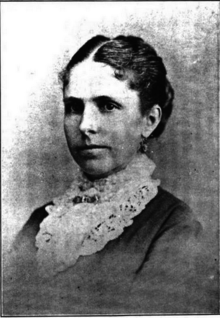

Sarah Carmichael Harrell

Sarah Carmichael Harrell (pen name, Citizen; January 8, 1844 – 1929) was an American educator, social reformer, and writer. She served two years as superintendent of the department of scientific temperance in the public schools,[1] and was the "first female teacher to receive pay equal with male teachers in southeast Indiana".[2] Harrell was a member of the Indiana Board of World's Fair Managers in connection with the World's Columbian Exposition.

Sarah Carmichael Harrell | |

|---|---|

"A woman of the century" | |

| Born | 1846 Aurora, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | March 21, 1893 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Pen name | Citizen |

| Occupation | educator, temperance reformer, writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Brookville College |

| Subject | floriculture, education, letters of travel |

| Spouse | Samuel Sidney Harrell ( m. 1871) |

| Children | Hallie, Edna |

Early years and education

Sarah Carmichael was born in Brookville, Indiana, January 8, 1844.[3] Noah Carmichael, her father, was born in Tennessee, and came to Franklin County, Indiana early in its history, being a pioneer merchant and stock dealer of the county seat. In Franklin County, he married Edith Stoops (born in Brookville). William Stoops (born in Kentucky), the father of Edith Stoops, became connected with the agricultural interests of Franklin County early in its history.[4]

Harrell entered the primary class in Brookville College when eight years of age, and while still in the intermediate class, she left college to start teaching at her first school.[3]

Career

Educator

In 1859, Harrell began to teach in the public schools of Indiana, and did so for twelve years, being the first woman teacher to receive equal wages with male teachers in southeast Indiana.[3]

Because of her continued interest in education, she took a complete course with the Chautauqua Reading Circle and received about 25 seals for post-graduate work. During her husband's eight years' service in the Indiana General Assembly, she formed an extended acquaintance among prominent people of the state, and was frequently called upon to fill positions requiring ability and foresight.[4] Besides these positions, she served as superintendent of scientific temperance instruction for Indiana, and prepared to secure the enactment of a law to regulate the study of temperance in the public schools.[3]

In 1891, Harrell was appointed by Governor Alvin Peterson Hovey as a member of Indiana's Columbian Exposition board. She was made a member of the committee on education and woman's work, but gave most of her time and energy to the former. As secretary of the educational committee, she worked almost day and night for two years, preparing a literary and educational exhibit of the state.[4] Her greatest work was the origination and carrying to a successful completion of the plan known as the "Penny School Collection Fund of Indiana", used in the educational exhibit in the Columbian Exposition.[3]

As a member of Indiana's Board of World's Fair Managers, she immediately set to devise some means to create an interest among the teachers and school children of Indiana in the Columbian Exposition. The Penny Fund scheme was the result. She presented her plans to the Franklin County Teachers' Institute where it was endorsed, and action immediately taken to cooperate with her. With like assurance from teachers, school officers and others, the matter was taken before the Indiana Board of World's Fair Managers, where it was favorably considered, and Harrell was appointed to develop the plan, with instructions to consult with State Superintendent Hervey D. Vories, W. A. Bell, of the Indiana School Journal, and L. H. Jones, Superintendent of Indianapolis city schools. Accordingly, within a few weeks time, 18,000 circulars, "Indiana Schools in the World's Fair," were distributed to teachers, school officials and the press of the State. This circular suggested two "Exposition Days" to be given up to patriotic and historical exercises in all the schools of the State, at which time a collection of US$0.01 from the children, US$0.10 from teachers, US$0.25 from high school principals, and US$0.50 from the city and town school superintendents, school boards and township trustees would be taken.[5]

Other pursuits

Under various pen names, Harrell wrote articles on floriculture, education, and letters of travel.[3] She was a frequent contributor to floral and household magazines, and educational journals. However, she disclaimed any ambition in the way of authorship. A contemporaneous biographer said of her: "Over the signature of 'Citizen' at the age of sixteen, she (Mrs. Harrell) furnished a series of letters to the local press, showing up the management of the liquor traffic, the boldness of so-called moral and religious men who are its patrons. Her letters had such an awakening effect as to the evil influence of liquor that they created more agitation than had been stirred up for years." The circular letters of Harrell, which she sent out while preparing the exhibit of the state for the Columbian Exposition, brought favorable comments. She wrote articles on scientific temperance and education which were considered models of clear and comprehensive English.[4]

Harrell was also an active worker in the church and took a keen interest in the welfare of young people. One of her public labors was the opening of a reading room in Brookville for the use of the boys of the town. Later, she was also instrumental in securing the Carnegie library for Brookville, and still later, became identified with charity work in the county.[4]

Personal life

She married Samuel Sidney Harrell on December 18, 1871. They had two daughters, Hallie and Edna, the former being a graduate of DePauw University.[4][3]

References

- Herringshaw 1914, p. 474.

- Carroll 2010, p. 146.

- Willard 1893, p. 358.

- Reifel 1915, p. 689-.

- Campbell 1892, p. 81.

Attribution

Bibliography

- Carroll, Peter N. (1 November 2010). Keeping Time: Memory, Nostalgia, and the Art of History. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3792-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)