Samuel Lucas

Samuel Lucas (1811–1865) was a British journalist and abolitionist. He was the editor of the Morning Star in London, the only national newspaper in Britain to support the Unionist cause in the American Civil War. He died knowing that legal slavery in America had ended. In 2010 a U.S. Embassy attaché visited the tomb of Samuel Lucas.[1] Lucas lived to hear the "tidings of the destruction of the slave power in the United States"[2]

Samuel Lucas | |

|---|---|

Rev. Cox (left) and Samuel Lucas (right) shown in a detail from The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, by Benjamin Robert Haydon | |

| Born | 1811 |

| Died | 16 April 1865 London |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Abolitionist, editor of the Morning Star |

Biography

Samuel Lucas was born in 1811 to a Quaker family in Wandsworth. Frederick Lucas was his younger brother. His father bought and sold corn. Lucas married his cousin Margaret Bright on 6 September 1839 who was also from a well connected family in the Society of Friends. His wife was to become famous in her own right largely after Lucas's death.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

listwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1841, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG599, Given by British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1880

Lucas worked for many good causes. He attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840 and he was included in the commemorative painting by Benjamin Haydon. Freeing slaves was to be a theme throughout his life. Another interest was secular schools,[3] which Lucas championed in Manchester and where he met Richard Cobden.[4] He had moved there in 1845 as he took an interest in a cotton mill and he stayed there for five years before returning to London. He became active for the Anti-Corn Law League which Cobden and John Bright had founded. His wife Margaret organised meetings and Samuel led them. Meanwhile, his wife took the leading role in caring for their daughter, Katherine, and their mute son.

In August 1847 Lucas was a founding member of the Lancashire-based organisation that was to become the National Public Schools Association. He wrote a Plan for the Establishment of a General System of Secular Education in the County of Lancaster, By 1860 Lucas and his family had moved to London where he became a supporter of the Society for the Repeal of the Taxes on Knowledge.[5]

In March 1856, his brother in law, John Bright in partnership with Cobden created a new newspaper which was called the Morning Star. Lucas was appointed as the paper's editor. Lucas took a strong interest in running the paper where he was the "managing proprietor". Matthew Arnold described the paper as reflecting the "rancour of Protestant dissent in alliance with the vulgarity meddlesomeness and grossness of the British multitude."[6] Eventually Lucas became too ill to regularly attend, and he had to appoint a sub editor. However, he would still oversee the paper, and at times obliged journalists to write a second article that negated an opinion Lucas did not approve of.[7] The paper took a strong line on anti-slavery and the Morning Star was the only national paper to support the Unionist side.[1]

In 1859 Lucas became the editor of the newly established Once A Week, a weekly illustrated literary magazine published by Bradbury and Evans. The magazine was founded after a dispute between Bradbury and Evans and Charles Dickens. The magazine was notable for its illustrations but after Lucas' death it went into decline and ceased printing in 1880.

Lucas died in London on 15 April 1865 of a bronchial illness, and it was noted that he lived long enough to be told of end of the battle of Richmond which marked the end of the American Civil War and slavery in the United States. He was buried in Highgate Cemetery in London, where in time his wife was also buried.[8]

Legacy

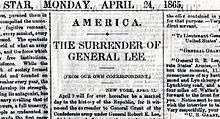

Lucas died before he could see the headlines in the Morning Star that marked the end of slavery. Lucas's paper was the only newspaper that supported the Union side from the start of the war. In 2010 an official from the U.S. Embassy officially paid respect at Lucas's tomb.[1]

Here rest the remains of SAMUEL LUCAS, aged 54. He died on 16 April 1865, a few hours after hearing the tidings of the destruction of the slave power in the United States, by the fall of Richmond; an object which he had unceasingly laboured to promote as Managing-Proprietor of the Morning Star.

Lucas and his wife's tomb in Highgate has been a listed building since 2007.[4]

References

- "Highgate Cemetery salutes a forgotten British hero of the American Civil War". U.S. Embassy in London. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- "Tomb of Samuel Lucas and Margaret Bright Lucas". Commemoration. English Heritage. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- "Obituary - Mr. Samuel Lucas". New York Times. 6 May 1965. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- "Tomb of Samuel Lucas and Margaret Bright Lucas (no 13876) in Highgate (Western) Cemetery". Listed building details. Camden Council. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- Lucas, Samuel (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 34. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Arnold, Matthew; et al. Culture and anarchy. p. 224.

- Cooper, Charles Alfred (1896). An Editor's Retrospect, Fifty Years of Newspaper Work. MacMillan & Co. pp. 98–104.

- "Highgate (Western) Cemetery (tomb no. 13876), Camden, London Listed Grade II in 2007". Retrieved 3 December 2010.

Further reading

- Taylor, Miles; Spencer, H. J. (23 September 2004). "Lucas, Samuel (1811–1865), journalist and educational reformer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17139. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

| Media offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Baxter Langley |

Editor of the Morning Star 1859–1865 |

Succeeded by Justin McCarthy |