Occupation of the Ruhr

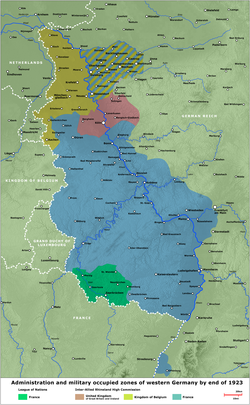

The Occupation of the Ruhr (German: Ruhrbesetzung) was a period of military occupation of the Ruhr region of Germany by France and Belgium between 11 January 1923 and 25 August 1925.

| Occupation of the Ruhr | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Aftermath of World War I and Political violence in Germany (1918–33) | |||||||

French soldiers and a German civilian in the Ruhr in 1923. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

German protesters | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 130 civilians killed | |||||||

France and Belgium occupied the heavily industrialized Ruhr Valley in response to Germany defaulting on reparation payments dictated by the victorious powers after World War I in the Treaty of Versailles. Occupation of the Ruhr worsened the economic crisis in Germany,[1] and German civilians engaged in acts of passive resistance and civil disobedience, during which 130 were killed. France and Belgium, facing economic and international pressure, accepted the Dawes Plan to restructure Germany's payment of war reparations in 1924 and withdrew their troops from the Ruhr by August 1925.

The Occupation of the Ruhr contributed to German re-armament and the growth of radical right-wing movements in Germany.[1]

Background

The Ruhr region had been occupied by Allied troops in the aftermath of the First World War. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles (1919), which formally ended the war with the Allies as the victors, Germany was forced to accept responsibility for the damages caused in the war and was obliged to pay war reparations to the various Allies. Since the war was fought predominately on French soil, these reparations were paid primarily to France. The total sum of reparations demanded from Germany—around 226 billion gold marks (US $917 billion in 2020)—was decided by an Inter-Allied Reparations Commission. In 1921, the amount was reduced to 132 billion (at that time, $31.4 billion (US $442 billion in 2020), or £6.6 billion (UK£284 billion in 2020)).[2] Even with the reduction, the debt was huge. As some of the payments were in raw materials, which were exported, German factories were unable to function, and the German economy suffered, further damaging the country's ability to pay.[3]

By late 1922, the German defaults on payments had grown so regular that a crisis engulfed the Reparations Commission; the French and Belgian delegates urged occupying the Ruhr as a way of forcing Germany to pay more, while the British delegate urged a lowering of the payments.[4] As a consequence of a German default on timber deliveries in December 1922, the Reparations Commission declared Germany in default, which led to the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr in January 1923.[5] Particularly galling to the French was that the timber quota the Germans defaulted on was based on an assessment of their capacity the Germans made themselves and subsequently lowered.[6] The Allies believed that the government of Chancellor Wilhelm Cuno had defaulted on the timber deliveries deliberately as a way of testing the will of the Allies to enforce the treaty.[6] The entire conflict was further exacerbated by a German default on coal deliveries in early January 1923, which was the thirty-fourth coal default in the previous thirty-six months.[7][8] Frustrated at Germany not paying reparations, Raymond Poincaré, the French Prime Minister, hoped for joint Anglo-French economic sanctions against Germany in 1922 and opposed military action. However, by December 1922 he saw coal for French steel production and payments in money as laid out in the Treaty of Versailles draining away.

Occupation

After much deliberation, Poincaré decided to occupy the Ruhr on 11 January 1923 to extract the reparations himself. The real issue during the Ruhrkampf (Ruhr campaign), as the Germans labelled the battle against the French occupation, was not the German defaults on coal and timber deliveries but the sanctity of the Versailles Treaty.[9] Poincaré often argued to the British that letting the Germans defy Versailles in regards to the reparations would create a precedent that would lead to the Germans dismantling the rest of the Versailles treaty.[10] Finally, Poincaré argued that once the chains that had bound Germany in Versailles were destroyed, it was inevitable that Germany would plunge the world into another world war.

Initiated by Poincaré, the invasion took place on 11 January 1923. General Alphonse Caron's 32nd infantry corps, under the supervision of General Jean-Marie Degoutte, carried out the operation.[11] Some theories state that the French aimed to occupy the centre of German coal, iron, and steel production in the Ruhr area valley simply to get the money. Some others state that France did it to ensure that the reparations were paid in goods, because the mark was practically worthless due to hyperinflation that already existed at the end of 1922. Since the territory of the Saar Basin was separated from Germany, the supply of iron ore fell on the French side and coal on the German side, but the two commodities had far more value together than separately: the supply chain had grown tightly integrated during the industrialization of Germany after 1870, but the problems of currency, transportation and import/export barriers threatened to destroy the steel industry in both countries.[12] Eventually, this problem was resolved in the post-World War II European Coal and Steel community.[13]

Following France's decision to invade the Ruhr,[14] the Inter-Allied Mission for Control of Factories and Mines (MICUM)[15] was set up as a means of ensuring coal repayments from Germany.[16]

Civil Disobedience and Passive Resistance from the German People

The Allied occupation was greeted by a campaign of both passive resistance and civil disobedience from the German inhabitants. Approximately 130 German civilians were killed by the French occupation army during the events, including during civil disobedience protests, e.g., against dismissal of German officials.[17][18] Some theories assert that to pay for passive resistance in the Ruhr, the German government began the hyperinflation that destroyed the German economy in 1923.[9] Others state that the road to hyperinflation was well established before with the reparation payments that started on November 1921,[19] see 1920s German inflation. In the face of economic collapse, with high unemployment and hyperinflation, the strikes were eventually called off in September 1923 by the new Gustav Stresemann coalition government, which was followed by a state of emergency. Despite this, civil unrest grew into riots and coup attempts targeted at the government of the Weimar Republic, including the Beer Hall Putsch. The Rhenish Republic was proclaimed at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) in October 1923.[20]

Though the French succeeded in making their occupation of the Ruhr pay, the Germans, through their passive resistance in the Ruhr and the hyperinflation that wrecked their economy, won the world's sympathy, and under heavy Anglo-American financial pressure (the simultaneous decline in the value of the franc made the French very open to pressure from Wall Street and the City), the French were forced to agree to the Dawes Plan of April 1924, which substantially lowered German reparations payments.[21] Under the Dawes Plan, Germany paid only 1 billion marks in 1924, and then increasing amounts for the next three years, until the total rose to 2.25 billion marks by 1927.

Sympathy for Germany

Internationally, the French invasion of Germany did much to boost sympathy for the German Republic, although no action was taken in the League of Nations since it was technically legal under the Treaty of Versailles.[22] The French, with their own economic problems, eventually accepted the Dawes Plan and withdrew from the occupied areas in July and August 1925. The last French troops evacuated Düsseldorf and Duisburg along with the city's important harbour in Duisburg-Ruhrort, ending French occupation of the Ruhr region on 25 August 1925. According to Sally Marks, the occupation of the Ruhr "was profitable and caused neither the German hyperinflation, which began in 1922 and ballooned because of German responses to the Ruhr occupation, nor the franc's 1924 collapse, which arose from French financial practices and the evaporation of reparations".[23] Marks suggests the profits, after Ruhr-Rhineland occupation costs, were nearly 900 million gold marks.[24]

British perspective

When on 12 July 1922, Germany demanded a moratorium on reparation payments, tension developed between the French government of Poincaré and the coalition government of David Lloyd George. The British Labour Party demanded peace and denounced Lloyd George as a troublemaker. It saw Germany as the martyr of the postwar period and France as vengeful and the principal threat to peace in Europe. The tension between France and Britain peaked during a conference in Paris in early 1923, by which time the coalition led by Lloyd George had been replaced by the Conservatives. The Labour Party opposed the occupation of the Ruhr throughout 1923, which it rejected as French imperialism. The British Labour Party believed it had won when Poincaré accepted the Dawes Plan in 1924.[25]

French perspective

Despite his disagreements with Britain, Poincaré desired to preserve the Anglo-French entente and thus moderated his aims to a degree. His major goal was the winning of the extraction of reparations payments from Germany. His inflexible methods and authoritarian personality led to the failure of his diplomacy.[26]

Aftermath

Dawes Plan

To deal with the implementation of the Dawes Plan, a conference took place in London in July–August 1924.[27] The British Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, who viewed reparations as impossible to pay, successfully pressured the French Premier Édouard Herriot into a whole series of concessions to Germany.[27] The British diplomat Sir Eric Phipps commented that "The London Conference was for the French 'man in the street' one long Calvary as he saw M. Herriot abandoning one by one the cherished possessions of French preponderance on the Reparations Commission, the right of sanctions in the event of German default, the economic occupation of the Ruhr, the French-Belgian railroad Régie, and finally, the military occupation of the Ruhr within a year".[28] The Dawes Plan was significant in European history as it marked the first time that Germany had succeeded in defying Versailles, and revised an aspect of the treaty in its favour.

The Saar region remained under French control until 1935.

German politics

In German politics, the French occupation of the Rhineland accelerated the formation of right-wing parties. Disoriented by the defeat in the war, conservatives in 1922 founded a consortium of nationalist associations, the "Vereinigten Vaterländischen Verbände Deutschlands" (VVVD, United Patriotic Associations of Germany). The goal was to forge a united front of the right. In the climate of national resistance against the French Ruhr invasion, the VVVD reached its peak strength. It advocated policies of uncompromising monarchism, corporatism and opposition to the Versailles settlement. However, it lacked internal unity and money and so never managed to unite the right. It had faded away by the late 1920s, as the NSDAP (Nazi party) emerged.[29]

See also

References

- "Hyperinflation and the invasion of the Ruhr – The Holocaust Explained: Designed for schools". The Holocaust Explained. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Timothy W. Guinnane (January 2004). "Vergangenheitsbewältigung: the 1953 London Debt Agreement" (PDF). Center Discussion Paper no. 880. Economic Growth Center, Yale University. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- The extent to which payment defaults were genuine or artificial is controversial, see World War I reparations.

- Marks, pp. 239–240.

- Marks, pp. 240–241.

- Marks, p. 240.

- Marks, p. 241.

- Marks, p. 244.

- Marks, p. 245.

- Marks, pp. 244–245.

- Mordacq, Henri. Die deutsche Mentalitat. Funf Jahre B. am Rhein. p. 165.

- John Maynard Keynes, The economic consequences of the Peace.

- "Declaration of 9 may - Robert Schuman Foundation". www.robert-schuman.eu. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- Fischer, p. 28.

- Fischer, p. 42.

- Fischer, p. 51.

- "Anaconda Standard". 1923-02-10.

Twenty Germans were said to have been killed and several French soldiers wounded when a mob at Rapoch attempted to prevent the expulsion of one hundred officials. Picture shows French guard being doubled outside the station at Bochum following a collision between German mob and the French

- "Hanover Evening Sun". 1923-03-15.

Three Germans killed in Ruhr by French sentries

- Ferguson, Adam; When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany p. 38. ISBN 1-58648-994-1

- "WHKMLA : The French Occupation of the Rhineland, 1918-1930". www.zum.de. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- Marks, pp. 245–246.

- Walsh, p. 142.

- Sally Marks, '1918 and After. The Postwar Era', in Gordon Martel (ed.), The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered. Second Edition (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 26.

- Marks, p. 35, no. 57.

- Aude Dupré de Boulois, "Les Travaillistes, la France et la Question Allemande (1922–1924)," Revue d'Histoire Diplomatique (1999) 113 No. 1 pp. 75–100.

- Hines H. Hall, III, "Poincare and Interwar Foreign Policy: 'L'Oublie de la Diplomatie' in Anglo-French Relations, 1922–1924," Proceedings of the Western Society for French History (1982), Vol. 10, pp. 485–494.

- Marks, p. 248.

- Marks, p. 249.

- James M. Diehl, "Von Der 'Vaterlandspartei' zur 'Nationalen Revolution': Die 'Vereinigten Vaterländischen Verbände Deutschlands (VVVD)' 1922–1932," [From "party for the fatherland" to "national revolution": the United Fatherland Associations of Germany (VVVD), 1922–32] Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (October 1985) 33 No. 4 pp. 617–639.

Sources

- Fischer, Conan. The Ruhr Crisis, 1923–1924 (Oxford U.P., 2003); online review

- Marks, Sally. "The Myths of Reparations," Central European History, Volume 11, Issue No. 3, September 1978 pp. 231–255.

- O'Riordan, Elspeth Y. "British Policy and the Ruhr Crisis 1922–24," Diplomacy & Statecraft (2004) 15 No. 2 pp. 221–251.

- O'Riordan, Elspeth Y. Britain and the Ruhr Crisis (London, 2001);

- Walsh, Ben. History in Focus: GCSE Modern World History;

French and German

- Stanislas Jeannesson, Poincaré, la France et la Ruhr 1922–1924. Histoire d'une occupation (Strasbourg, 1998);

- Michael Ruck, Die Freien Gewerkschaften im Ruhrkampf 1923 (Frankfurt am Main, 1886);

- Barbara Müller, Passiver Widerstand im Ruhrkampf. Eine Fallstudie zur gewaltlosen zwischenstaatlichen Konfliktaustragung und ihren Erfolgsbedingungen (Münster, 1995);

- Gerd Krüger, Das "Unternehmen Wesel" im Ruhrkampf von 1923. Rekonstruktion eines misslungenen Anschlags auf den Frieden, in Horst Schroeder, Gerd Krüger, Realschule und Ruhrkampf. Beiträge zur Stadtgeschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts (Wesel, 2002), pp. 90–150 (Studien und Quellen zur Geschichte von Wesel, 24) [esp. on the background of so-called 'active' resistance];

- Gerd Krumeich, Joachim Schröder (eds.), Der Schatten des Weltkriegs: Die Ruhrbesetzung 1923 (Essen, 2004) (Düsseldorfer Schriften zur Neueren Landesgeschichte und zur Geschichte Nordrhein-Westfalens, 69);

- Gerd Krüger, "Aktiver" und passiver Widerstand im Ruhrkampf 1923, in Günther Kronenbitter, Markus Pöhlmann, Dierk Walter (eds.), Besatzung. Funktion und Gestalt militärischer Fremdherrschaft von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert (Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich, 2006), pp. 119–30 (Krieg in der Geschichte, 28);

External links

- Occupation after the War (France and Belgium) at 1914-1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Ruhr Occupation at 1914-1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War.