Rose Lamartine Yates

Rose Emma Lamartine Yates (23 February 1875 – 5 November 1954), née Janau, was an English social campaigner and suffragette. She was educated at the Sorbonne and Oxford.

Rose Lamartine Yates | |

|---|---|

Rose Emma Lamartine Yates, 1909 | |

| Born | Rose Emma Lamartine Janau 23 February 1875 London, United Kingdom |

| Died | 5 November 1954 (aged 79) London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Sorbonne, University of Oxford |

| Occupation | Social Activist, Suffragette |

| Spouse(s) | Thomas Lamartine Yates ( m. 1900) |

Together with her lawyer husband she worked for female suffrage from 1908 and during the First World War, and was willing to suffer arrest and incarceration for her beliefs. She travelled widely, giving lectures. She and her husband were also leading members of the Cyclists' Touring Club. After the war she was elected to the London County Council, where she campaigned for equal pay for men and women, better public housing, and the provision of nursery education. She later led the building of an archive of the suffrage campaign.

Life and career

Yates was born in Dalyell Road, Lambeth, London, to a language teacher, Elphège Janau (b. 1847), and his wife, Marie Pauline (1841–1909), both French-born and naturalised British citizens. She was the youngest of their three children. She was educated at high schools in Clapham and Truro, and later at Kassel and the Sorbonne, Paris,[1] and then, from 1896, at Royal Holloway College where she studied modern languages and philology. She passed the Oxford final honours examination in 1899.[2]

In 1900 she married a widower, twenty years her senior, whom she had known since her childhood,[3] Thomas Lamartine Yates (né Swindlehurst, 1849–1929). He was a solicitor, with a successful practice in Chancery Lane.[n 1] Rose studied law with him to help his work and soon became aware of the limitations of women's legal status in those days: 'by the order of man woman is dumb with regard to all the legislative and national affairs'.[3] Eight years after the marriage their only child, Paul (1908–2009), was born; he grew up to become an agricultural economist.[5] Both Yates and her husband were keen cyclists, and were leading members of the Cyclists' Touring Club. In 1907 she was the first woman elected to the governing council of the club. She did not at that point consider herself a suffragette, but soon concluded "on looking into the matter seriously I find I have never been anything else [and] I came to realise that I was and must remain one at whatever personal cost".[1] She joined the recently founded Wimbledon branch of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1908. Her political activism had the full support of her husband, who became a member of the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement and also defended her at her 1909 trial, and acted for other WPSU prisoners, most notably Emily Davison's family at her inquest.[3]

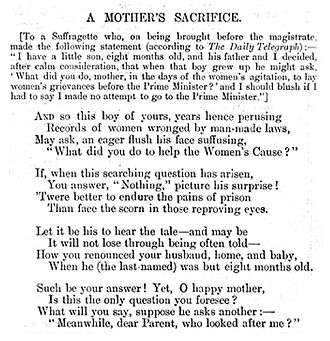

On 24 February 1909 Yates was a member of a deputation led by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence from Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. She was arrested, along with 28 other demonstrators, charged with obstruction and although defended by her husband Tom,[1] she spoke about having the 'courage of her convictions' and said she agreed to "bear whatever punishment you may think me deserving of',[3] and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment.[6] Her son was eight months old at the time, and she had to leave him with her husband. She justified this by considering how she would feel if he asked later, what she had done for the women's cause, if she had done nothing.[3] Punch printed a set of verses criticising her for abandoning him.[7] When she returned home she found her house was decorated in the colours of green, white, violet.[3]

In 1910 Yates became honorary secretary of the Wimbledon WSPU; under her leadership it became one of the most flourishing branches of the organisation. Among those who came to address the branch were Mary Gawthorpe, George Lansbury and an old college friend, Emily Davison, although her invitation to Constance Lytton in April 2011 was declined because of Lytton's poor health.[3] Yates herself also travelled widely, giving lectures.

She and her husband made their house in Merton a refuge where activists released from prison could recuperate. In 1911 Thomas Lamartine Yates was arrested during a demonstration against the government for blocking a bill to allow limited female suffrage. He was not charged, but the publicity damaged his law firm for a time.[1] He made himself available as legal adviser to WSPU prisoners, and in June 1913 he represented the Davison family at the inquest into Emily Davison's death after throwing herself under the king's horse at the Derby. Together with Mary Leigh, Rose was at the dying Davison's bedside, and headed a guard of honour for the funeral procession.[8] Rose carefully kept some of Emily's last possessions for many years, and was sent a letter of thanks from Davison's mother, Margaret, for her 'kind sympathy and appreciation of (her) dear daughter's sacrifice. It was not made in vain. That I feel and take great comfort in the thought.'. She also mentions sharing with neighbours, Tom's touching letter about Emily, which was published in the Daily Sketch.[3]

At the beginning of the First World War the Wimbledon WSPU converted its meeting room and shop into a soup kitchen and opened another in nearby Merton. The war precipitated a split between Yates and the leading suffragette, Emmeline Pankhurst. Under the latter's leadership the WSPU suspended its militant campaign for female suffrage, instead backing the government in the fight against Germany. Yates and others disagreed with this policy. In 1914, together with Alice Green, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Lady Constance Lytton, Ada Wright, raised the fare for Kitty Marion to emigrate to the United States, to avoid the anti-German sentiment rising in the United Kingdom.[9] Yates joined others who broke away to form a new body, the Suffragettes of the WSPU [1] including Mary Leigh. This organisation intended to be militant and national but never achieved a large impact, and like the Independent WSPU it was created in 1916. The SWSPU passed a resolution to concentrate on women's suffrage and to not encourage debate about former WSPU leaders.[10]

In the general election of 1918, in which for the first time, limited female suffrage was granted, Yates was adopted as Labour candidate for the Wimbledon constituency, but both she and the Liberal candidate withdrew shortly before polling.[11] The following year she was elected to the London County Council, representing North Lambeth,[3] and its only independent member. Seven other women candidates stood successfully in the same election.[12] She served for three years, championing equal pay, increased public housing, and the provision of nursery education.[2][3][13]

Yates led the way in building an archive of the suffrage campaign, and in 1939 she opened the Women's Record House in Great Smith Square, London. The building was bombed during the Second World War, but some of its records were saved and are now (2015) in the Suffragette Fellowship collection in the Museum of London.[2]

Yates died at her London home at the age of 79.[2] Her 18th century house, Dorset Hall, was left to the local council and it is now converted to flats.[14]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Thomas and most of his family changed their surname after his father, William Swindlehurst, was convicted of fraud in 1877.[4]

References

- Crawford, pp. 763–764

- Cameron, Gail. "Yates , Rose Emma Lamartine (1875–1954)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University press, retrieved 14 May 2015 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 140, 252, 272, 415, 496, 564. ISBN 9781408844045. OCLC 1016848621.

- "The Frauds on the Artisans' Dwellings Company: The Sentence", The Manchester Guardian, 27 October 1877, p. 8; and Atkinson, Keith, "William Swindlehurst (1824 – c1891) and the Lamartine Yates", History of Shotton, retrieved 14 May 2015

- Maddison, Angus. "Paul Lamartine Yates", RES Newsletter No 147, Royal Economic Society, 2009

- "Woman Suffrage: The Disturbance at Westminster", The Times, 26 February 1909, p. 7

- "A Mother's Sacrifice", Punch, 10 March 1909, p. 172

- Crawford, pp. 340 and 764

- Crawford, Elizabeth (2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge. p. 760. ISBN 1135434026. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Krista Cowman (15 July 2007). Women of the Right Spirit: Paid Organisers of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), 1904-18. Manchester University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7190-7002-0.

- "Last Candidates", The Times, 4 December 1918, p. 10

- "L.C.C. Election Results", The Times, 8 March 1919, p. 14

- "Equal Pay for Women Teachers: Deputation to Mr. Fisher", The Manchester Guardian, 14 May 1920, p. 10

- "Dorset Hall, Kingston Road, Merton Park - Merton Memories Photographic Archive". photoarchive.merton.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

Sources

- Crawford, Elizabeth (1999). The Women's Suffrage Movement : A Reference Guide, 1866-1928. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-84142-031-8.