Scanners Live in Vain

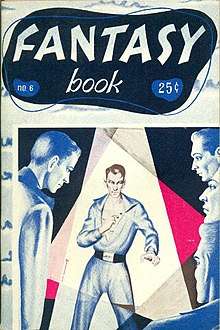

"Scanners Live in Vain" is a science fiction short story by American writer Cordwainer Smith (pen name of American writer Paul Linebarger). It was the first story in Smith's Instrumentality of Mankind future history to be published and the first story to appear under the Smith pseudonym. It first appeared in the semi-professional magazine Fantasy Book.

| "Scanners Live in Vain" | |

|---|---|

cover illustration by Jack Gaughan | |

| Author | Cordwainer Smith |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Science fiction |

| Published in | Fantasy Book volume 1 number 6 |

| Publication type | Periodical |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | January 1950 |

Significance

"Scanners Live in Vain" was judged by the Science Fiction Writers of America as one of the finest science fiction short stories prior to 1965 and, as such, was included in the anthology The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, 1929–1964. The story was nominated for a Retro-Hugo award in 2001. It has been published in Hebrew, Italian, French, German and Dutch translations.[1]

Plot summary

Cyborgs called scanners transformed by the Haberman Process, can, unlike humans stay alive (and not in cryogenic suspension) while traversing space but at a cost. The Haberman Process renders the scanners mute and able only to see and hear, not feel or smell or experience emotion. Unable to speak, they communicate by writing on tablets.

Martel is set apart by his marriage to an unaltered woman. He has just "cranched", a process which has temporarily restored him to a state of normalcy. The scanners' leader, Vomact (a member of the vom Acht or Vomact family that plays a prominent role in many of the Instrumentality stories), reveals that a man named Adam Stone will soon make public a method to circumvent the "Great Pain of Space" and allow space travel for humans not altered by the Haberman Process. This will make the scanners redundant. They decide to murder Stone.

Only Martel and Martel's friend, Chang, think this a bad plan. Martel warns Stone, who reveals that he has also developed a new technique that can undo the Haberman Process. A haberman assassin appears. Martel kills him. Stone restores Martel to his previous unmodified state. The Instrumentality of Mankind, which governs Earth and its colonies, decides to make the scanners into spaceship pilots, allowing them to still maintain their guild. The Instrumentality also covers up the failed murder plot and explains away the killing of the assassin in a particularly ironic way.

Background and reception

"Scanners Live in Vain" was Linebarger's first published science-fiction story other than "War No. 81-Q", which had been published in his high school magazine. (Linebarger had written the latter story at the age of 15.) "Scanners Live in Vain" was written in 1945. It had been rejected a number of times until its acceptance and publication in Fantasy Book in 1950. Fantasy Book was a low circulation obscure semi-professional magazine, but it was noticed by science fiction writer and editor Frederik Pohl. Pohl, who had himself, under a pseudonym, co-authored (with Isaac Asimov) a story which appeared in that issue, was impressed with the story's powerful style and imagery. Pohol republished it in 1952 in the more widely-read anthology Beyond the End of Time. Even then, the true identity of "Cordwainer Smith" remained a mystery and a topic of speculation for science fiction writers and fans.

Pohl has said that "Scanners Live in Vain" "is perhaps the chief reason why Fantasy Book is remembered". [2] Robert Silverberg called it "one of the classic stories of science fiction" and noted its "sheer originality of concept" and its "deceptive and eerie simplicity of narrative".[3] John J. Pierce, in his introduction to the anthology The Best of Cordwainer Smith, commented on the strong sense of religion it shares with Smith's other works, likening the Code of the Scanners to the Saying of the Law in H. G. Wells' The Island of Doctor Moreau.[4]

Graham Sleight lauded Smith's depiction of Martel's cranched perspective, calling it "a story about absence", but faulted his portrayal of Martel's wife Luci, whom he describes as "just a plot device".[5]

Science fiction scholar Alan C. Elms has suggested that the story reflects Smith's own deep psychological pain, symbolized by the "Great Pain of Space" (which is described in terms reminiscent of depression) and the isolation of the Scanners. The outcome of the story can by this interpretation be seen as indicative of his acceptance of help.[6]

A revised text, based on Linebarger's original manuscript, appears in the 1993 NESFA Press collection The Rediscovery of Man (where it is accompanied by a facsimile of his original cover letter) and the 2007 collection When the People Fell.

Notes

- ISFDB bibliography

- Pohl, Frederik (December 1966). "Cordwainer Smith". Editorial. Galaxy Science Fiction. p. 6.

- Silverberg, Robert. Science Fiction 101: Robert Silverberg's Worlds of Wonder. ibooks, New York, 2001.

- The Best of Cordwainer Smith, ed. John J. Pierce, Ballantine Books, New York, 1975.

- Yesterday's Tomorrows: Cordwainer Smith, reviewed by Graham Sleight, in Locus, April 2007; archived online October 18 2007; retrieved December 19, 2017

- Alan C. Elms, "The Creation of Cordwainer Smith", Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Nov., 1984), pp. 264-283.