Sao Saimong

Sao Sāimöng or Sao Sāimöng Mangrāi (13 November 1913 – 14 July 1987) was a member of the princely family of Kengtung State. He was a government minister in Burma (now Myanmar) soon after independence; he was also a scholar, historian and linguist. His wife, Mi Mi Khaing, was also a scholar and writer.

Sao Saimong | |

|---|---|

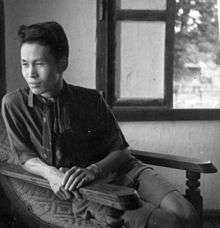

Sao Saimong in his youth | |

| Born | 13 November 1913 |

| Died | 14 July 1987 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | Burmese |

| Other names | Sao Sāimöng Mangrāi |

| Alma mater | Rangoon University University of London |

| Occupation | Government minister |

| Known for | Reformed the Shan script |

| Spouse(s) | Mi Mi Khaing |

| Children | Yin Yin Nwe among others... |

| Parent(s) | Kawng Kiao Intaleng Nang Daeng |

Biography

Sao Saimong was the first son of the fourth wife, Nang Daeng, of Saopha Kawng Kiao Intaleng (who had succeeded as ruler of Kengtung in 1895). Early in his life, Sao Saimong was sent to Bangkok to become a novice monk at the Wat Thepsirin in Bangkok, since it was his father's hope that he would eventually become the chief abbot of Kengtung. In the 1920s Sao Konkaeu Intaleng attended a durbar in India, and realized that all of his sons should be given a western education to be successful, so Sao Saimong was called back from Bangkok and sent to the Shan Chiefs' School in Taunggyi, a school founded by the British administration to train the sons of ruling families. From there, he went on to attend Rangoon University, and then on to the University of London. Returning to Burma in 1940 during the start of the Second World War, he was soon swept into war to serve with the British army. He was evacuated to India, and returned to Burma soon after the war. Several of his elder brothers were boys and Sao Saimong had not expected to rule Kengtung. But he did so briefly on his return from India, since the heir apparent, his nephew, Sao Sai Long, had not yet finished his studies in Australia.

In 1947, after the Shan principalities agreed to become part of the Union of Burma, Sao Saimong had an administrative career in independent Burma and was Chief Education Officer for Shan and Kayah States. He was instrumental in the design of the revised script for Shan.[1]

Like most of the other former rulers of the Shan States, Sao Saimong was imprisoned when General Ne Win took power in 1962. After six years in prison he was released in 1968. After his release, he settled in Taunggyi, and in 1969 he was ordained as a monk in one of the Kengtung monasteries. In his scholarly career he was invited to Cornell University, the University of Michigan and Wolfson College, Cambridge. At Cambridge University Library, in 1982 and 1983, he worked with Wilfrid Lockwood and Andrew Dalby on the Scott Collection, formed by J. G. Scott, British administrator in the Shan States, whose activities he had already chronicled in his 1969 publication The Shan States and the British Annexation.

Although it is neither compulsory nor customary in Myanmar to take a surname, the family chose the surname Mangrāi after the medieval king Mangrai of Chiangmai (northern Thailand), traditional founder of Kengtung, from whom they trace their descent; this surname therefore appears on Sao Saimong's later publications.

Published works

- The Shan States and the British Annexation. Cornell University, Cornell, 1965; 2nd ed., 1969

- The Pādaeng Chronicle and the Jengtung State Chronicle Translated. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1981

Sources

- Tzamg Yawnghwe (1987). The Shan of Burma: Memoirs of a Shan Exile. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 223. ISBN 9789971988623.

- Sao Sāimöng Mangrāi, The Pādaeng Chronicle and the Jengtung State Chronicle Translated, p. 278

- The Guardian [Rangoon], 16 July 1987