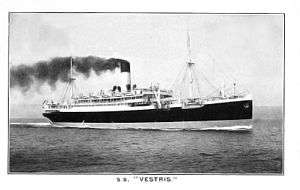

SS Vestris

SS Vestris was a 1912 steam ocean liner operated by Lamport and Holt Line and used on its service between New York and the River Plate. On 12 November 1928 she began listing about 200 miles off Hampton Roads, Virginia, was abandoned, and sank, killing more than 100 people. Her wreck is thought to lie some 1.2 miles (2 km) beneath the North Atlantic.[2]

Postcard of Vestris | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Vestris |

| Owner: | Liverpool, Brazil and River Plate Steam Navigation Co |

| Operator: | Lamport and Holt |

| Builder: | Workman, Clark & Co, Belfast |

| Yard number: | 303 |

| Launched: | 16 May 1912 |

| Maiden voyage: | 19 September 1912 from Liverpool to the River Plate. 26 October 1912 First sailing to New York |

| Identification: | official number 131451 |

| Fate: | Sank 12 November 1928 |

| Notes: | Final voyage from Hoboken, New Jersey sailing from New York to Barbados and South American ports 10 November 1928 – 12 November 1928 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | |

| Length: | 496 feet (151 m) between posts, 511 feet (156 m) overall |

| Beam: | 60 feet 6 inches (18.44 m) |

| Draught: | Salt water draught in 1912 by Lloyds, 26 feet 9¼ inches for summer, and 26 feet 3¼ inches for winter. Salt water draught on her final voyage was found to have been 26 feet 11½ inches[1] |

| Installed power: | 614 NHP, producing 8,000 IHP |

| Propulsion: | 2 × 4-cylinder quadruple-expansion engines, twin screw |

| Speed: | 15 knots (28 km/h) |

| Capacity: | Passengers: 280 First Class, 130 Second Class, 200 Third Class. 5 cargo holds. |

| Crew: | 250 |

| Notes: | sister ships: Vandyck, Vauban |

The sinking attracted much press coverage at the time and remains notable for the loss of life, particularly of women and children when the ship was being abandoned.[3][4][5] The sinking and subsequent inquiries may also have shaped the second International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in 1929.[6]

Building

In 1911–13 Workman, Clark & Company of Belfast, Ireland built three sister ships for Lamport and Holt. Vandyck was launched in 1911, Vauban in January 1912 and Vestris in May 1912. The trio were similar in size to Vasari that Sir Raylton Dixon & Co built for Lamport and Holt in 1909. Vauban and Vestris had passenger accommodation slightly larger than that of their older sister Vandyck.[7] Since 1906 Lamport and Holt policy was to name its passenger liners after artists and engineers beginning with "V". Together they became known as "V-class ships".[8]

Vestris was built as yard number 303[9] and launched 16 May 1912[10] and made her maiden voyage on 19 September 1912 from Liverpool to River Plate.[11] She had five double-ended boilers to supply steam to a pair of quadruple-expansion engines. These drove twin screws and gave her a speed of 15 knots (28 km/h).[8]

Service history

Vandyck, Vauban and Vestris were intended for Lamport and Holt's service between Liverpool and Buenos Aires via Vigo, Leixões and Lisbon. But in 1911 the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company had taken over Lamport and Holt. RMSP chartered Vauban for a new and quicker service between Southampton and the River Plate, leaving Lamport and Holt unable to compete. RMSP returned Vauban to Lamport and Holt by the end of 1913, but effectively forced L&H out of the route between Britain and the River Plate.[8]

Lamport and Holt then transferred Vandyck, Vauban and Vestris to strengthen its service between New York and the River Plate via Trinidad and Barbados, where they became the largest and most luxurious ships on the route.[7] But soon after World War I began the German cruiser SMS Karlsruhe captured and sank Vandyck on 26 October 1914.[12]

Vestris was chartered as a troopship to cross the Atlantic Ocean from the USA to France. On 26 January 1918 a torpedo narrowly missed her in the English Channel.[13][14][15]

Soon after WW1, Vasari, Vauban and Vestris began a triangular passenger service, sailing anti-clockwise from New York to the River Plate, from there to Liverpool and then by charter to Cunard Line from Liverpool to New York. In 1919 Vestris completed this circuit six times.[11] By 1923 the three ships offered regular fortnightly sailings on the triangular route.[8]

In September 1919, Vestris, carrying 550 people, suffered damage from a fire in her coal bunkers. The crew fought the fire for four days before either HMS Dartmouth[11][16] or HMS Yarmouth[17] escorted the ship to Saint Lucia in the West Indies. Several days later the fire was extinguished.[17][18]

In 1922 the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company briefly chartered Vestris.[11]

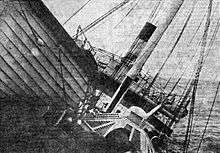

Sinking

Vestris left New York bound for the River Plate on 10 November 1928 with 325 passengers and crew. On 11 November she ran into a severe storm that flooded her boat deck and swept away two of her lifeboats. Part of her cargo and bunker coal shifted, causing the ship to list to starboard.[19] Through numerous leaks[14] she took on water faster than her pumps could remove it.[19]

On 12 November the ship's list worsened. At 9:56 a.m. she sent an SOS message giving her position as latitude 37° 35' N. and longitude 71° 81' [sic] W., which was incorrect by about 37 miles. The SOS was repeated at 11:04 a.m..[1]

Between 11 a.m. and noon, while the ship was off Norfolk, Virginia, the order was given to man lifeboats and the ship was abandoned. Two hours later, at about 2 p.m., Vestris sank at lat. 37° 38' N, long. 70° 23' W.[1] The rescue vessels arriving on the scene, late in the evening of 12 November and early in the morning of 13 November, were the steamships American Shipper, Myriam, and Berlin and battleship USS Wyoming.[1][20]

Death toll

Estimates of the dead vary from 110 to 127. Time and The New York Times reported that from the complement of 128 passengers and 198 crew on board, 111 people were killed:[3][21]

- 68 dead or missing from a total 128 passengers. 60 passengers survived.

- 43 dead or missing from a total of 198 crew members. 155 crew survived.

None of the 13 children and only eight of the 33 women aboard the ship survived. The captain of Vestris, William J Carey, went down with his ship. 22 bodies were recovered by rescue ships.

The father of future Major League Baseball pitcher Sam Nahem was among those who drowned when the ship sank.[22]

Aftermath

Press reports after the sinking were critical of the crew and management of Vestris. In the wake of the disaster, Lamport and Holt experienced a dramatic drop in bookings for the company's other liners and their service to South America ceased at the end of 1929.

Many inquiries and investigations were held into the sinking of Vestris.[3] Criticism was made of:

- Overloading of the vessel.

- The conduct of the Master, officers and crew of the vessel.

- Delays in issuing an SOS call.

- Poor decisions made during deployment of the lifeboats, which led to the two of the first three lifeboats to be launched (containing mostly women and children) sinking with Vestris and another being swamped.

- Legal requirements governing lifeboats and out-dated life-preservers.

- Lack of radio sets in nearby vessels at the time.

Lawsuits were brought after the sinking on behalf of 600 claimants totaling $5,000,000.[4]

Vestris' sinking was covered by Associated Press reporter Lorena Hickok. Her story on the event became the first to appear in The New York Times under a woman's byline.[23]

References

- United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (24 May 1932). "Vestris – Decision on the Merits". Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Warwick, Sam; Roussell, Mike (2012). Shipwrecks of the Cunard Line. p. 145.

- "Catastrophe: Vestris". Time. 26 November 1928.

- "Vestris Disaster Company's Liability U.S Courts Ruling". Wellington Evening Post. National Library of New Zealand. 18 September 1931. p. 7.

- "Vestris Inquiry – Further evidence wireless messages unsolved mystery". Wellington Evening Post. CVI (116). National Library of New Zealand. 20 November 1928. p. 11.

- "Damaging evidence ship and boats leaking disobedience of crew". Wellington Evening Post. CVI (116). National Library of New Zealand. 22 November 1928. p. 11.

- "Vestris Inquiry. Officers' evidence cargo breaks bulkhead". The Canberra Times. National Library of Australia. 19 November 1928. p. 1.

- McDowell, Carl E; Gibbs, Helen M (1999) [1954]. "21: International Conventions and Treaties". Ocean Transportation. Washington, DC: Beardbooks. p. 431. ISBN 9781893122451.

- Heaton 2004, p. 48.

- Dunn 1973, p. 111.

- Allen, Tony; Dr Juice. "SS Vestris (+1914)". Wrecksite. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Launches-Irish". The Marine Engineer and Naval Architect. XXXIV: 455. 1912. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "Lamport & Holts' S.S. "Vestris"". Blue Star on the Web. 3 February 2012.

- Heaton 2004, p. 59.

- Heaton 2004, p. 61.

- "The Vestris Disaster". Blue Star on the Web. 3 February 2012.

- Donahue, James. "Faulty Coal Port Blamed In Vestris Disaster". Ships.

- Heaton, Paul M (1977). "The Lamport and Holt Fleet, Part III: 1918–1940". Sea Breezes.

- "Liner afire 4 days with 550 aboard". The New York Times. 16 September 1919.

- "Fire on Liner put out". The New York Times. 23 September 1919.

- Heaton 2004, p. 71.

- Kalafus, Jim (18 December 2006). "My God the Boat Is leaving Us". Encyclopedia Titanica.

- "Death Toll is now 111". The New York Times. 16 November 1928. p. 1.

- TheDeadballEra.com: "Sam Nahem's Obit"

- Martinelli, Diana Knott; Bowen, Shannon A (2009). "The Public Relations Work of Journalism Trailblazer and First Lady Confidante Lorena Hickok, 1937–45". Journalism History. 35 (3): 131–40. doi:10.1080/00947679.2009.12062795.

Sources and further reading

- Dunn, Laurence (1973). Merchant Ships of the World in Colour 1910–1929. London: Blandford Press Ltd. pp. 110–111. ISBN 0-7137-0569-8.

- Heaton, Paul M (1986). Lamport & Holt. Newport: Starling Press. ISBN 0-950771-46-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heaton, Paul M (2004). Lamport & Holt Line. Abergavenny: PM Heaton Publishing. ISBN 1-872006-16-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "SOS! – A challenge to science". Popular Science Monthly: 30–31. February 1929.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Disaster at Sea: SS Vestris". Cruising the Past.

- "Passenger Ship Disasters – Part 5". Ships Nostalgia. Jelsoft Enterprises. 2006.