Sante Kimes

Sante Kimes (born Sante Singhrs; July 24, 1934 – May 19, 2014)[4] was an American criminal who was convicted of two murders, as well as robbery, forgery, violation of anti-slavery laws, and numerous other crimes. Many of these crimes were committed with the assistance of her son, Kenny Kimes. They were tried and convicted together for the murder of Mrs. Irene Silverman, along with 117 other charges.

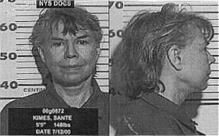

Sante Kimes | |

|---|---|

NYS DOCS mugshot (2000) | |

| Born | July 24, 1934 |

| Died | May 19, 2014 (aged 79) |

| Cause of death | Natural causes |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Con artist |

| Spouse(s) | Ed Walker (1957–1969; divorced)[3] Kenneth Kimes (died 1994; disputed as to whether they ever legally were married)[4][4] |

| Children | Kenneth Karam Kimes (born 1975) Kent Walker (born 1962 or 1963[5] [4]) |

| Motive | Financial |

| Conviction(s) | Murder, 2 counts, robbery, slavery, forgery, over 100 other charges |

| Criminal penalty | Life in prison, New York State; Life in prison, California |

Kenny made a plea deal in the murder of David Kazdin, pleading guilty and agreeing to testify against his mother in her trial for Kazdin's murder in return for her not facing a death sentence. Sante Kimes was subsequently convicted of that murder. The pair were also suspected but never charged in a third murder in the Bahamas, to which Kenny Kimes confessed.

Early life

According to court records, Sante Kimes was born Sante Singhrs in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, one of four children of Mary Van Horn, a native of Illinois and of partial Dutch descent, and Prama Mahendra Singhrs (1889–1940),[6] who was East Indian and came to the United States through Canada.

Sante Kimes gave numerous conflicting stories about her origins and numerous other accounts are difficult to confirm.[7] Her son, Kent Walker, has said that her birth certificate might be forged.[8] Walker, in his book Son of a Grifter, has reported a claim by an old acquaintance of his mother that Kimes was the daughter of a respectable family who was unable to cope with her aberrant, wild antics. Kimes herself has claimed that her father was a laborer and that her mother was a prostitute who migrated to Los Angeles during the Dust Bowl, where the young Kimes ran wild in the streets.

Kimes attended high school in Carson City, Nevada, and graduated in 1952.[9] She soon married a high school boyfriend, but the marriage lasted only three months. In 1956, Kimes reunited with another sweetheart from high school, Edward Walker. They married in 1957 and had one son, Kent. After a shoplifting conviction in 1961, Kimes separated and reconciled intermittently with Walker but their divorce was not finalized until 1969.[4]

In 1971, she met motel tycoon Kenneth Kimes. Usually reported as having married, questions exist as to whether the couple ever legally tied the knot.[10] They had one son, Kenneth Karam Kimes (born 1975). [4]

Criminal behavior

Sante Kimes spent the better part of her life fleecing people of money, expensive merchandise, and real estate, either through elaborate con games, arson, forgery, or outright theft.[7] According to Kent Walker, she committed insurance fraud on numerous occasions, frequently by committing arson and then collecting money for property damage. Kimes delighted in introducing her husband Kenneth as an ambassador, a ploy that even gained the couple access to a White House reception during the Ford administration, and would sometimes even impersonate Elizabeth Taylor, whom she resembled slightly.

Walker also alleges that Kimes committed many acts of fraud that were not even financially necessary, such as enslaving maids when she could easily afford to pay them.[11] Kimes frequently offered young, homeless illegal immigrants housing and employment, then kept them as virtual prisoners by threatening to report them to the authorities if they didn't follow her orders.[12] As a result, she and Kenneth spent years squandering his fortune on lawyers' fees, defending themselves against charges of slavery. Kimes was eventually arrested in August 1985 and was sentenced by the U.S. District Court to five years in prison for violating federal anti-slavery laws and was successfully sued by Honolulu civil attorney David Schutter in civil court.[13] Kenneth took a plea bargain and agreed to complete an alcohol treatment program. He and their son Kenny lived a somewhat normal life until Kimes was released from prison in 1989. Kenneth died in 1994.

Sante and Kenny were suspects in the 1995 abduction of 62 year-old Levitz Furniture heiress Jacqueline Levitz from her home in Vicksburg, Mississippi until a July 1998 announcement by the FBI that its investigations had concluded that, "There is nothing that would indicate that [they] had anything to do with Ms. Levitz."[14]

Murders

David Kazdin

David Kazdin had allowed Kimes to use his name on the deed of a home in Las Vegas that was actually occupied by Kimes and her husband Kenneth in the 1970s. Several years later, Kimes convinced a notary to forge Kazdin's signature on an application for a loan of $280,000, with the house as collateral. When Kazdin discovered the forgery through a letter sent from his commercial bank and threatened to expose Kimes, she ordered him killed.[15]

On March 9, 1998, Kenny murdered Kazdin in his Los Angeles home by shooting him in the back of the head. According to another accomplice's later testimony, all three participated in disposing of the evidence. Kazdin's body was found in a dumpster near Los Angeles airport in March 1998. The murder weapon was never recovered, having been disassembled and dropped into a storm sewer.[15]

Irene Silverman

In June 1998, Kimes and Kenny perpetrated a scheme whereby she would assume the identity of their landlady, 82-year-old socialite Irene Silverman, and then appropriate ownership of her $7.7 million Manhattan mansion.[16] The pair began renting a room in Silverman's mansion in June 1998 before she was reported missing on July 5. The search for Ms. Silverman went as far as Mount Olive, New Jersey. Despite the fact that Silverman's body was never found, both mother and son were convicted of murder in 2000, in no small part because of the discovery of Kimes' notebooks detailing the crime and notes written by Silverman, who was extremely suspicious of the pair. Among other things the two suspects kept casually asking Silverman for her ID and Social Security number, looked away from security cameras in the building lobby as they walked past, and repeatedly refused to let housekeepers into their rented room for cleaning.

During the trial for the Kazdin murder, Kenny confessed that after his mother had used a stun gun on Silverman, he strangled her, stuffed her corpse into a bag and deposited it in a dumpster in Hoboken, New Jersey.[17]

Sayed Bilal Ahmed

Kenny also confessed to murdering a third man, banker Sayed Bilal Ahmed, at his mother's behest in The Bahamas in 1996,[18] which had been suspected by Bahamian authorities at the time.[19] Kenny testified that the two acted together to drug Ahmed, drown him in a bathtub, and dump his body offshore,[20] but no charges were ever filed in that case.

Kimes denied any involvement in or knowledge of the murders, and she claimed that Kenny confessed solely to avoid receiving the death penalty.[21]

Investigation and Arrest

The investigation into the Kimeses began officially on March 14, 1998, when Kazdin's remains were found in a dumpster near LAX. The FBI and LAPD detectives assigned to the investigation focused on the mortgage loan application with the forged signature that falsely linked Kazdin to a house in Las Vegas which had been partly burned down in an attempted arson. The supposed homeowner turned out to be David McCarran, a homeless man who said Kimes and Kenny had lit the arson fire. He also claimed to have been forced to stay in the house by the Kimeses, who hoped to collect the insurance money from the loss of the house.

Investigators also located James Patterson, a second man who confessed to selling a handgun to Kenny which he used to kill Kazdin. He was told of several potential felony charges stemming from the murder and mortgage fraud and reluctantly agreed to cooperate with the police in apprehending the pair to avoid prosecution.

At the end of June 1998, Patterson got a call from Kimes about an expensive townhouse in New York's Upper West Side she wanted to sell for $7.7 million (the building owned by Silverman), and she need his help with the paperwork. Patterson agreed to meet her in New York on July 5; he informed the FBI about the scheduled meeting before he left on July 3. Two days later, Patterson met Kimes at the New York Hilton around 6 p.m. that evening. Around 7 p.m., Kenny arrived at the Hilton and approached Kimes; upon his appearance FBI and NYPD officers quickly moved in to arrest both of them.

The Kimeses had stolen a black Lincoln Town Car from a rental car dealership in Utah the previous May using a bounced check. When the police found the vehicle in the following day on July 6, they searched it and found what one officer called a "treasure chest" full of evidence: a stun gun case, forged Social Security cards, two hand guns, a pair of handcuffs, a folder full of various forms and applications related to Silverman's mansion, and a set of fifteen notebooks on which Sante had written detailed descriptions of mortgage fraud schemes involving many intended victims including both Silverman and Kazdin.

Trials

Although the Kazdin murder occurred first, the Kimeses were tried in New York City first for the Silverman murder. Evidence recovered from their car helped establish the case for trying them for Kazdin's murder as well.[22]

The Silverman trial was unusual in many aspects, namely the rare combination of a mother/son team and the fact that no body was ever recovered. Nonetheless, the jury was unanimous in voting to convict them not only of murder but of 117 other charges including robbery, burglary, conspiracy, grand larceny, illegal weapons possession, forgery and eavesdropping on their first poll on the subject.[23]

The judge also took the unusual step of ordering Kimes not to speak to the media even after the jury had been sequestered, as a result of her passing a note to New York Times reporter David Rhode in court. The judge threatened to have Kimes handcuffed during further court appearances if she persisted and restricted her telephone access to calls to her lawyers. The judge contended that Kimes was attempting to influence the jury as they may have seen or heard any such interviews, and that there would be no cross-examination as there would be in court. Kimes had earlier chosen to not take the stand in her own defense after the judge ruled that prosecutors could question her about the previous conviction on slavery charges.[24]

During the sentencing portion of the Silverman trial, Kimes made a prolonged statement to the court blaming the authorities, including their own lawyers, for framing them. She went on to compare their trial to the Salem Witch Trials and claimed that the prosecutors were guilty of "murdering the Constitution" before the judge told her to be quiet. When the statement was concluded, the presiding judge responded that Kimes was a sociopath and a degenerate and her son was a dupe and a "remorseless predator" before imposing the maximum sentence on both of them.[25] This amounted to 120 years for Sante and 124 years for her son Kenny, effectively sentencing both of them to life in prison.

In October 2000, while doing an interview, Kenny held Court TV reporter Maria Zone hostage by pressing a ballpoint pen into her throat. Zone had interviewed Kimes once before without incident.[26] Kenny's demand was that his mother not be extradited to California, where the two faced the death penalty for the murder of Kazdin. After four hours of negotiation, Kenny removed the pen from Zone's throat. Negotiators created a distraction which allowed them to quickly remove Zone and wrestle Kimes to the ground.

In March 2001, Kenny was extradited to Los Angeles to stand trial for the murder of Kazdin. Kimes was extradited to Los Angeles in June 2001. During that trial in June 2004, while he was facing the death penalty, Kenny changed his plea from "not guilty" to "guilty" and implicated his mother in the murder in exchange for a plea deal that his mother should not receive the death penalty if convicted. Kenny then testified in trial against his mother, exposing every detail about their multiple crimes and describing how she indoctrinated him into becoming her accomplice. Kimes again made a prolonged statement denying the murders and accusing police and prosecutors of various kinds of misconduct, and she was again eventually ordered by the presiding judge to be silent.[27] The sentencing judge in the Kazdin case called Mrs. Kimes "one of the most evil individuals" she had met in her time as a judge.[28]

Imprisonment and death

Kimes was serving a life sentence plus 125 years at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women in New York, where she died on May 19, 2014.[29] Additionally, she and her son were each sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of Kazdin in California. Kenny is currently incarcerated at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility in California.

In media

A 2001 made-for-TV movie, Like Mother, Like Son: The Strange Story of Sante and Kenny Kimes, starred Mary Tyler Moore as Kimes, Gabriel Olds as Kenny, and Jean Stapleton as Silverman. In 2006, another television movie based on a book about the case, A Little Thing Called Murder, starring Judy Davis and Jonathan Jackson, aired on Lifetime.

Kimes was also featured in a 2009 episode of the television show Dateline[30] and a 2015 episode of Diabolical Women.[31]

References

- ref>https://books.google.com/books/about/Dead_end.html?id=uMIuAQAAIAAJ

- "Sante Kimes". biography.com. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- "He Said 'No'". PEOPLE.com.

- King, Jeanne (July 10, 2002). "Dead End: The Crime Story of the Decade : Murder, Incest, and High-tech Thievery". M. Evans – via Google Books.

- King, Jeanne (March 20, 2002). "Dead End: The Crime Story of the Decade—Murder, Incest and High-Tech Thievery". M. Evans – via Google Books.

- Newspaper obituary of Sante Kimes's father, findagrave.com; accessed July 8, 2010.

- McFadden, Robert (July 14, 1998). "A FAMILY PORTRAIT: A special report.; A Twisted Tale of Deceit, Fraud and Violence". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- Walker, Kent; Schone, Mark (2001). Son of a Grifter. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 15–19. ISBN 978-0060188658. OCLC 46343316.

- Havill, Adrian. "Mother and Son Murder Team: Sante and Kenny Kimes". Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Andrews, Suzanna. "The Story of Sante Kimes: Mother, Murderer, and Criminal Mastermind". Vanity Fair.

- Plotz, David (2001-05-20). "Take a Son to Work David Plotz, The New York Times 5/20/2001". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- Cohen, Adam (1998-07-20). "The Landlady Vanishes". Time. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- "Woman convicted in isle slavery held in N.Y. missing-person case". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 1998-07-11. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Police: Mom, Son Not Tied To Levitz Disappearance". articles.sun-sentinel.com. Sun-Sentinel. 29 July 1998. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "Mother-Son Duo Faces Day in L.A. Court; Law: The pair who killed a New York socialite will be tried in the 1998 slaying of a local man. Anna Gorman, Los Angeles Times, 6/26/2002". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. 2002-06-26. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- The Lady Vanishes, alixkirsta.com 1999-11-20. Retrieved 2014-02-10

- "Murderer Reveals New Details In Slaying of Socialite in 1998 Thomas J. Luek, The New York Times, 6/24/2004". Nytimes.com. 2004-06-24. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- Kimes, Son Get Life Sentence in L.A. Murder (washingtonpost.com) Kimes, Son Get Life Sentence in L.A. Murder Reuters/Washington Post 3/22/2005]

- "Suspects in a Disappearance Have Been Running for Years The New York Times, 7-10-1998". Nytimes.com. 1998-07-10. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Associated Press/The Union Democrat, 6/23/2004". 2004-06-23. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "I loved Irene, Sante insists Michelle Caruso, New York Daily News, 7/24/2004". Nydailynews.com. 2004-06-24. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Con Artist Is Returned to L.A. for Murder Trial; Crime: He and his mother are accused of killing a local businessman. They were convicted last year of slaying a wealthy New York woman. Twlla Decker, Los Angeles Times 3/22/2001". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. 2001-03-22. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Mother and Son Guilty of Killing A Socialite Who Vanished in '98 David Rhode, The New York Times, 5/19/2000". Nytimes.com. 2000-05-19. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Sante Kimes Chastised by Judge Over Contacts With News Media David Rhode, The New York Times, 5/17/2000". Nytimes.com. 2000-05-17. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Mother and Son Are Given Life Sentences Katherine E. Finkelstein, The New York Times, 6/28/2000". Nytimes.com. 2000-06-28. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Kenneth Kimes Takes Reporter As a Hostage Shaila K. Dewan, The New York Times, 10/11/200". Nytimes.com. 2000-10-11. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Sante Kimes Denies 1998 Slaying; She says the Granada Hills victim was her 'best friend' and that she didn't order his death. Anna Gorman, Loas Angeles Times, 6/22/2004". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. 2004-06-22. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Life Terms For Pair The New York Times, 3/22/2005". New York Times. Los Angeles (Calif); New York City. 2005-03-22. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- McShane, Larry (2014-05-20). "Murder, grifting mastermind Sante Kimes dead in prison at 79". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2014-05-20.

- "DATELINE: Real Life Mysteries ~ The Grifters ~". TVGuide.com. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Season 1 Episode Guide". TV Guide. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

External links

- Sante Kimes on IMDb

- Sante and Kenneth Kimes: A Life of Crime – Court TV

- The Biography Channel – Notorious Crime Profiles Sante Kimes

- Profile from Radford University Department of Psychology

- Like Mother Like Son: The Strange Story of Sante and Kenny Kimes on IMDb

- A Little Thing Called Murder on IMDb

- Sante Kimes at Find a Grave