Sacsayhuamán

Saqsaywaman,[1][2] which can be spelled many different ways [3] (possibly from Quechua language, waman falcon[4] or variable hawk)[5], is a citadel on the northern outskirts of the city of Cusco, Peru, the historic capital of the Inca Empire. Sections were first built about 1100 CE by the Killke culture which had occupied the area since 900 CE.

Saqsaywaman | |

A section of the wall of Sacsayhuamán | |

Shown within Peru | |

| Location | Cusco, Cusco Region, Peru |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 13°30′28″S 71°58′56″W |

| Type | Fortification |

| Part of | Cusco |

| History | |

| Cultures | Inca Empire |

The complex was expanded and added to by the Inca from the 13th century; they built dry stone walls constructed of huge stones. The workers carefully cut the boulders to fit them together tightly without mortar. The site is at an altitude of 3,701 m (12,142 ft).

In 1983, Cusco and Sacsayhuamán together were designated as sites on the UNESCO World Heritage List, for international recognition and protection. [6]

Description

Located on a steep hill that overlooks the city, the fortified complex has a wide view of the valley to the southeast. Archeological studies of surface collections of pottery at Sacsayhuamán indicate that the earliest occupation of the hilltop dates to about 900 CE [7].

According to Inca oral history, Tupac Inca

"remembered that his father Pachacuti had called city of Cuzco the lion city. He said that the tail was where the two rivers unite which flow through it, that the body was the great square and the houses round it, and that the head was wanting."

The Inca decided the "best head would be to make a fortress on a high plateau to the north of the city."[8]:105 But archeologists have determined that Sacsayhuamán was originally built by the preceding Killke culture. Beginning about the 13th century, the Inca expanded on this monumental construction.

After the Battle of Cajamarca during the Spanish Conquest of the Inca, Francisco Pizarro sent Martin Bueno and two other Spaniards to transport the gold and silver from the Temple of Coricancha in Cusco to Cajamarca, where the Spaniards were based. [9]:228–230 They found the Temple of the Sun "covered with plates of gold", which the Spanish ordered removed as payment for Atahualpa's ransom. Seven hundred plates were removed, and added to two hundred cargas of gold transported back to Cajamarca. The royal mummies, draped in robes, and seated in gold embossed chairs, were left alone. But, while desecrating the temple, Pizarro's three men also defiled the Virgins of the Sun, sequestered women who were considered sacred and served at the temple.[10]:192–193

After Francisco Pizarro finally entered Cuzco, his brother Pedro Pizarro described what they found,

"on top of a hill they [the Inca] had a very strong fort surrounded with masonry walls of stones and having two very high round towers. And in the lower part of this wall there were stones so large and thick that it seemed impossible that human hands could have set them in place...they were so close together, and so well fitted, that the point of a pin could not have been inserted in one of the joints. The whole fortress was built up in terraces and flat spaces." The numerous rooms were "filled with arms, lances, arrows, darts, clubs, bucklers and large oblong shields...there were many morions...there were also...certain stretchers in which the Lords travelled, as in litters."[11]:45 Pedro Pizarro described in detail storage rooms that were within the complex and filled with military equipment.[12]

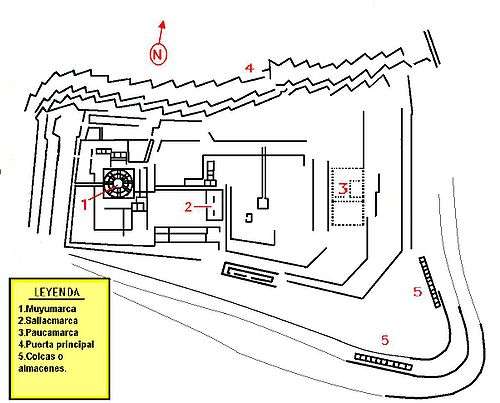

Because of its location high above Cusco and its immense terrace walls, Sacsayhuamán is frequently referred to as a fortress.[13] The importance of its military functions was highlighted in 1536 when Manco Inca lay siege to Cusco.[14] Much of the fighting occurred in and around Sacsayhuamán, as it was critical to maintaining control over the city. Descriptions of the siege, as well as excavations at the site, have documented original towers on the summit of the site, and a series of other buildings. For example, Pedro Sancho, who visited the complex before the siege, said that the complex was like a labyrinth, and had numerous storage rooms filled with a wide variety of items. He also noted that there were buildings with large windows that looked over the city. These structures, like so much of the site, have long since been destroyed.[15][13]

The large plaza, capable of holding thousands of people, was designed for communal ceremonial activities. Several of the large structures at the site may also have been used during rituals. A similar relationship to that between Cuzco and Sacsayhuamán was replicated by the Inca in their distant colony where Santiago, Chile developed. The Inca fortress there, known as Chena, predated the Spanish colonial city. It was a ceremonial ritual site known as Huaca de Chena.[16]

The best-known zone of Sacsayhuamán includes its great plaza and its adjacent three massive terrace walls. The stones used in the construction of these terraces are among the largest used in any building in pre-Hispanic America. They display a precision of cutting and fitting that is unmatched in the Americas.[13] The stones are so closely spaced that a single piece of paper will not fit between many of the stones. This precision, combined with the rounded corners of the blocks, the variety of their interlocking shapes, and the way the walls lean inward, is thought to have helped the ruins survive devastating earthquakes in Cuzco. The longest of the three walls is about 400 meters. They are about 6 meters tall. The estimated volume of stone is over 6,000 cubic meters. Estimates for the weight of the largest andesite block vary from 128 tonnes to almost 200 tonnes.[17][18]

Following the siege of Cusco, the Spaniards began to use Sacsayhuamán as a source of stones for building Spanish Cuzco; within a few years, they had taken apart and demolished much of the complex. The site was destroyed block by block to salvage materials with which to build the new Spanish governmental and religious buildings of the colonial city, as well as the houses of the wealthiest Spaniards. In the words of Garcilaso de la Vega (1966:471 [1609: Part 1, Book. Bk. 7, Ch. 29]):

"to save themselves the expense, effort and delay with which the Indians worked the stone, they pulled down all the smooth masonry in the walls. There is indeed not a house in the city that has not been made of this stone, or at least the houses built by the Spaniards."

Today, only the stones that were too large to be easily moved remain at the site.[13]

On 13 March 2008, archaeologists discovered additional ruins at the periphery of Sacsayhuamán. They are believed to have been built by the Killke culture, which preceded the Inca. While appearing to be ceremonial in nature, the exact function remains unknown. This culture built structures and occupied the site for hundreds of years before the Inca, between 900 and 1200 CE.[19]

In January 2010, parts of the site were damaged during periods of heavy rainfall in the region.[20]

Theories about construction

The Inca used similar construction techniques in building Sacsayhuamán as they used on all their stonework, albeit on a far more massive scale.[13] The stones were rough-cut to the approximate shape in the quarries using river cobbles.[21] They were dragged by rope to the construction site, a feat that at times required hundreds of men.[22] The ropes were so impressive that they warranted mention by Diego de Trujillo (1948:63 [1571]) as he inspected a room filled with building materials. The stones were shaped into their final form at the building site and then laid in place.[23] The work, while supervised by Inca architects, was largely carried out by groups of individuals fulfilling their labor obligations to the state. In this system of mita or "turn" labor, each village or ethnic group provided a certain number of individuals to participate in such public works projects.[13]

Although multiple regions might provide labor for a single, large-scale state project, typically each work-gang was of the same ethnicity. Different groups were assigned different tasks. Pedro Cieza de León, who twice visited Sacsayhuamán in the late 1540s, mentions the quarrying and moving of the stones to the site, and the construction of foundation trenches. All this was conducted by rotational labor under the close supervision of Imperial architects.[13]

Jean-Pierre Protzen, a professor of architecture, has shown how the Inca built long and complex ramps within the stone quarries near Ollantaytambo, and how additional ramps were built to drag the blocks to the construction above the village.[24] He suggests that similar ramps would have been built at Sacsayhuamán.

Modern-day use

Peruvians continue to celebrate Inti Raymi, the annual Inca festival of the winter solstice and new year.[25] It is held near Sacsayhuamán on 24 June. Another important festival is Warachikuy, held there annually on the third Sunday of September.[26]

Some people from Cusco use the large field within the walls of the complex for jogging, t'ai chi, and other athletic activities.

See also

- List of buildings and structures in Cusco

- List of megalithic sites

- Huaca de Chena

References

- Cusco Info - Saqsaywaman

- Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua, Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco, Cusco 2005

- Diego Gonçález Holguín. Vocabulario de la Lengva General de todo el Perv llamada Lengva Qquichua o del Inca. Lima, imprenta de Francisco del Canto, 1608. p. 26f.: La fortaleza del Inca en el Cuzco era Çaçça huaman y Çaççay huaman significa "Águila real la mayor" y no halcón satisfecho como se ha interpretado generalmente. p. 75: Çacça huaman pucara. Vn castillo del Inga en el Cuzco. Çacçay huaman, o anca. Aguila real la mayor.

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary): waman - s. Halcón. Ave rapaz diurna.

- Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua, Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco, Cusco 2005: waman. - s. Zool. (Buteo poecilochros Gurney) Aguilucho cordillerano. Orden falconiformes. Familia accipitridae. Ave de color gris– plomo, con áreas ferruginosas, blancas, negras y cafés. SINÓN: wamancha.

- "City of Cuzco - World Heritage Site". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- [{https://www.worldbyisa.com/20-things-to-do-in-cusco/ WorldByIsa: Things to do in Cusco]]

- de Gamboa, P.S., (2015), History of the Incas, Lexington, ISBN 9781463688653

- Leon, P., 1998, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, Chronicles of the New World Encounter, edited and translated by Cook and Cook, Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822321460

- Prescott, W.H., 2011, The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142

- Pizzaro, P., 1571, Relation of the Discovery and Conquest of the Kingdoms of Peru, Vol. 1–2, New York: Cortes Society, RareBooksClub.com, ISBN 9781235937859

- Pizarro 1921:272–273

- Brian S. Bauer (28 June 2010). Ancient Cuzco: Heartland of the Inca. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-79202-9. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- Hemming 1970; Conquest of the Incas

- Hyslop 1990

- Stehberg Ruben, "La Fortaleza de Chena y su relación con la ocupación incaica de Chile central." Occasional publication N ° 23, História Natural's National Museum, Santiago, Chile, 1976.

- Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World, ed. Chris Scarre, 1999 pp. 220–23

- Readers Digest: "Mysteries of the Ancient Americas: The New World Before Columbus", 1986, pp. 220–21

- "Pre-Inca temple uncovered in Peru", CNN, 15 Mar 2008, Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "Heavy rainfall in Peru", BBC News, 26 January 2010

- (Protzen 1986; 1991)

- (Gutierrez de Santa Clara 1963:252 [ca. 1600])

- (Lee 1986)

- Protzen, Jean-Pierre; Batson, Robert (1991). Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo. Oxford University Press. pp. 165, 175. ISBN 978-0-19-507069-9.

- "Stonehenge y Cuzco, dos destinos unidos por el culto al sol". La Vanguardia. 20 June 2017.

- mincetur.gob.pe "Fiesta del Warachikuy" (in Spanish), accessed 26 February 2014