Augusta Hall, Baroness Llanover

Augusta Hall, Baroness Llanover (21 March 1802 – 17 January 1896), born Augusta Waddington, was a Welsh heiress, best known as a patron of the Welsh arts.

Early life

She was born near Abergavenny, the youngest daughter of Benjamin Waddington of Ty Uchaf, Llanover and his wife, Georgina Port. She was the heiress to the Llanover estate in Monmouthshire.[1]

Marriage

In 1823, Augusta became the wife of Benjamin Hall. Their marriage joined the large South Wales estates of Llanover and Abercarn.

Hall (1802–1867, after whom "Big Ben" is said to have been named, as he was Commissioner of Works in 1855 when it was built), was for some years Member of Parliament for Monmouth, but transferred to a London seat just prior to the Newport Rising which brought with it a turbulent time in Monmouthshire. He was created a baronet in 1838, and entered the House of Lords in 1859 under Prime Minister Palmerston as Baron Llanover. However, his wife overshadowed him in life and subsequent reputation.

Llanover Hall

In 1828, the couple commissioned Thomas Hopper to build Llanover Hall for them. It was designed as a kind of arts centre as well as a family home.

Lady Llanover had always been interested in Celtic Studies. Her sister, Frances, had previously married a German ambassador to Great Britain, Baron Bunsen, whose social circle was also interested in Celtic subjects and culture.

Lady Llanover was greatly influenced by the local bard, Thomas Price, whom she met at a local Eisteddfod in 1826. Carnhuanawc taught her the Welsh language; she took the bardic name "Gwenynen Gwent", ('the bee of Gwent'). She became an early member of Cymreigyddion y Fenni. Her Welsh was never considered fluent but she was an extremely enthusiastic proponent of all things Welsh. She structured her household at Llanover Hall on what she considered to be Welsh traditions and gave all her staff Welsh titles and Welsh costume to wear.

Her husband shared her concern for the preservation of the heritage of Wales, and campaigned for the Welsh to be able to hear church services conducted in the Welsh language.

'Welsh Costume'

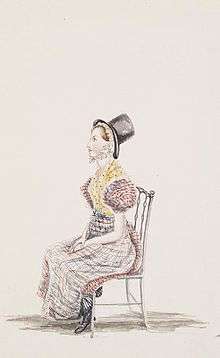

At the Cardiff Eisteddfod of 1834, she won first prize for her essay on The Advantages resulting from the Preservation of the Welsh language and National Costume of Wales which was published in Welsh and English in 1836.[2] She probably commissioned a series of watercolours of Welsh costumes which illustrate costumes worn by women in south Wales and Cardiganshire, 13 of which were reproduced as hand-coloured prints soon after 1834 (but were not published with the essay). These were little more than fashion prints for herself and friends to create dresses for themselves and their servants to be worn on special occasions, especially fancy dress balls. Although she was keen to see the women of Wales dressed in home-spun Welsh wool rather than the light cheap cottons which were becoming popular by the 1830s, there is very little evidence to show that she had any influence on the wearing of Welsh costume other than by her servants, family and friends, and there is no firm evidence to suggest that she influenced what was later adopted as the national costume of Wales.[3][4] She did encourage the production of traditional stripes and checks in woollen cloth and offered prizes for good examples of these at Eisteddfodau, but there were few entrants, with the weaver of Gwenfrwd mill, on her own estate, taking many of the prizes.[5]

Other achievements

In 1850, she helped found Y Gymraes ("The Welshwoman"), the first Welsh-language periodical for women. Her other interests included cookery ('The First Principles of Good Cookery' published in 1867) and folk music; she encouraged the production and use of the traditional Welsh triple harp, employing a resident harpist at Llanover Hall.

She was a patron of the Welsh Manuscripts Society, of the Welsh Collegiate Institution at Llandovery, funded the compilation of a Welsh dictionary by Daniel Silvan Evans. She bought Welsh manuscripts of Taliesin Williams, Taliesin ab Iolo and the collection of Iolo Morganwg (Edward Williams) (now held in the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff).

She collaborated with Welsh musicians such as Maria Jane Williams, a noted harpist, vocalist and guitar player and Henry Brinley Richards, a noted composer best known for writing "God Bless the Prince of Wales", and herself produced a Collection of Welsh Airs.

Temperance movement

Another main interest of hers was the temperance movement to which end she closed all the public houses on her estate, sometimes opening a modest temperance inn in their place, such as Y Seren Gobaith ('the Star of Hope') temperance inn, which replaced the Red Lion at Llanellen. She was an outspoken and lifelong critic of the evils of alcohol. Closely associated with her temperance work was religion in the form of militant Protestantism and she endowed two Calvinistic Methodist churches in the Abercarn area, with services conducted in the Welsh language, but a liturgy based on the Book of Common Prayer.

She outlived her husband by nearly thirty years, living well into her nineties. Only one of their daughters survived to adulthood: Augusta, who in 1846 married Arthur Jones of Llanarth, of an old Roman Catholic family. Their son, Ivor Herbert, 1st Baron Treowen, became a Major-General during the First World War.

References

- Marion Löffler. "Hall, Augusta, Lady Llanover ('Gwenynen Gwent') (1802-1896), patron of Welsh culture and inventor of the Welsh national costume". Dictionary of Wales Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- from Michael Freeman's Welsh Costume web site

- Michael Freeman, 'Lady Llanover and the Welsh Costume Prints', The National Library of Wales Journal, xxxiv, no 2 2007, pp.235–251.

- Welsh National Dress Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine from St Fagans National History Museum website

- from Michael Freeman's Welsh Costume web site