Rudrasimha I

Rudrasimha I was a Western Kshatrapa ruler, who reigned from 178 to 197 CE. He was son of Rudradaman I, grandson of Jayadaman, and grand-grandson of Chashtana.[2]

Obv: Bust of Rudrasimha, with corrupted Greek legend "..OHIIOIH.." (Indo-Greek style).

Rev: Three-arched hill or Chaitya, with river, crescent and sun, within Prakrit legend in Brahmi script:Rajno Mahaksatrapasa Rudradamnaputrasa Rajna Mahaksatrapasa Rudrasihasa "King and Great Satrap Rudrasimha, son of King and Great Satrap Rudradaman".

From the reigns of Jivadaman and Rudrasimha I, the date of minting of each coin, reckoned in the Saka era, is usually written on the obverse behind the king's head in Brahmi numerals, allowing for a quite precise datation of the rule of each king.[3][4] This is a rather uncommon case in Indian numismatics. Some, such as the numismat R.C Senior considered that these dates might correspond to the much earlier Azes era instead.

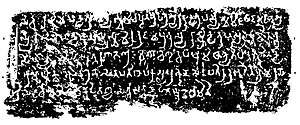

Rudrasimha I is also known for an inscription in Sanskrit at Gunda, north Kathiawar, mentioning "the digging of a well for the welfare of society by Senapati Bapaka's son, Rudrabhuti Abhira", and dated to Saka era 103 (181 CE).[5][6][7][2] The inscription also gives a detailed genealogy of the kings up to Rudrasimha:[8]

"Hail ! On the [auspicious] fifth tithi of the bright fortnight of Vaisakha during the auspicious period of the constellation of Rohini, in the year one hundred and three — 100 3 — (during the reign) of the king, the Kshatrapa Lord Rudrasiha (Rudrasimha), the son of the king, the Maha-Kshatrapa Lord Rudradaman (and) son’s son of the king, the Kshatrapa Lord Jayadaman, (and) grandson’s son of the king, the Maha-Kshatrapa Lord Chashtana, the well was caused to be dug and embanked by the general (senapati) Rudrabuthi, the son of the general (senapati) Bapaka, the Abhira, at the village (grama) of Rasopadra, for the welfare and comfort of all living beings."

— Epigraphia Indica XVI, p.233

Notes

- Rapson p.92

- Vogel, Jean Ph (1947). India antiqua. Brill Archive. p. 299.

- Rapson CCVIII

- Malwa through the ages, from the earliest times to 1305 A.D. by Kailash Chand Jain p.174

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 90. ISBN 9780195099843.

- Mishra, Susan Verma; Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2016). The Archaeology of Sacred Spaces: The temple in western India, 2nd century BCE–8th century CE. Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 9781317193746.

- Damsteegt, Th (1978). Epigraphical Hybrid Sanskrit: Its Rise, Spread, Characteristics and Relationship to Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. BRILL. p. 201. ISBN 978-9004057258.

- Thomas, F. w (1921). Epigraphia Indica Vol.16. p. 233.

References

- Rapson, "A Catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum. Andhras etc..."