Samuel Bogart

Samuel Bogart (2 April 1797 – 11 March 1861) was an itinerant Methodist minister and militia captain from Ray County, Missouri who played a prominent role in the 1838 Missouri Mormon War before later moving to Collin County, Texas, where he became a Texas Ranger and a member of the Texas State Legislature. He is best remembered, however, for his role in leading opposition to Mormon settlers in northwestern Missouri, and for the active role he took in operations against them in the fall of 1838. These operations led to the expulsion of nearly all Mormons from the state following the issuance of Governor Lilburn Boggs' infamous Extermination Order in October of that year.

Samuel Bogart | |

|---|---|

| 2nd Representative of the Texas House of Representatives, Fannin District | |

| In office December 13, 1847 – November 5, 1849 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel McFarland Hiram W. Ryburn |

| Succeeded by | District abolished |

| 3rd Representative of the Texas House of Representatives, District 6 | |

| In office November 5, 1849 – November 3, 1851 | |

| Preceded by | District created |

| Succeeded by | William N. Hardeman |

| 4th Representative of the Texas Senate, District 3 | |

| In office November 3, 1851 – November 7, 1853 | |

| Preceded by | Hardin Hart |

| Succeeded by | Hardin Hart |

| 8th Representative of the Texas House of Representatives, District 6 | |

| In office November 7, 1859 – February 9, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Jacob Baccus |

| Succeeded by | Franklin F. Roberts |

Early years and family

Samuel Bogart was born in Carter County, Tennessee, the son of Cornelius Bogart (1761–1809) and Elizabeth Moffett. Orphaned at the age of fifteen, Bogart enlisted in the U.S. Army during the War of 1812, serving in Capt. Wm. McLeland's company, 7th Infantry. He fought at the Battle of New Orleans, then later in the Black Hawk War in Illinois, where he served as a Major in the Illinois state militia.[1]

Bogart was married to Rachel Hammer on 19 May 1818, in Washington County, Tennessee, and had two sons and three daughters:[2]

- 1) Eliza Ann, born 15 November 1821 in Jacksonville, Morgan County, Illinois; died 17 April 1917 in Caddo County, Oklahoma.

- 2) Cornelius H. Bogart, born 10 March 1823, Morgan County, Illinois; died 3 December 1846 in Illinois.

- 3) William Bogart, born 1826, Schuyler County, Illinois; died August 1828 in Schuyler County, Illinois.

- 4) Jane Elizabeth Bogart, born 17 July 1832, McComb, Schuyler County, Illinois; died 14 April 1918 in Decatur, Wise County, Texas. She married Leroy Clement on 25 July 1846, in Fannin County, Texas. Son Lee Clement married Julia Clement August 24, 1883 in Whitesboro, Texas and had seven children.

- 5) Margaret Ellen Bogart, born 29 Jan 1835, Ray County, Missouri; died 7 May 1906 in Weatherford, Parker County, Texas.

Opposition to the Mormons

Bogart relocated from Illinois to Missouri in 1833, where he settled in rural Ray County in the northwestern part of the state. Here, he served as a farmer and itinerant Methodist minister, as well as the captain of his local militia unit. Peter Burnett, a lawyer from Ray County who would later become the first Governor of California, wrote that Bogart was "not a very discreet man, and his men were pretty much of the same character".[3]

During the fall of 1838, Bogart became involved in an ongoing dispute between members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, commonly known as "Mormons," and their non-Mormon neighbors in Daviess County. Having been forcibly expelled from Jackson County in 1833, the Mormons had migrated north to a county specially created for them by the legislature, Caldwell. However, the influx of new Mormon converts into Missouri caused them to start settling in adjacent counties (including Daviess), which many older settlers felt they had no right to do.[4] Fears arose that the Mormons would take control of all political offices in nearby counties, and this combined with prejudice and fears about the Mormons' economic practices, attitudes toward Native Americans and slaves, and other factors to create an explosive situation by the fall of 1838.[5]

Bogart first took an active role in anti-Mormon activities during a disturbance in Carroll County, where Mormons had established a settlement called De Witt, in violation of an alleged agreement with non-Mormons not to settle in that county. No written agreement to this effect was ever produced, but this did not stop renegade Missouri militiamen from laying siege to the Mormon settlement from October 1 to October 10, 1838. When General Hiram Parks arrived with militia troops—Bogart and his company among them—to restore order, Bogart and his unit immediately sided with the anti-Mormon mob, refusing to obey General Parks' orders to such a point that Parks had to order them back to Ray County to prevent them from joining the vigilantes.[6] Parks unsuccessfully endeavored to have Bogart expelled from the State Guard for his insubordination.[7]

Following a fight between Mormons and non-Mormons during a county election in Gallatin, county seat of Daviess County, Bogart impetuously called out his militia unit, ostensibly to prevent an imminent invasion of Ray County by the Latter Day Saints. No such invasion was actually contemplated, but Bogart decided to act aggressively against the Mormons, anyway.[8] He marched his company to the Caldwell County line, picking up volunteers along the way, then obtained permission from his new superior, General David Atchison, to "range the line" between the two counties to prevent any invasion of Ray County.[9] However, Bogart and his men decided that the defensive posture ordered by Atchison was not to their liking, and so they divided into smaller units and proceeded to disarm Mormons living first in northern Ray County, then in southern Caldwell, as well. Though clearly exceeding his original mandate, Bogart continued to harass and threaten local Mormon settlers and even threatened to give Far West—county seat of Caldwell County, and the main Mormon settlement in Missouri—"thunder and lightning" if the Mormons did not leave the area forthwith.[10] However, Mormon assertions that Bogart plundered Mormon farms and houses have not been substantiated by contemporary witnesses, according to Stephen LeSueur, a modern historian of this conflict.[11] Nevertheless, lurid reports of alleged depredations by Bogart, who was already known for his vehemently anti-Mormon stance, were readily believed by Mormon leaders and historians.

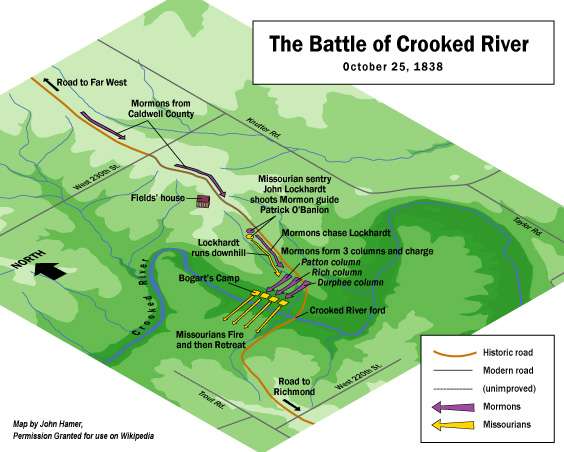

Battle of Crooked River

On the afternoon of 24 October 1838, some of Bogart's men, operating independently of Bogart's main command, took two Mormon spies prisoner at a home where the Mormon "spy company" (a group of Mormons who had been assembled to scout the movements of Bogart and other anti-Mormon vigilantes in the area[12]) was quartered. The two prisoners, after being threatened with death, were taken together with a third prisoner to Bogart's camp on the Crooked River, in northern Ray County, where they were interrogated and further threatened by Bogart's men. Other Mormons living in the house were warned that they would be killed if they had not vacated the county by morning, and they took news of the spies' capture to Joseph Smith and other Mormon leaders in Far West. Although Bogart apparently intended only to hold his prisoners overnight and then release them the next day,[13] the Mormons in Far West believed that he intended to execute them, and accordingly resolved upon a rescue operation.

Led by Mormon apostle David W. Patten, a unit of Mormon militia from Caldwell County crossed into Ray County early in the morning of 25 October, and attacked Bogart's sleeping men at approximately 3 am in their camp alongside the river. A savage fight ensued, resulting in the deaths of three Mormons (including Apostle Patten) and seven wounded, to one dead and six wounded for Bogart's company.[14] The Mormons rescued their hostages and drove Bogart from the field; however, when exaggerated accounts of the battle reached Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs (a notorious anti-Mormon), the governor responded by issuing his infamous "Extermination Order," which directed that the Mormons be "exterminated, or driven from the state"; the State Guard was directed to carry out this order.[15]

Following the Crooked River battle, Bogart (who had survived unscathed) took part in the Missouri militia siege of Far West, which resulted in the final surrender of the Latter Day Saints and their agreement to leave Missouri completely. During the subsequent preliminary hearing before Judge Austin King of Ray County, Bogart and his men were detailed to guard Joseph Smith and other high-ranking Mormon prisoners, as well as those witnesses assembled to testify in their behalf. Bogart and his men intimidated the Mormon leaders and witnesses, even threatening to shoot them on more than one occasion.[16] Following the conclusion of the hearing and the confinement of the Mormon leaders at the jail in Liberty, Missouri, Bogart commenced a search for any Mormons who had participated in the attack on him at Crooked River, intending to shoot any that he might find; he was unsuccessful in this effort, however.[17] Later, after the Mormons and their leaders (who had been permitted to escape from custody) had relocated to Nauvoo, Illinois, Bogart wrote a letter to the postmaster at nearby Quincy, Illinois; he described the Crooked River battle, and named nine alleged participants whom he asked the postmaster's help in locating and apprehending, together with property he claimed the Mormons had stolen from him.[18] No record exists as to whether Bogart ever recovered any of his alleged belongings.

Move to Texas and later years

Following the conclusion of the Mormon War, Bogart was involved in an altercation with fellow-citizen Alexander Beattie during a militia election, during which Bogart shot and killed Beattie, then fled to Texas with a thousand-dollar bounty on his head.[19] He settled in Washington County, where he joined the Texas Rangers and became a company commander in that organization.[20] While in the Rangers, Bogart participated in the abortive Mier Expedition in 1842–43 into Mexico, which resulted in the infamous "black bean" incident, where seventeen Texans were executed after drawing black beans in a random death lottery instituted by orders of Mexican President Santa Anna. Bogart survived his experiences in Mexico, and upon his return to Texas in 1844, settled down in Collin County. Here he would serve four two-year terms in the state legislature, including one as a senator.[21]

Bogart was never brought to justice for his murder of Beattie, nor for any of the depredations he had committed against the Mormons in Missouri.

Bogart resigned from the Texas legislature in 1861 on account of ill health, after signing the Texas ordinance of secession. He died on 11 March 1861, and is buried in Collin County in an unmarked grave.[22]

References

- Major Samuel A. Bogart

- Major Samuel A. Bogart

- Peter H. Burnett, An Old California Pioneer, by Peter H. Burnett, First Governor of the State (Oakland: Biobooks, 1946), p. 34.

- Alexander W. Doniphan, quote.

- The definitive work on the 1838 Mormon War is Stephen C. LeSueur, The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri (University of Missouri Press: 1987). Pertinent information on the origin of the conflict between the Mormons and their Missouri neighbors may be found on pp. 15–27. See also James H. Jenkins, Casus Belli (Blue & Grey Press: 1999), for a brief overview of factors that led to the outbreak of hostilities between the Mormons and the Missourians.

- LeSueur, pp. 101–07. See also Alexander Baugh, Letter of Samuel Bogart to the Quincy Postmaster, pg. 52.

- LeSueur, pg. 132.

- LeSueur, pp. 132–33.

- LeSueur, pg. 133.

- LeSueur, pg. 133.

- LeSueur, pp. 133.

- LeSueur, pg. 131.

- LeSueur, pg. 134, supported by affidavit of Addison Green, one of the two Mormon prisoners.

- LeSueur, pp. 137–43.

- LeSueur, pp. 150–53.

- LeSueur, pg. 198.

- LeSueur, pp. 231–32.

- Alexander Baugh, Letter of Samuel Bogart to the Quincy Postmaster, pg. 54.

- Major Samuel A. Bogart, quoted from American Masonic Register and Literary Companion, vol. 1, pg. 199.

- Major Samuel A. Bogart

- Major Samuel A. Bogart

- Major Samuel A. Bogart