Sarah Chapone

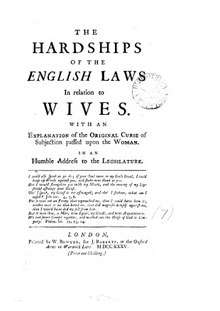

Sarah Chapone (11 December 1699 – 24 February 1764), born Sarah Kirkham and often referred to as Mrs Chapone,[lower-alpha 1] was an English legal theorist, pamphleteer, and prolific letter writer. She is best known for the treatise The Hardships of the English Laws in Relation to Wives, published anonymously in 1735.

Sarah Chapone | |

|---|---|

| Born | Sarah Kirkham 11 December 1699 Stanton, Gloucestershire, England |

| Died | 24 February 1764 (aged 64) Stanton, Gloucestershire, Great Britain |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | 18th century |

| Notable works | The Hardships of the English Laws in Relation to Wives |

| Children | 5 |

| Relatives | Hester Chapone (daughter-in-law) |

Background

Chapone lived and wrote in mid-18th-century England. At home, the period, known as the Georgian era, was marked by the dominance of Robert Walpole in Parliament. Abroad, military conflict between France and England was constant, until the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763—one year before Chapone's death.[1]

Feminism

Describing Chapone's theory as 'feminist' is an anachronism: the use of 'feminist' and 'feminism' to designate views favouring women's rights is attested only from the late 19th century.[2] However, scholars have identified aspects of Chapone's work that correspond to present-day feminist theory. For instance, philosopher Jacqueline Broad argues that 'Chapone deserves a prominent place in the history of feminist philosophy as one of the first writers consistently to apply what is now known as the republican concept of liberty to the situation of married women in early modern society'.[3]

Bluestocking circle

Scholars dispute whether Chapone was a bluestocking—an 18th-century term for an educated woman who belonged to tight-knit intellectual circles.[4][5][6][7] One difference between Chapone and most bluestockings was her social status: unlike Elizabeth Montagu and Mary Delany, she did not come from wealth or nobility.[8][9] Orr points out that Chapone, unlike most bluestockings, was particularly focussed on the law—bluestockings, while they were advocates for education and literary work by women, did not generally critique coverture.[10]

Personal life

Chapone was born in 1699 to Damaris and the Reverend Lionel Kirkham,[11] to a family largely of Anglican clergy.[10] She was raised in her father's rectory in Stanton, Gloucestershire, then quite a remote area.[12] She married Reverend John Chapone in 1725.[13] John Wesley, the Anglican theologian, had courted her; they later became friends and correspondents.[14] For nine years after her marriage, she operated a boarding school while raising five children.[13] Money was short, and the family moved frequently, until John became vicar of Badgeworth in 1745.[15][16]

Chapone was close with Mary Delany from 1715 (when Chapone was 16 and Delany 15) onwards.[13][17][18] In her autobiography, Delany describes Chapone, whom she nicknamed Sappho[lower-alpha 2]:

She had an uncommon genius and intrepid spirit, which though really innocent, alarmed my father, and made him uneasy at my great attachment to her. … She entertained me with her wit, and she flattered me with her approbation, but by the improvements she has since made, I see she was not, at my first acquaintance, the perfect creature I thought her then... Her extraordinary understanding, lively imagination and human disposition, which soon became conspicuous, at last reconciled my father to her, and he never after debarred me the pleasure of seeing her ...[19]

Eaves and Kimpel, in their monumental biography of Samuel Richardson, describe Chapone as 'moralistic',[20] 'pious, earnest, verbose, and rather gushing'.[21] Orr calls her 'vivacious'.[14]

Intellectual circle

Chapone's friends and correspondents included George Ballard and Samuel Richardson.[18] She reviewed Ballard's manuscripts of Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain (1752), his biographical encyclopedia of women, and helped him find financial support for the project.[11][22] Chapone also introduced Ballard to the works of Mary Astell,[23] whom she had read for many years.[24] Together, Chapone and Ballard worked to find Elizabeth Elstob, who by the 1730s was living in poverty, financial assistance and a better living situation.[25][26]

Chapone struck up a correspondence with Richardson in 1750.[21] Their relationship was 'almost purely epistolary'.[21] Richardson had a high regard for Chapone,[27] calling her 'a great Championess for her Sex'.[23] In their numerous letters, they discuss Richardson's novel Clarissa and Chapone's views about the place of women in society.

Chapone objected to certain elements of Clarissa in her letters to Richardson. Eaves and Kimpel note that 'Mrs. Chapone … though generally admiring [of Clarissa], found the heroine short of her feminist ideal—she is too submissive to her father'.[28] She argued that Clarissa ought to have sought legal remedies against her father Mr Harlowe, who forces her to marry Robert Solmes against her will.[29][lower-alpha 3]

As quoted in a letter of Richardson to Chapone, Chapone wrote:

A Parent is doubtless at Liberty to with-hold his Substance from a Child who at any Age, shall marry against his Consent … But he has no Authority to compel or command a Child at any Age to marry against his or her own.[30]

Works

Hardships

Although Chapone's Hardships (1735) was published anonymously, it was an 'open secret' at the time—and recent scholarship has confirmed[23]—that she was the author.[31] The treatise discusses coverture and argues that the legal situation of English women at the time was comparable to slavery.[32]

Remarks

Chapone wrote her Remarks on Mrs. Muilman's[lower-alpha 4] Letter to the Right Honourable the Earl of Chesterfield (1750) in response to Teresia Constantia Phillips's A Letter Humbly Addressed to the Right Honourable the Earl of Chesterfield (1750).

Phillips's Letter was published following her earlier work An Apology for the Conduct of Mrs Teresia Constantia Phillips (1748).[33] In the Apology, Phillips, known by that time as a courtesan, argues that she has now rejected such a life.[34] The Letter was printed with the second edition of the Apology, published in 1750.[34] Addressed to Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, it argues that Stanhope, as a man, was able to overcome the libertinism of his youth; but that Phillips, as a woman, could not escape her past in the view of the public.[35]

Chapone's Remarks was published anonymously in 1750,[36] but Chapone told Richardson privately that she had written it.[37] Indeed, Richardson read a manuscript version of this work and may have printed it in 1750.[21] It is not clear why Chapone decided to publish her Remarks on Phillips's Letter.[38]

In her Remarks, Chapone expresses sympathy for Phillips's painful past—the Apology tells the story of Phillips's rape at age 13[39]—but argues that Phillips has not sufficiently reformed her character or shown appropriate contrition.[38][40] She further accuses Phillips of attempting to profit from Stanhope's reputation in addressing the Letter to him.[41]

Notes

- 'Mrs Chapone' is also a common designation of Hester Chapone, Sarah's daughter-in-law through her son John.

- Delany also nicknamed Chapone 'Deborah' and 'Varanese'. Orr 2016, p. 98.

- For a discussion of Mr Harlowe's role in Clarissa, see Stuber, Florian (1985). "On Fathers and Authority in Clarissa". Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900. 25 (3): 557–574. doi:10.2307/450496. JSTOR 450496..

- Teresia Constantia Phillips was married to Henry Muilman; Chapone refers to her by her married name. See Brown, Susan; Clements, Patricia; Grundy, Isobel, eds. (2006). "Teresia Constantia Phillips". Orlando: Women's Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Online.

References

- Richetti 2017, pp. 3–4.

- Harper, Douglas. "feminist". Online Etymology Dictionary.; Harper, Douglas. "feminism". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Broad 2015, p. 78.

- Bodek 1976, pp. 187, 193.

- Perry 1985, p. 21: Perry argues that Chapone was a bluestocking.

- Carroll 1964, p. 25: '… Mrs. Chapone was not a bluestocking or a sophisticate of the West End …'

- Eaves & Kimpel 1971, p. 343: Chapone and a number of Samuel Richardson's other women acquaintances were, according to Eaves and Kimpel, 'all to a greater or lesser degree bluestockings'.

- Orr 2016, p. 94.

- Hannan 2014, p. 310.

- Orr 2016, p. 95.

- "Chapone [Capon; née Kirkham], Sarah (1699–1764), author". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39723. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Orr 2016, p. 95–96.

- University of Oxford. "The Correspondence of Sarah Chapone (30 letters)". Bodleian Library. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Orr 2016, p. 97.

- Hannan 2014, p. 304.

- Hannan 2014, pp. 305–306: 'Sarah Chapone, supporting a large family on a clergyman's wages, had the most strained household income, which made large sheets of gilt-edged paper a luxury, and, for the most part, her letters appeared on smaller pages of rougher quality'.

- Orr 2016, p. 92.

- Broad 2015, p. 79.

- Delany 1861, pp. 15–16.

- Eaves & Kimpel 1971, p. 179, 277: '[Richardson] did not ... approve of [Laetitia Pilkington's] Memoirs (at least when writing to the moralistic Mrs. Chapone)'

- Eaves & Kimpel 1971, p. 351.

- Perry 1985, p. 40–41.

- Brown, Susan; Clements, Patricia; Grundy, Isobel, eds. (2006). "Sarah Chapone". Orlando: Women's Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Online.

- Orr 2016, p. 96.

- Hannan 2014, p. 302: 'It was George Ballard himself who introduced Sarah Chapone and Elizabeth Elstob in the mid 1730s, at which point Chapone began to campaign for Elstob's financial relief on account of her reduced situation in life and the deleterious effect this had on her intellectual work'.

- Perry 1985, p. 23.

- Carroll 1964, p. 25–26.

- Eaves & Kimpel 1971, p. 288.

- Brophy 1991, p. 83: 'Sarah Chapone undoubtedly realized that a suit brought by an underage daughter against her father to gain financial independence … would have almost no chance of succeeding. She was adamant, however, in insisting that in principle litigation was the only defensible course for Clarissa'.

- Letter of Samuel Richardson to Sarah Chapone, 2 March 1752. Carroll 1964, p. 204.

- Hannan 2014, p. 308.

- Chapone 1735, p. 4: '… the Estate of Wives is more disadvantagious [sic] than Slavery itself'.

- Flynn, Carol Houlihan (2014). Samuel Richardson: A Man of Letters. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4008-5404-2. OCLC 884013517.

- Orr 2016, p. 105.

- Orr 2016, p. 106.

- Glover 2018, p. 7.

- Orr 2016, p. 104.

- Glover 2018, p. 16.

- Flynn, Carol Houlihan (2014) [1982]. Samuel Richardson: A Man of Letters. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4008-5404-2. OCLC 884013517.

- Orr 2016, p. 106–107.

- Thompson, Lynda M. (2000). The scandalous Memoirists: Constantia Phillips and Laetitia Pilkington and the Shame of 'Publick Fame'. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-7190-5573-3. OCLC 43427898.

Bibliography

- Bodek, Evelyn Gordon (1976). "Salonières and Bluestockings: Educated Obsolescence and Germinating Feminism". Feminist Studies. 3 (3/4): 185–199. doi:10.2307/3177736. JSTOR 3177736.

- Broad, Jacqueline (January 2015). ""A Great Championess for Her Sex": Sarah Chapone on Liberty as Nondomination and Self-Mastery". The Monist. 98 (1): 77–88. doi:10.1093/monist/onu009. ISSN 0026-9662. JSTOR 44012715.

- Brophy, Elizabeth Bergen (1991). Women's Lives and the 18th-Century English Novel. Tampa: University of South Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-1036-5. OCLC 22422353.

- Carroll, John, ed. (1964). Selected Letters of Samuel Richardson. Oxford: Clarendon Press – via Internet Archive.

- Chapone, Sarah (1735). The Hardships of the English Laws in Relation to Wives. London: William Bowyer and J. Roberts.

- Delany, Mary (1861). Lady Llanover (ed.). The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany. 1. London: Richard Bentley. OCLC 1016238532.

- Eaves, T. C. Duncan; Kimpel, Ben (1971). Samuel Richardson: A Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 31889992 – via Internet Archive.

- Glover, Susan (19 January 2018). "Introduction". In Glover, Susan Paterson (ed.). The Hardships of the English Laws in Relation to Wives. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315557328. ISBN 978-1-315-55732-8.

- Hannan, Leonie (3 July 2014). "Collaborative Scholarship on the Margins: An Epistolary Network". Women's Writing. 21 (3): 290–315. doi:10.1080/09699082.2014.925031. ISSN 0969-9082.

- Harris, Jocelyn (September 2012). "Philosophy and Sexual Politics in Mary Astell and Samuel Richardson". Intellectual History Review. 22 (3): 445–463. doi:10.1080/17496977.2012.695198. ISSN 1749-6977.

- Orr, Clarissa Campbell (3 March 2016). "The Sappho of Gloucestershire: Sarah Chapone and Christian Feminism". In Heller, Deborah (ed.). Bluestockings Now!: The Evolution of a Social Role. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315569581. ISBN 978-1-315-56958-1.

- Perry, Ruth (1985). "Introduction". In Perry, Ruth (ed.). Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1747-2. OCLC 10779597.

- Richetti, John J. (2017). A History of Eighteenth-Century British Literature. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781119083436. ISBN 978-1-119-08213-2. OCLC 990778262.

Further reading

- Chapone, Sarah (19 January 2018) [1735]. Glover, Susan Paterson (ed.). The Hardships of the English Laws in Relation to Wives. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315557328. ISBN 978-1-315-55732-8. A recent scholarly edition of Chapone's Hardships, including contemporary responses and criticism, as well as the Remarks.

- Eaves, T. C. Duncan; Kimpel, Ben (1971). Samuel Richardson: A Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 351–354. OCLC 31889992 – via Internet Archive. An opinionated but comprehensive account of Chapone's relationship with Richardson.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Sarah Chapone |