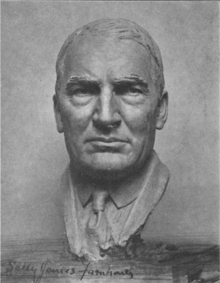

Sally James Farnham

Sally James Farnham was an American sculptor born Ogdensburg, New York, on November 26, 1869, into a prominent local family.

Sally James Farnham | |

|---|---|

Sculptor Sally James Farnham. Photo: Library of Congress | |

| Born | Sarah Welles James November 26, 1869 Ogdensburg, New York |

| Died | April 28, 1943 (aged 73) New York City, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Spouse(s) | |

Early life

.jpg)

Born in Ogdensburg, New York November 26, 1869, Sarah “Sally” Welles James raised in a wealthy household surrounded by military and political figures. Her paternal grandfather, Amaziah Bailey James, served as a Congressman from 1877 to 1881, and her father, Colonel Edward C. James, was a Civil War veteran and a noted trial lawyer in New York City.[1] When James was 10 years old her mother died. Soon after she traveled the world with her father, who often encouraged her to do various activities that were atypical for young women in the period, such as hunting and horsemanship. Her familiarity with these activities later proved useful in her sculpting career.

Education and influences

Her art education began when she was exposed to art as a child while touring the museums of Europe with her family. Their travels would acquaint her with western culture in countries such as France, Norway, and Scotland, as well as with eastern traditions in Japan. At this time she had not discovered her artistic creativity outside of childish drawings and paper-cutout silhouettes. Though she didn't realize it, her exposure to culture made her sensitive toward the artistic sensibilities she would develop in the future. As she later recalled, those days "were loaded with opportunities to study, to absorb unconsciously the great things in line and form of every nation. In fact this was my real schooling. I was heading for sculpture then, though I didn't know it."[1]

In 1896 she married George Paulding Farnham, a designer at Tiffany & Co. with whom she had three children. Throughout her life,she maintained an energetic social life (which included Hollywood friends like Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford) on top of her domestic duties. She began modeling in 1901 while confined to a hospital bed, having been given plasticine clay to amuse herself with. The finished piece, “Spanish Dancer,” was the spark in igniting her passion for sculpture.[2] She later described the experience: “It was as if in some mysterious previous state of existence I had actually been a sculptor and the memory of it was beginning to leak back into my fingers and thumbs.”[1] A family friend, Frederic Remington — who called one of Sally's early works "ugly as sin" yet "full of ginger”[1]—advised her to continue applying herself to the study of sculpture, which she did with the aid of several well-known sculptors, Henry Merwin Shrady, Augustus Lukeman and Frederick Roth.

Her husband was her main supporter and influence at the start of her sculpting education. But Farnham's success as a sculptor would slowly chip away at their marriage. In 1914 she and Paulding were divorced, leaving Sally as the sole provider for her children.

Career in sculpture

The ensuing years saw Farnham produce a series of United States Civil War and cemetery monuments in New York and New Jersey . She received many small grants and commissions that would build her reputation as a sculptor over a very short period of time. In 1904 she won a commission to construct Spirit of Liberty, which she made in honor of her father and the men who gave their lives in the Civil War. By 1907, she was regarded as “one of the leading female sculptors working on a heroic scale in America” [3]

_02.jpg)

In 1910, she was commissioned to create a frieze for the Pan American Union building in Washington D.C. This work, called the Frieze of Discoverers, contributed to her winning a commission from the government of Venezuela to execute the equestrian Simon Bolivar (1921). Originally cast in duplicate, one copy stands at the head of the Avenue of the Americas in New York City. Despite the complications of her divorce two years earlier, in 1916, Sally competed against twenty other sculptors to win this highly prized commission.[3] At the time it was both the largest monument sculpted by a woman and the only equestrian monument of a man created by a female artist. It took five years to complete and earned her the Order of Bolivar (the greatest civilian honor given by the Venezuelan government).

In the following decade Farnham produced a multitude of public monuments and memorials, as well as critically acclaimed portraits of influential individuals including the President of the United States Warren G. Harding, Herbert Hoover, Theodore Roosevelt and Marshal Ferdinand Foch (commander of the Allied Powers in WWI). Her work in portraiture soon became highly sought after and was defined by a highly developed naturalistic style that captured the essence of the subject in a visually masculine and positive manner. Farnham also sculpted busts of notable figures, including violinist Jascha Heifetz and silent film star Mary Pickford, and continued to create sculpture into her seventies.

Her next important monument, Like Hell You Can! (1927) embodied her optimistic spirit in the form of a soldier standing tall, in confrontation with the unknown.

In 1929, she entered into a contract with R.H. Macy and Co. (along with McMein and Fontanne) to create a line of shoes for women.[1]

Of all the monuments she created, Farnham regarded Pay Day (1930) as her best work. The sculpture of four cowboys on horseback, flailing their lassos and kicking up dirt was made in honor of her mentor Frederic Remington, who was a known sculptor of western themes. The energy of the composition contains qualities which she most enjoyed in sculptures and once again displays the optimism with which she led her life. She was particularly drawn to sculptures “that are full of force, feeling and emotional expression.” For her it was important “to believe the whole heart and soul of the artist is in his work. When he can make others believe that, he is a great artist.” [1]

Sally Farnham died in New York City on April 28, 1943. She is buried in the All Saint's Episcopal Church Cemetery in Great Neck, New York. Her tombstone is inscribed, “A merry heart goes all the day,” a reflection of her unyielding optimism.

Major public works

- The Spirit of Liberty (1905), Civil War monument-Library Park, Ogdensburg, New York

- Defenders of the Flag (1908), Civil War monument- Mt. Hope Cemetery, Rochester, New York

- G.A.R. Memorial (1908), Civil War monument-Holy Sepluchure Cemetery, Rochester, New York

- The Frieze of Discoverers (1910)-Pan American Union (now OAS) Building, Washington, D.C.

- Civil War monument (1912)-Bloomfield, New Jersey.

- Simon Bolivar (1921)-Central Park, New York, New York.

- Father Junipero Serra with Indian Boy (1925)-San Fernando Mission, California.

- Like Hell You Can (1926), World War I monument-Fultonville, New York

Private commissioned memorials

- Anna Dick Biardot (1921)-Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York

- Vernon Castle Memorial (1922)-Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York

- Catharine Fonner (1925)-Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York

- Flora at the Preston Pope Satterwhite grave, Cave Hill Cemetery, Louisville, Kentucky

- Wiser-Historic Ogdensburgh Cemetery, Ogdensburg, New York

Medals

- Medal to Commemorate the Erection of the Simon Bolivar Monument in Central Park, 1921

- National Navy Club Medal, 1923

- The John Drew Medal, 1923

Portraits

- Portrait of Theodore Roosevelt, 1906

- Portrait of Jose de Sucre, 1910

- Senator Andrew Wms. Clark, 1915

- Bust of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, c. 1916

- Col. William Hayward, 15th Infantry, 1918

- Bust of Ralph Barton, 1929

References

- Reed, Michael P. (November 2007). "The Intrepid Mrs. Sally James Farnham: An American Sculptor Rediscovered". Aristos.org. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Rubenstein, Charlotte (1986). American Women Artists. Avon Books. pp. 186–193, 201–213. ISBN 0380611015.

- Reed, Michael. "Sally James Farnham". Retrieved 6 March 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sally James Farnham. |

- The Art of Being an Artist: Sally James Farnham, American Sculptor, by Peter H. Hassrick, Frederic Remington Art Museum: Ogdensburg, NY 2005

- http://www.sallyjamesfarnham.org

- Sally James Farnham at Find a Grave