteries. The telegraph pulses were generated by coils moving through a magnetic field as the operator worked the handles of the machine to send messages.[45] The Henley-Foster instrument was the most sensitive instrument available in the 1850s. It could consequently be operated over a greater distance and worse quality lines than other systems.[46]

The Foy-Breguet telegraph was invented by Alphonse Foy and Louis-François-Clement Breguet in 1842, and used in France. The instrument display was arranged to mimic the French optical telegraph system, with the two needles taking on the same positions as the arms of the Chappe semaphore (the optical system widely used in France). This arrangement meant that operators did not need to be retrained when their telegraph lines were upgraded to the electrical telegraph.[47] The Foy-Breguet telegraph is usually described as a needle telegraph, but electrically it is actually a type of armature telegraph. The needles are not moved by a galvanometer arrangement. They are instead moved by a clockwork mechanism that the operator must keep wound up. The detent of the clockwork is released by an electromagnetic armature which operates on the edges of a received telegraph pulse.[48]

According to Stuart M. Hallas, needle telegraphs were in use on the Great Northern Line as late as the 1970s. The telegraph code used on these instruments was the Morse code. Instead of the usual dots and dashes of different durations, but the same polarity, needle instruments used pulses of the same duration, but opposite polarities to represent the two code elements.[49] This arrangement was commonly used on needle telegraphs and submarine telegraph cables in the 19th century after Morse code became the international standard.[50]

Pseudoscience

Sympathetic needles were a supposed 17th century means of instantaneous communication at a distance using magnetised needles. Pointing one needle to a letter of the alphabet was supposed to cause its partner needle to point to the same letter at another location.[51]

References

- Fahie, p. 274

- Fahie, pp. 302–303

- Fahie, pp. 302–303

- Fahie, pp. 302–307

- Fahie, pp. 303–305

- Fahie, p. 309

- Yarotsky, p. 709

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Yarotsky, p. 712

- Dawson, p. 133

- Dawson, p. 129

- Fahie, p. 320

- Garratt, p. 275

- Shaffner, p. 137

- Fahie, p. 321

- Fahie, p. 322

- Garratt, p. 275

- Fahie, pp. 320–321

- Fahie, p. 325

- Garratt, p. 275

- Garratt, p. 275

- Garratt, pp. 275–276

- Kieve, pp. 17-18

- Shaffner, p. 187

- Shaffner, pp. 178–184

- Shaffner, p. 185

- Shaffner, pp. 185–190

- Shaffner, p. 185

-

Shaffner, p. 190

- Burns, p. 72

- Shaffner, pp. 190–191

- Kieve, pp. 17-18

- Hubbard, p. 39

- Shaffner, pp. 199–206

- Fahie, pp. 230–233

- Kieve, p. 49

- Shaffner, p. 207

- Dawson, pp. 133–134

- Bowers, p. 129

-

Mercer, p. 7

- Huurdeman, page 69

- Garratt, p. 277

- Kieve, p. 31

- Kieve, pp. 44–45, 49

- Kieve, p. 176

- Huurdeman, pp. 67–69

- Nature, pp. 111-112

- Schaffner, p. 288

- Shaffner, pp. 331-332

- Shaffner, pp. 325–328

- Hallas

- Bright, pp. 604–606

- Phillips, p. 271

Bibliography

- Bowers, Brian, Sir Charles Wheatstone: 1802–1875, IEE, 2001 ISBN 9780852961032.

- Bright, Charles, Submarine Telegraphs, London: Crosby Lockwood, 1898 OCLC 776529627.

- Dawson, Keith, "Electromagnetic telegraphy: early ideas, proposals and apparatus", pp. 113–142 in, Hall, A. Rupert; Smith, Norman (eds), History of Technology, vol. 1, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016 ISBN 1350017345.

- Fahie, John Joseph, A History of Electric Telegraphy, to the Year 1837, London: E. & F.N. Spon, 1884 OCLC 559318239.

- Garratt, G.R.M., "The early history of telegraphy", Philips Technical Review, vol. 26, no. 8/9, pp. 268–284, 21 April 1966.

- Hallas, Stuart M., "The single needle telegraph", www.samhallas.co.uk, retrieved and archived 29 September 2019.

- Hubbard, Geoffrey, Cooke and Wheatstone: And the Invention of the Electric Telegraph, Routledge, 2013 ISBN 1135028508.

- Huurdeman, Anton A., The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, Wiley, 2003 ISBN 0471205052

- Kieve, Jeffrey L., The Electric Telegraph: A Social and Economic History, David and Charles, 1973 OCLC 655205099.

- Mercer, David, The Telephone: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006 ISBN 9780313332074.

- Phillips, Ronnie J., "Digital technology and institutional change from the gilded age to modern times: The impact of the telegraph and the internet", Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 34, iss. 2, pp. 267-289, June 2000.

- Shaffner, Taliaferro Preston, The Telegraph Manual, Pudney & Russell, 1859 OCLC 258508686.

- Yarotsky, A.V., "150th anniversary of the electromagnetic telegraph", Telecommunication Journal, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 709–715, October 1982.

- "The progress of the telegraph: part VII", Nature, vol. 12, pp. 110–113, 10 June 1875.

External links