Sceptre

A sceptre (British English) or scepter (American English) is a staff or wand held in the hand by a ruling monarch as an item of royal or imperial insignia. Figuratively, it means royal or imperial authority or sovereignty.

Antiquity

The Was and other types of staves were signs of authority in Ancient Egypt. For this reason they are often described as "sceptres", even if they are full-length staffs. One of the earliest royal sceptres was discovered in the 2nd Dynasty tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos. Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Pharaoh Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff. The staff with the longest history seems to be the heqa-sceptre (the "shepherd's crook").

The sceptre also assumed a central role in the Mesopotamian world, and was in most cases part of the royal insignia of sovereigns and gods. This is valid throughout the whole Mesopotamian history, as illustrated by both literary and administrative texts and iconography. The Mesopotamian sceptre was mostly called ĝidru in Sumerian and ḫaṭṭum in Akkadian.[1]

The ancient Tamil work of Tirukkural dedicates one chapter each to the ethics of the sceptre. According to Valluvar, "it was not his spear but the sceptre which bound a king to his people."[2] Sceptre in known as Sengol in Tamil language.

When India got independence, Lord Mountbatten has presented Jawaharlal Nehru with a Sceptre symbolising the transfer of power from colonial rule to independent India. It was said that, when Lord Mountbatten asked Jawaharlal Nehru about how to symbolise transfer of power, Nehru in turn asked his good counsel C. Rajagopalachari (fondly known as Rajaji). Rajaji was an ardent follower of Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam. He asked the 'head seer' in adheenam to help him to guide, how to symbolise the change of power. He recommended an ago old tradition in Tamil Nadu, which was to pass on 'Sengol' as an expression of transfer of power. He even recommended to a jeweller in Chennai (then known as 'Madras') who has the knowledge to craft an authentic sceptre.

Among the early Greeks, the sceptre (Ancient Greek: σκῆπτρον, skeptron, "staff, stick, baton") was a long staff, such as Agamemnon wielded (Iliad, i) or was used by respected elders (Iliad, xviii. 46; Herodotus 1. 196), and came to be used by judges, military leaders, priests, and others in authority. It is represented on painted vases as a long staff tipped with a metal ornament. When the sceptre is borne by Zeus or Hades, it is headed by a bird. It was this symbol of Zeus, the king of the gods and ruler of Olympus, that gave their inviolable status to the kerykes, the heralds, who were thus protected by the precursor of modern diplomatic immunity. When, in the Iliad, Agamemnon sends Odysseus to the leaders of the Achaeans, he lends him his sceptre.

Among the Etruscans, sceptres of great magnificence were used by kings and upper orders of the priesthood. Many representations of such sceptres occur on the walls of the painted tombs of Etruria. The British Museum, the Vatican, and the Louvre possess Etruscan sceptres of gold, most elaborately and minutely ornamented.

The Roman sceptre probably derived from the Etruscan. Under the Republic, an ivory sceptre (sceptrum eburneum) was a mark of consular rank. It was also used by victorious generals who received the title of imperator, and its use as a symbol of delegated authority to legates apparently was revived in the marshal’s baton.

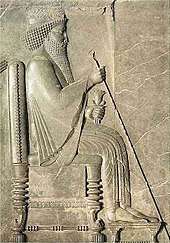

In the First Persian Empire, the Biblical Book of Esther mentions the sceptre of the King of Persia. Esther 5:2 "When the king saw Esther the queen standing in the court, she obtained favor in his sight; and the king held out to Esther the golden scepter that was in his hand. So Esther came near, and touched the top of the scepter."

Under the Roman Empire, the sceptrum Augusti was specially used by the emperors, and was often of ivory tipped with a golden eagle. It is frequently shown on medallions of the later empire, which have on the obverse a half-length figure of the emperor, holding in one hand the sceptrum Augusti, and in the other the orb surmounted by a small figure of Victory.

In literature

The codes of the right and the cruel sceptre are found in the ancient Tamil work of Tirukkural, dating back to the first century BCE. In Chapters 55 and 56, the text deals with the right and the cruel sceptre, respectively, furthering the thought on the ethical behaviour of the ruler discussed in many of the preceding and the following chapters.[3][4] The ancient treatise says it was not the king's spear but the sceptre that bound him to his people—and to the extent that he guarded them, his own good rule would guard him.[2]

Christian era

With the advent of Christianity, the sceptre was often tipped with a cross instead of with an eagle. However, during the Middle Ages, the finials on the top of the sceptre varied considerably.

In England, from a very early period, two sceptres have been concurrently used, and from the time of Richard I, they have been distinguished as being tipped with a cross and a dove respectively. In France, the royal sceptre was tipped with a fleur de lys, and the other, known as the main de justice, had an open hand of benediction on the top.

Sceptres with small shrines on the top are sometimes represented on royal seals, as on the great seal of Edward III, where the king, enthroned, bears such a sceptre, but it was an unusual form; and it is of interest to note that one of the sceptres of Scotland, preserved at Edinburgh, has such a shrine at the top, with little images of the Virgin Mary, Saint Andrew, and Saint James the Great in it. This sceptre was, it is believed, made in France around 1536 for James V. Great seals usually represent the sovereign enthroned, holding a sceptre (often the second in dignity) in the right hand, and the orb and cross in the left. Harold Godwinson appears thus in the Bayeux tapestry.

The earliest English coronation form of the 9th century mentions a sceptre (sceptrum), and a staff (baculum). In the so-called coronation form of Ethelred II a sceptre (sceptrum), and a rod (virga) appear, as they do also in the case of a coronation order of the 12th century. In a contemporary account of Richard I’s coronation, the royal sceptre of gold with a gold cross (sceptrum), and the gold rod with a gold dove on the top (virga), enter the historical record for the first time. About 1450, Sporley, a monk of Westminster, compiled a list of the relics there. These included the articles used at the coronation of Saint Edward the Confessor, and left by him for the coronations of his successors. A golden sceptre, a wooden rod gilt, and an iron rod are named. These survived until the Commonwealth, and are minutely described in an inventory of the regalia drawn up in 1649, when everything was destroyed.

For the coronation of Charles II of England, new sceptres with the Cross and the Dove were made, and though slightly altered, they are still in use today. Two sceptres for the queen consort, one with a cross, and the other with a dove, have been subsequently added.

The flags of Moldova, and Montenegro have sceptres on them.

See also

- Axis Mundi

- Baton

- Black Rod

- Ceremonial weapon

- Crown jewels

- Fool's sceptre

- Rood

- Staff of office

- Wand

References

- Bramanti, Armando (2017). "The Scepter (ĝidru) in Early Mesopotamian Written Sources". KASKAL. Rivista di storia, ambienti e culture del Vicino Oriente Antico. 2017 (14). ISBN 978-88-94926-03-3.

- Sundaram, P. S. (1990). Tiruvalluvar: The Kural (First ed.). Gurgaon: Penguin Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-01-44000-09-8.

- Tirukkuṛaḷ verses 541–560

- Pope, George Uglow (1886). The Sacred Kurral of Tiruvalluva Nayanar (PDF) (First ed.). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8120600223.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sceptres. |

| Look up sceptre in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |