Sagala

Sagala, Sakala (Sanskrit: साकला), or Sangala (Ancient Greek: Σάγγαλα) was a city in ancient India,[1][2] which was the predecessor of the modern city of Sialkot that is located in what is now Pakistan's northern Punjab province.[3][4][5][6] The city was the capital of the Madra Kingdom and it was razed in 326 BC during the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great.[7] In the 2nd century BC, Sagala was made capital of the Indo-Greek kingdom by Menander I. Menander embraced Buddhism after extensive debating with a Buddhist monk, as recorded in the Buddhist text Milinda Panha.[8] Sagala became a major centre for Buddhism under his reign, and prospered as a major trading centre.[9][10]

Mahabharata

Sagala is likely the city of Sakala (Sanskrit: साकला) mentioned in the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit epic of ancient India, as occupying a similar area as Greek accounts of Sagala.[11] The city may have been inhabited by the Saka, or Scythians, from Central Asia who had migrated into the Subcontinent.[12] The city in the Mahabharata was renowned for the wild and hedonist women who lived in the forests surrounding the city.[13] The city was said to have been located in the Sakaladvipa region between the Chenab and Ravi rivers, now known as the Rechna Doab.

The city was located beside a river of the name of Apaga, and a clan of the Vahikas known by the name of the Jarttikas (Mbh 8:44). Nakula, proceeding to Sakala, the city of the Madras, made his uncle Shalya accept from affection the sway of the Pandavas (Mbh 2:31).

History

In the Mahabharata

The Mahabharata describes that, the third Pandava, Arjuna, defeats all the kings of Shakala in his Rajasuya conquest. One of the kings mentioned here is Prativindhya (not the son of Yudhishthira and Draupadi).

Indian campaign of Alexander the Great

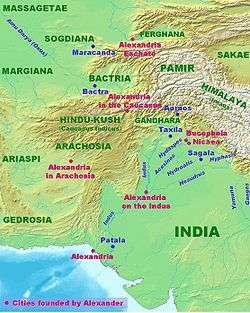

The city appears in the accounts of Alexander the Great's conquests of ancient India. After crossing the Acensines (River Chenab) Alexander, joined by Porus with elephants and 5,000 local troops, laid siege to Sagala, where the Cathaeans had entrenched themselves. The city was razed to the ground, and many of its inhabitants killed:

- "The Cathaeans... had a strong city near which they proposed to make their stand, named Sagala. (...) The next day Alexander rested his troops, and on the third advanced on Sangala, where the Cathaeans and their neighbours who had joined them were drawn up in front of the city. (...) At this point too, Porus arrived, bringing with him the rest of the elephants and some five thousand of his troops. (...) Alexander returned to Sangala, razed the city to the ground, and annexed its territory". Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, V.22-24

Sagala was rebuilt and established as an outpost and incorporated into Alexander's vast empire. It was the easternmost outpost established by Alexander and remained a center of Hellenistic influence for quite some time after.

Shunga Empire

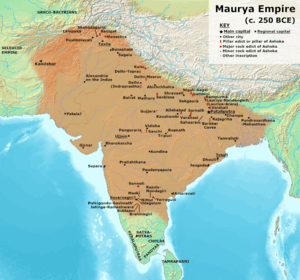

Following his overthrowing of the Mauryan Empire, Pushyamitra Shunga established the Shunga Empire and expanded northwest as far as Sagala. According to the 2nd century Ashokavadana, the king persecuted Buddhists:

- "Then King Pushyamitra equipped a fourfold army, and intending to destroy the Buddhist religion, he went to the Kukkutarama. (...) Pushyamitra therefore destroyed the sangharama, killed the monks there, and departed.

- After some time, he arrived in Sakala, and proclaimed that he would give a hundred dinara reward to whoever brought him the head of a Buddhist monk" (Shramanas) Ashokavadana, 133, trans. John Strong.

Yavana era

Sagala, renamed Euthydemia by the Greeks, was used as a capital by the Greco-Bactrian (alternatively Indo-Greek or Graeco-Indus) king Menander during his reign between 160 and 135 BC.[14]

Though many Graeco-Bactrian, and even some Indo-Greek cities were designed along Greek architectural lines. In contrast to other imperialist governments elsewhere, literary accounts suggests the Greeks and the local population of cities like Sagala lived in relative harmony, with some of the local residents adopting the responsibilities of Greek citizenship - and more astonishingly, Greeks converting to Buddhism and adopting local traditions.

The best descriptions of Sagala however, come from the Milinda Panha, a dialogue between king Menander and the Buddhist monk Nagasena. Historians like Sir Tarn believe this document was written around 100 years after Menander's rule, which is one of the best enduring testimonies of the productiveness and benevolence of his rule, which has made the more modern theory that he was regarded as a Chakravartin - King of the Wheel or literally Wheel-Turner in Sanskrit - generally accepted.

In the Milindapanha, the city is described in the following terms:

- There is in the country of the Yonakas a great centre of trade, a city that is called Sâgala, situated in a delightful country well watered and hilly, abounding in parks and gardens and groves and lakes and tanks, a paradise of rivers and mountains and woods. Wise architects have laid it out, and its people know of no oppression, since all their enemies and adversaries have been put down. Brave is its defence, with many and various strong towers and ramparts, with superb gates and entrance archways; and with the royal citadel in its midst, white walled and deeply moated. Well laid out are its streets, squares, cross roads, and market places. Well displayed are the innumerable sorts of costly merchandise with which its shops are filled. It is richly adorned with hundreds of alms-halls of various kinds; and splendid with hundreds of thousands of magnificent mansions, which rise aloft like the mountain peaks of the Himalayas. Its streets are filled with elephants, horses, carriages, and foot-passengers, frequented by groups of handsome men and beautiful women, and crowded by men of all sorts and conditions, Brahmans, nobles, artificers, and servants. They resound with cries of welcome to the teachers of every creed, and the city is the resort of the leading men of each of the differing sects. Shops are there for the sale of Benares muslin, of Kotumbara stuffs, and of other cloths of various kinds; and sweet odours are exhaled from the bazaars, where all sorts of flowers and perfumes are tastefully set out. Jewels are there in plenty, such as men's hearts desire, and guilds of traders in all sorts of finery display their goods in the bazaars that face all quarters of the sky. So full is the city of money, and of gold and silver ware, of copper and stone ware, that it is a very mine of dazzling treasures. And there is laid up there much store of property and corn and things of value in warehouses-foods and drinks of every sort, syrups and sweetmeats of every kind. In wealth it rivals Uttara-kuru, and in glory it is as Âlakamandâ, the city of the gods. (The Questions of King Milinda, translated by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890)

References

- Rapson, Edward James (1960). Ancient India: From the Earliest Times to the First Century A. D. Susil Gupta. p. 88.

Sakala, the modern Sialkot in the Lahore Division of the Punjab, was the capital of the Madras who are known in the later Vedic period (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad).

- Kumar, Rakesh (2000). Ancient India and World. Classical Publishing Company. p. 68.

- McEvilley, Thomas (2012). The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781581159332. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- Cohen, Getzel M. (2013-06-02). The Hellenistic Settlements in the East from Armenia and Mesopotamia to Bactria and India. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520953567.

- Kim, Hyun Jin; Vervaet, Frederik Juliaan; Adali, Selim Ferruh (2017-10-05). Eurasian Empires in Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages: Contact and Exchange between the Graeco-Roman World, Inner Asia and China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107190412.

- Congress, Indian History (2007). Proceedings, Indian History Congress.

- Prasad, Prakash Charan (1977). Foreign Trade and Commerce in Ancient India. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9788170170532.

- McEvilley, Thomas (2012). The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781581159332. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- Srivastava, Balram (1968). Trade and commerce in ancient India, from the earliest times to c. A.D. 300. Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office. p. 67.

- Khan, Ahmad Nabi (1977). Iqbal Manzil, Sialkot: An Introduction. Department of Archaeology & Museums, Government of Pakistan. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Wilson, Horace Hayman; Masson, Charles (1841). Ariana Antiqua: A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan. East India Company. p. 197.

sangala rebuilt.

- Society, Panjab University Arabic and Persian (1964). Journal.

- Wilson, Horace Hayman; Masson, Charles (1841). Ariana Antiqua: A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan. East India Company. p. 197.

sangala rebuilt.

- Tarn, William Woodthorpe (2010-06-24). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108009416.