Satgram Area

Satgram Area is one of the 14 operational areas of Eastern Coalfields Limited located mainly in Asansol subdivision of Paschim Bardhaman district and partly in Bankura Sadar subdivision in Bankura district, both in the state of West Bengal, India.

Satgram Area Location in West Bengal  Satgram Area Satgram Area (India) | |

| Coordinates | 23°40′30″N 87°04′58″E |

|---|---|

| Owner | |

| Company | Eastern Coalfields Limited |

| Website | http://www.easterncoal.gov.in/ |

History

The earliest attempts at coal mining in India by Suetonius Grant Heatly and John Sumner were at places such as Ethora, Chinakuri, Damulia (Damalia?) and others further west and not identified with modern-day places. The earliest attempts did mark the historic beginning of coal mining in India but did not produce much coal. When people such as William Jones, Jeremiah Homfrey and the Erskine brothers and companies such as Alexander & Co. again made attempts at mining coal they did so at places such as Narainkuri and Mangalpore, in and around what is now the Satgram Area of ECL. It was here that Dwarkanath Tagore and his Carr, Tagore and Company entered the fledgling world of coal mining.[1][2][3] In 1855, the East Indian Railway Company linked Raniganj with Kolkata, and ensured growth of the coal industry in the Raniganj Coalfield.[4]

Geography

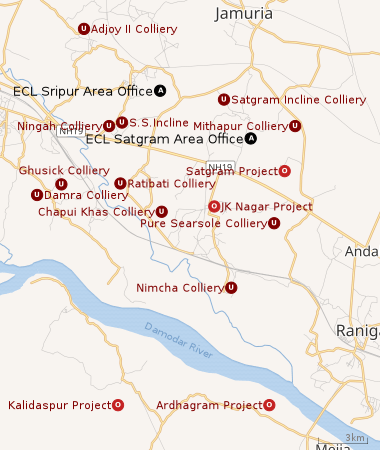

|

| Collieries in the Sripur and Satgram Areas of Eastern Coalfields U: Undergroud Colliery, O: Open Cast Colliery, S: Mining support, A: Administrative headquarters Owing to space constraints in the small map, the actual locations in a larger map may vary slightly |

Location

The Satgram Area is located around 23.674889°N 87.082754°E

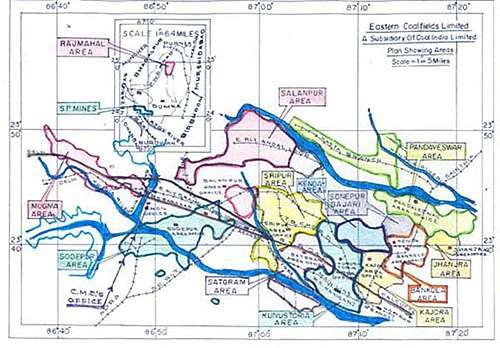

Located primarily in Paschim Bardhaman district, the Satgram extends into the coal mining areas in Bankura district, across the Damodar. It is bounded by the Sripur Area and Kunustoria Area on the north, Kajora Area/ Andal CD Block on the east, rural areas of Bankura district on the south and neighbourhoods of Asansol on the west.[5][6]

The map alongside shows some of the collieries in the Areas. However, as the collieries do not have individual pages, there are no links in the full screen map.

Coal mining

As per Shodhganga website, collieries in the Satgram Area are: Kalidaspur, J.K.Nagar, Satgram, Ratibati, Chapui Khas, Mithapur, Nimcha, Jemehari, Pure Searsole, Tirath, Kuardih, Ardhagram OCP and Seetaldasji OCP.[7]

As per ECL website telephone numbers, operational collieries in the Satgram Area in 2018 are: Chapui Khas Colliery, JK Nagar Project, Jemehari Colliery, Kalidaspur Project, Kuardi Colliery, Nimcha Colliery, Pure Searsole Colliery, Ratibati Colliery, Satgram Project and Satgram Incline.[8]

Mining plan

An overview of the proposed mining activity plan in Cluster 9, a group of 15 mines in the south-central part of Raniganj Coalfield and administratively under Satgram, Sripur and Kunustoria Areas of Eastern Coalfield, as of 2015–16, is as follows:[9]

1. Ratibati underground mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.09 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.12 mt, had an expected life of more than 40 years. Bogra (R-VI) seam was being worked with manual bord and pillar development in one panel and mechanized development in another panel. The coal mined was dispatched to M.S. Railway Siding in J. K. Nagar 14–15 km away.

2. Chapuikhas UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.05 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.06 mt, had an expected life of more than 50 years. Chapuikhas OC patch had an expected life of 1 year. Bogra (R-VI) seam is being developed by manual bord and pillar method of mining. An opencast patch measuring 7 ha was proposed to be worked within the mine leasehold to prevent illegal mining.

3. Amritnagar UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 1.14 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 1.14 mt, had an expected life of more than 30 years. Bogra (R-VI) seam was being worked in the mine. The mine was being developed using bord and pillar method of mining.

4. Tirat UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.06 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.08 mt, had an expected life of more than 10 years.

5. Kuardih UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.05 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.07 mt, had an expected life of more than 10 years. Kuardih OC patch had an expected life of 2 years. Ghusick – A R-IXA) seam was being depillared by manual bord and pillar method of mining with stowing. The coal mined was dispatched to M.S. Railway Siding in J. K. Nagar 14–15 km away.

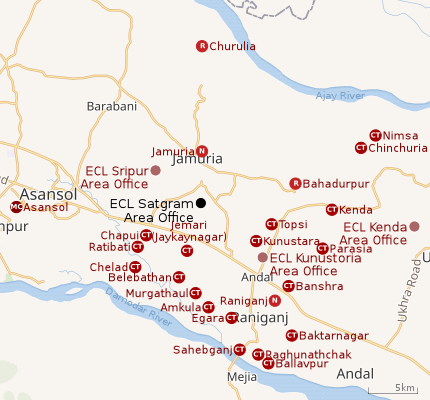

|

| Cities and towns in the eastern portion of Asansol Sadar subdivision in Paschim Bardhaman district MC: Municipal Corporation, CT: census town, N: neighbourhood, R: rural centre Owing to space constraints in the small map, the actual locations in a larger map may vary slightly |

6. Nimcha UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.31 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.40 mt, had an expected life of more than 50 years. Damalia OC patch had an expected life of 1 year. Nimcha Colliery consists of two units- (i) Nimcha 3 & 4 pit, (ii) Amkola 7 & 8 pit. The fairly steep gradient of the seams are around 1 in 25, and are of degree-II gassiness. In the Nimcha unit, R-IX seam is split into R-IX top and R-IX bottom seams. R-IX top seam is burnt. R-IX bottom seam is virgin. The R-VIII seam was being worked in the Nimcha unit. The Bogra (R-VI) and Satgram (R-V) seams are virgin in this unit. At the Amkola unit, R-IX combined is virgin. R-VIII and R-VII seams were being worked in Amkola unit. The coal mined was dispatched to Murgathole Railway Siding in J. K. Nagar 3–4 km away.

7. Ghusick UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.05 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.10 mt, had an expected life of more than 50 years. Nega top seam, with a gradient of 1 in 18, and degree-II gassiness, was being worked. The coal mined was dispatched to M.S. Railway Siding in J. K. Nagar 14–15 km away.

8. Kalipahari UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.05 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.10 mt, had an expected life of more than 50 years. Both Kalipahari OC patches A & B had an expected life of 2 years each and both OC patches C & D had an expected life of 1 year each. Kushadanga and Nega (top) seams were being depillared in the mine in conjunction with hydraulic sand stowing.

9. Muslia UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.04 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.05 mt, had an expected life of more than 50 years. Muslia OC had an expected life of 5 years. Ghusick seam was being developed in the mine.

10. New Ghusick UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.04 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.05 mt, had an expected life of more than 40 years. Nega (top) (R-VIIIT) seam was being worked with manual development by bord and pillar method of mining. Depillaring in some limited sectors were done with hydraulic sandstowing in the past.

11. Jemehari UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.03 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.04 mt, had an expected life of more than 10 years. Bogra (R-VI) seam was being developed by manual bord and pillar method of mining. However, production was affected because of some problems.

12. JK Nagar UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.35 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.87 mt, had an expected life of more than 30 years. In the proposed OC patches, while JK Nagar OC patch had an expected life of 3 years, both Pure Searsole and Mallick Basti OC patches had life of 1 year each. R-VI and R-V seams were being developed by the bord and pillar method with SDL and LHD. R-VII seam was being worked at Pure Searsole by the manual bord and pillar method.

13. Damra UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.04 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.06 mt, had an expected life of more than 10 years. Production was affected.

14. Mahabir UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.02 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.03 mt, had an expected life of more than 25 years. While both Mahabir OC patch and Narainkuri OC patch had an expected life of 4 years each, Egara OC patch had an expected life of 5 years. Plans were there to completely backfill these OC patches and reclaim them with plantation at the end of mining with no voids remaining.

15. Narainkuri UG mine, with normative annual production capacity of 0.54 million tonnes and peak annual production capacity of 0.54 mt, had an expected life of more than 25 years. There was a proposal to develop the mine by the bord and pillar method using Continuous Miner followed by depillaring in conjunction with sand stowing using SDL machines.

See also – Sripur Area#Mining plan for Satgram and Mithapur collieries

Illegal mining

Mines abandoned, after economic extraction is over, are the main sources of illegal mining. Illegal mining is generally done in small patches in a haphazard manner and mining sites keep on changing. Illegal mining leads to roof falling, water flooding, poisonous gas leaking, leading to the death of many labourers. As per the Ministry of Coal, Government of India, there are 203 illegal mining sites in ECL spread over Satgram, Sripur, Salanpur, Sodepur, Kunstoria, Pandveshwar, Mugma, Santhal Parganas Mines and Rajmahal.[10]

Subsidence

Traditionally many underground collieries have left a void after taking out the coal. As a result, almost all areas are facing subsidence. As per CMPDIL, there were 14 points of subsidence in the Satgram Area involving 1,336.52 hectares of land.[11] The rail tracks passing through the Satgram Area are at a constant risk of subsidence as there are seven abandoned galleries below the rail tracks.[12]

Migrants

Prior to the advent of coal mining, the entire region was a low-productive rice crop area in what was once a part of the Jungle Mahals. The ownership of land had passed on from local adivasis to agricultural castes before mining started. However, the Santhals and the Bauris, referred to by the colonial administrators as "traditional coal cutters of Raniganj" remained attached to their lost land and left the mines for agricultural related work, which also was more remunerative. It forced the mine-owners to bring in outside labour, mostly from Bihar, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh. In time the migrants dominated the mining and industrial scenario. The pauperization and alienation of the adivasis have been major points of social concern.[13][14]

Transport

Bardhaman–Asansol section | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Bardhaman-Asansol section, which is a part of Howrah-Gaya-Delhi line, Howrah-Allahabad-Mumbai line and Howrah-Delhi main line, passes through the Satgram Area.[20]

NH 19 (old number NH 2) and NH 14 (old number NH 60) cross at Raniganj.[21]

Healthcare

The Satgram Hospital of ECL in Jamuria has 50 beds. The Searsole TB Hospital of ECL in Raniganj has 50 beds.[22]

References

- Heatly, S. G. Tollemache (1842). "Contributions towards a History of the development of the Mineral Resources of India". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Asiatic Society of Bengal. 11, Part 2. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- Akkori Chattopadhyay, Bardhaman Jelar Itihas O Lok Sanskriti, Vol I, pp. 46-51, Radical, 2001, ISBN 81-85459-36-3

- Vikram Doctor, Editor, Special Features (20 September 2012). "Coal Dust in the Tagore Album". The Economic Times. Blogs. Retrieved 2 August 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- R. P. Saxena. "Indian Railway History timeline". IRFCA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Google maps

- "ECL Area Map". ENVIS Centre on Environmental Problems of Mining. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Coalmining impact on the Environment" (PDF). Chapter V: Table 5.2. shodganga.infibnet. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Area wise Closed User Group (CUG) Telephone Numbers" (PDF). Sripur Area. Eastern Coalfields Limited. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Environmental statement for Cluster 9 Group of Mines" (PDF). 2015–16. Central Mine Planning & Design Institute Limited. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- "Part I" (PDF). Chapter II: Problem of Illegal Mining and Theft of Coal. Indian Environmental Portal. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Coal mining impact on the environment" (PDF). Pages 78-81. Shodhganga. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Railways face cave in threat". The Times of India, 24 July 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Lahiri-Dutt, Kuntala (2003). "Unintended Collieries: People and Resources in Eastern India". Resource Management in Asia-Pacific, Working Paper No. 44. RMAP Working Papers. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Basu, Nirban (2012–13). "Industrialisation and Emergence of Labour Force in Bengal during The Colonial Period: Its Socio-Economic Impact" (PDF). Vidyasagar University Journal of History. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Bardhaman-Asansol MEMU 63505". India Rail Info.

- "Asansol Division System Map". Eastern Railway. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016.

- "South Eastern Railway Pink Book 2017-18" (PDF). Indian Railways Pink Book.

- "Asansol Division Railway Map". Eastern Railway.

- "Adra Division Railway Map". South Eastern Railway.

- "63509 Bardhaman-Asansol MEMU". Time Table. indiarailinfo. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- "Rationalisation of Numbering Systems of National Highways" (PDF). New Delhi: Department of Road Transport and Highways. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- "Detail list of Burdwan District Government Hospitals in West Bengal". acceptlive. Retrieved 11 August 2018.