Rongelap Atoll

Rongelap Atoll /ˈrɒŋɡəlæp/ RONG-gə-lap (Marshallese: Ron̄ļap, [rʷɔŋʷ(ɔ)lˠɑpʲ][1]) is a coral atoll of 61 islands (or motus) in the Pacific Ocean, and forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its total land area is 8 square miles (21 km2). It encloses a lagoon with an area of 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2). It is historically notable for its close proximity to US hydrogen bomb tests in 1954, and was particularly devastated by fallout from the Castle Bravo test. The population was evacuated from Rongelap following the test due to high radiation levels, however according to the most recent census in 2011[2] it has begun to recover with about eighty people living on the atoll.

| |

Rongelap Atoll | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | North Pacific |

| Coordinates | 11°19′N 166°47′E |

| Archipelago | Ralik |

| Total islands | 61 |

| Area | 21 km2 (8.1 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 79 |

| Ethnic groups | Marshallese |

History

The first sighting recorded by Europeans was by Spanish navigator Álvaro de Saavedra on 1 January 1528.[3] Together with Utirik, Ailinginae and Toke atolls, they were charted as Islas de los Reyes (Islands of the Three Wise Kings in Spanish) due to the proximity of Epiphany. Fourteen years later it was visited by the Spanish expedition of Ruy López de Villalobos.[4]

Rongelap Atoll was claimed by the Empire of Germany along with the rest of the Marshall Islands in 1884, and the Germans established a trading outpost. After World War I, the island came under the South Pacific Mandate of the Empire of Japan. Following the end of World War II, Rongelap came under the control of the United States as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.

Nuclear testing impact

Time line

1946: United States Navy evacuates Bikini Atoll Islanders prior to nuclear weapons tests.

March 1, 1954: United States detonates 15-megaton hydrogen bomb (Castle Bravo test) allegedly unaware that fallout will reach Rongelap.[5]

March 3, 1954: US evacuates Rongelap inhabitants to Kwajalein Atoll. Islanders have vomiting, diarrhea, skin burns, and some later experience hair loss.

1955-1957: Internally displaced Rongelapese inhabitants repeatedly request permission from the US Government to return to their atoll.

1957: Atomic Energy Commission declares Rongelap safe for re-habitation. US scientists note: "The habitation of these people on the island will afford most valuable ecological radiation data on human beings."[6]

1958: Rates of Rongelap miscarriages and stillbirths twice the rate of unexposed women.[7]

1963: First thyroid tumors begin to appear.

1971: Independent Japanese medical team invited by Rongelap magistrate denied permission to visit by US citing "visa problems."

1976: Report finds 69% of Rongelap children who were under 10 in 1954 have developed thyroid tumors.

1984: Marshall Islands senator Jeton Anjain requests evacuation assistance from Greenpeace because the US denies the senator's requests for evacuation.

1985: Rainbow Warrior makes three trips to evacuate the Rongelap community to Majetto and Ebeye islands in Kwajalein Atoll.

1986: Nuclear test compensation approved, setting aside a $US150 million trust fund.

1989: United States Department of Energy determines Rongelap safe for habitation.

1994: Independent scientific study finds that depending on dietary restrictions, 25 to 75% of Rongelap population would exceed the 100 mrem maximum annual exposure limit set.

2000: Marshall Islands government submits Change of Circumstances petition asking for significantly more compensation than the $US150m.

2005: Bush Administration determines it has no legal responsibility to provide additional nuclear test compensation.

2007: The Nuclear Claims Tribunal awards Rongelap more than $1 billion as fair damages for its land damage claim, however, since the $US150m trust fund is almost completely depleted this compensation can never be paid.

2009: United States government (Barack Obama administration) reasserts its position that it has satisfactorily compensated Rongelap victims.

The tests

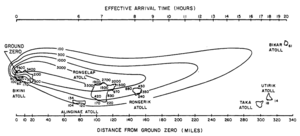

From 1946 through 1958 the United States military conducted numerous atmospheric nuclear weapons tests, including hydrogen bomb tests, primarily at Bikini Atoll, about 120 kilometres (75 mi) from Rongelap Atoll. On March 1, 1954, the testing of the Castle Bravo hydrogen device produced an explosion that was 2½ times more powerful than predicted, and produced unexpected amounts of fallout[8] that resulted in widespread radioactive contamination.[9][10][11] The blast cloud contaminated more than 7,000 square miles (18,000 km2) of the surrounding Pacific Ocean including some of the then inhabited surrounding islands including Rongerik Atoll, Rongelap Atoll (120 kilometres (75 mi) away) and Utirik Atoll.[12]

Irradiated debris fell up to 2 centimetres (0.79 in) deep over the island. A United States military medical team visited the island with geiger counters the day after the fallout, but left without telling the islanders of the danger they had been exposed to.[13] Virtually all the inhabitants experienced severe radiation sickness, including itchiness, sore skin, vomiting, diarrhea, and fatigue. Their symptoms also included burning eyes and swelling of the neck, arms, and legs.[14] The inhabitants were forced to abandon the islands, leaving all their belongings, three days after the test. They were relocated to Kwajalein for medical treatment.[14][15] Six days after the Castle Bravo test, the U.S government set up a secret project to study the medical effects of the weapon on the residents of the Marshall Islands.[16]

The United States was subsequently accused of having used the inhabitants in medical research (without receiving consent) to study the effects of nuclear exposure.[13] Until that time, the United States Atomic Energy Commission had given little thought to the potential impact of widespread fallout contamination and health and ecological impacts beyond the formally designated boundary of the test site.

Failed return to the atoll

In 1957, three years later, the United States government declared the area 'clean and safe' and allowed the islanders to return,[17] though they were told to stick to canned foods and avoid the northern islets of the atoll.[13] Evidence of continued contamination mounted, however, as many residents developed thyroid-tumors,[13][14] and many children died of leukemia.[14] The magistrate of Rongelap, John Anjain, whose own son died of leukemia, appealed for international help, without significant response.

Relocated by Greenpeace

In 1984, Marshall Islands senator, Jeton Anjain approached the environmental group Greenpeace to seek their help in relocating the people of Rongelap and in 1985, 'Operation Exodus' took place. In three trips, the Rainbow Warrior moved approximately 350 people and 100 tonnes (98 long tons; 110 short tons) of building material.[13] to the islets of Mejato and Ebeye on Kwajalein atoll, approximately 180 kilometres (110 mi) away. The operation took 11 days, moving everyone from 80-year-olds to newborns, their homes and their belongings. Ebeye is significantly smaller than the islands of Rongelap, and joblessness, suicide, and overcrowding have proven to be problems following the resettlement.

Compensation awarded

In September 1996, the United States Department of the Interior signed a $45 million resettlement agreement with the islanders, stipulating that the islanders themselves will scrape off a few inches of Rongelap's still contaminated surface. However, this is an operation deemed impossible by some critics. In recent years, James Matayoshi, the mayor of Rongelap, claimed that the cleanup was successful and envisioned a new promising future for the inhabitants and for tourists.[18] Scientific measurements made in August 2014 verified a safe level of radiation on Rongelap.[19]

Aftermath

In 1991, the People of Rongelap and Jeton Anjain received the Right Livelihood Award "for their steadfast struggle against United States nuclear policy in support of their right to live on an unpolluted Rongelap island."

Education

Marshall Islands Public School System operates Mejatto Elementary School, which serves descendants of the community in Mejatto that resided in Rongelap Atoll.[20]

References

- "Marshallese-English Dictionary - Place Name Index". www.trussel2.com.

- "Census data" (PDF). www.doi.gov. 2011. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- Brand, Donald D. The Pacific Basin: A History of its Geographical Explorations. The American Geographical Society, New York, 1967, p.121.

- Sharp, Andrew. The discovery of the Pacific Islands. Oxford, 1960, p. 23.

- United States National Research Council Committee on Radiological Safety in the Marshall Islands (1994). Radiological Assessments for Resettlement of Rongelap in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. National Academies Press. pp. Introduction.

- Johnson, Giff (February 1979). "Micronesia: America's 'strategic' trust". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: 15.

- De Ishtar, Zohl (May 2003). "Poisoned Lives, Contaminated Lands: Marshall Islanders Are Paying a High Price for the United States Nuclear Arsenal". Seattle Journal for Social Justice. 2 (1): 291.

- "The Bikini Atoll Survey "Operation Crossroads," 1946-47". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Kaleem, Muhammad (2000). "Energy of a Nuclear Explosion". The Physics Factbook. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- Lorna Arnold and Mark Smith. (2006). Britain, Australia and the Bomb, Palgrave Press, p. 77.

- John Bellamy Foster (2009). The Ecological Revolution: Making Peace with the Planet, Monthly Review Press, New York, p. 73.

- Titus, A. Costandina (2001). Bombs in the Backyard Atomic Testing and American Politics. Reno: University of Nevada.

- "The evacuation of Rongelap". Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- Isobelle Gidley and Richard Shears (1986). The Rainbow Warrior Affair, Unwin, p. 155.

- Gerald H. Clarfield and William M. Wiecek (1984). Nuclear America: Military and Civilian Nuclear Power in the United States 1940-1980, Harper & Row, New York, p. 207.

- "Establishment of Program 4 and Project 4.1 in Castle" (PDF). James Reeves to Frank D. Peel. 11 March 1954.Archive index at the Wayback Machine

- McCool, Woodford C. (1957-02-06), Return of Rongelapese to their Home Island - Note by the Secretary (PDF), United States Atomic Energy Commission, archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007, retrieved 2007-11-07

- "Situs Poker Online, Situs Poker, Poker Online, Judi Poker". 202.95.10.165.

- Lestch, Corinne. "Discovering Nuclear Studies Through the Marshall Islands". Columbia College. Columbia University. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "Public Schools ." Marshall Islands Public School System. Retrieved on February 21, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rongelap Atoll. |

- Marshall Islands site

- Entry at Oceandots.com at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2010)

- Rongelap Atoll official site

- Radio Bikini : Oscar-nominated 1987 documentary on the 1946 atomic bomb tests on Bikini Atoll and the effects on the Bikinians as well as the US sailors who witnessed the tests.

- Het Einde van de Wereld The End of the World (1995/VPRO-TV/Theo Uittenbogaard) a Dutch documentary on the history of the people of the island Rongelap, who were evacuated due to fallout from the Bikini nuclear tests and their (inc. John Anjain) hearing by a Senate Committee in Washington DC