Schema (genetic algorithms)

A schema is a template in computer science used in the field of genetic algorithms that identifies a subset of strings with similarities at certain string positions. Schemata are a special case of cylinder sets; and so form a topological space.[1]

Description

For example, consider binary strings of length 6. The schema 1**0*1 describes the set of all words of length 6 with 1's at the first and sixth positions and a 0 at the fourth position. The * is a wildcard symbol, which means that positions 2, 3 and 5 can have a value of either 1 or 0. The order of a schema is defined as the number of fixed positions in the template, while the defining length is the distance between the first and last specific positions. The order of 1**0*1 is 3 and its defining length is 5. The fitness of a schema is the average fitness of all strings matching the schema. The fitness of a string is a measure of the value of the encoded problem solution, as computed by a problem-specific evaluation function.

Length

The length of a schema , called , is defined as the total number of nodes in the schema. is also equal to the number of nodes in the programs matching .[2]

Disruption

If the child of an individual that matches schema H does not itself match H, the schema is said to have been disrupted.[2]

Propagation of schema

In evolutionary computing such as genetic algorithms and genetic programming, propagation refers to the inheritance of characteristics of one generation by the next. For example, a schema is propagated if individuals in the current generation match it and so do those in the next generation. Those in the next generation may be (but don't have to be) children of parents who matched it.

The Expansion and Compression Operators

Recently schema have been studied using order theory.[3]

Two basic operators are defined for schema: expansion and compression. The expansion maps a schema onto a set of words which it represents, while the compression maps a set of words on to a schema.

In the following definitions denotes an alphabet, denotes all words of length over the alphabet , denotes the alphabet with the extra symbol . denotes all schema of length over the alphabet as well as the empty schema .

For any schema the following operator , called the of , which maps to a subset of words in :

Where subscript denotes the character at position in a word or schema. When then . More simply put, is the set of all words in that can be made by exchanging the symbols in with symbols from . For example, if , and then .

Conversely, for any we define , called the of , which maps on to a schema :

where is a schema of length such that the symbol at position in is determined in the following way: if for all then otherwise . If then . One can think of this operator as stacking up all the items in and if all elements in a column are equivalent, the symbol at that position in takes this value, otherwise there is a wild card symbol. For example, let then .

Schemata can be partially ordered. For any we say if and only if . It follows that is a partial ordering on a set of schemata from the reflexivity, antisymmetry and transitivity of the subset relation. For example, . This is because .

The compression and expansion operators form a Galois connection, where is the lower adjoint and the upper adjoint.[3]

The Schematic Completion and The Schematic Lattice

For a set , we call the process of calculating the compression on each subset of A, that is , the schematic completion of , denoted .[3]

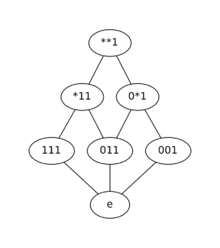

For example, let . The schematic completion of , results in the following set:

The poset always forms a complete lattice called the schematic lattice.

The schematic lattice is similar to the concept lattice found in Formal concept analysis.

References

- Holland, John Henry (1992). Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems (reprint ed.). The MIT Press. ISBN 9780472084609. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- "Foundations of Genetic Programming". UCL UK. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- Jack McKay Fletcher and Thomas Wennkers (2017). "A natural approach to studying schema processing". arXiv:1705.04536 [cs.NE].