Rock City, Kansas

Rock City is a park located on hillsides overlooking the Solomon River in Ottawa County, Kansas. It is 3.6 miles south of Minneapolis, Kansas and just over 0.5 mile west of Kansas highway K-106 and the Minneapolis City County Airport on Ivy Road. In a patch of prairie about 500 meters (1600 feet) long and 40 meters (130 feet) wide, Rock City contains three clusters of large spherical boulders. These three clusters contain a total of 200 spherical boulders. It has been designated as a National Natural Landmark.

| Rock City | |

|---|---|

Rock City, 2006 | |

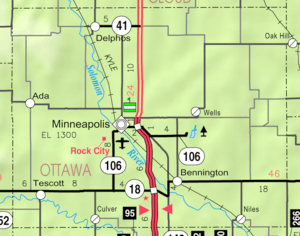

Map showing location of Rock City | |

| Location | Minneapolis, Kansas, Ottawa, Kansas, Kansas, United States |

| Coordinates | 39°5′27.20″N 97°44′7.99″W |

| Elevation | 1,276 ft (389 m)[1] |

| Website | Web Site |

| Designated | 1976 |

The park, owned by a non-profit corporation, has a visitor center and picnic tables. A small admission fee, which is used to maintain this park, is charged.

The remarkable size and spherical shape of these rock formation was first noted by Bell.[2] Later, these boulders were either noted or described by Gould,[3] Landes,[4] Shaffer,[5] Ward,[6] and Swineford.[7] Shaffer[5] was the first person to map the distribution of these boulders at Rock City and investigate their petrography in detail.[8]

Physical characteristics

The large spherical boulders in Rock City are giant calcite-cemented concretions, typically called "cannonball concretions" because of their shape. They range in diameter from 3 to 6 meters (10 to 20 feet) with the average diameter being 3.6 meters (12 feet). These concretions lie 2 to 8 meters (6.6 to 26 feet) apart.[8] Similar giant calcite-cemented concretions have also been found in a quartzite quarry within Lincoln County and in exposures of the similar age sandstones in Utah and Wyoming.[8][9]

These boulders consist of well-sorted, medium-grained sandstone, which is tightly cemented by calcite. The sandstone consists of more than 95 percent quartz sand. About 20 percent of the original sandstone, mostly feldspar grains, has been replaced by the calcite. Pyrite, which is now oxidized to goethite, occurs within the calcite cement of these concretions as microscopic crystals and very small, knobby concretions. The pyrite concretions typically are about 30 cm (1 foot) in diameter. Also, included within these calcite concretions are smaller calcite concretions, which have been engulfed by the growth of the larger concretions.[8]

The host rock, which contained these spherical boulders, consists of well-sorted, medium-grained, highly porous, and friable sandstone. Being only weakly indurated by small amounts of iron oxide, sometimes seen as Liesegang rings (banding) at Rock City, it is considerably softer and very much more easily eroded than the calcite concretions. The sand comprising it accumulated within a river channel, which is part of the Dakota Sandstone, which accumulated within a low-lying coastal plain. Differential cementation and later erosion of cross-bedding inherited from the riverine sand, in which these concretions occur, created the "ornamentation", which these concretions exhibit.[8]

Origin

In the past, the origin of the spherical boulders found at Rock City had been erroneously interpreted as glacial boulders, corals, concretionary masses of limestone, and normal erosional remnants of sandstone. Shaffer[5] was the first person to recognize them as calcite-cemented concretions. From a detailed examination of the mineralogy of these concretions and the carbon and oxygen isotopes of the calcite cement comprising them, McBride and others[8] concluded that they formed as the result of diffusion of calcium through and precipitation of calcite within the sandstone containing them after being deeply buried. The carbon and calcium comprising these concretions came either from marine limestone, shells, anhydrite, or some combination of these in addition to bicarbonate derived from oxidized methane from strata outside of, but hydrologically connected to, the Dakota Sandstone. After the formation of the concretions, differential erosion of the considerably softer sandstone surrounding them exposed as free-standing boulders.[8]

Gallery

Tree at Rock City

Tree at Rock City A turtle-shaped rock

A turtle-shaped rock A large, round rock

A large, round rock Trees at Rock City

Trees at Rock City Hesperis matronalis growing by a rock in May

Hesperis matronalis growing by a rock in May Looking towards Minneapolis, KS across rippling wheat fields in May

Looking towards Minneapolis, KS across rippling wheat fields in May

See also

Other rock formations in Kansas:

References

- "Rock City". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Bell, W.T., 1901, The remarkable concretions of Ottawa County, Kansas, American Journal of Science, 4th Series, v. 11, p. 315-316.

- Gould, C.N., 1901, The Dakota Cretaceous of Kansas and Nebraska, Kansas Academy of Science, v. 17, p. 122-178.

- Landes, K.K., 1935, Scenic Kansas, Geological Survey of Kansas Bulletin, n. 36, 55 p.

- Shaffer, H.L., 1937, Concretions in the Dakota Sandstone, Compass, v. 17, p. 87-90.

- Ward, H.K., 1938, Concretions of Rock City. Mineralogist, v. 6, p. 23-24.

- Swineford, Ada (1947). Cemented sandstones of the Dakota and Kiowa formations in Kansas. Geological Survey of Kansas Bulletin. OCLC 5051056.

- McBride, Earle F; Milliken, Kitty L (2006). "Giant calcite-cemented concretions, Dakota Formation, central Kansas, USA". Sedimentology. 53 (5): 1161–79. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.2006.00813.x.

- McBride, E. F; Picard, M. D; Milliken, K. L (2003). "Calcite-Cemented Concretions in Cretaceous Sandstone, Wyoming and Utah, U.S.A". Journal of Sedimentary Research. 73 (3): 462–83. doi:10.1306/111602730462.

External links

- Rock City Park, Kansas Hours, prices, history

- Kansas Geological Survey, nd, Smoky Hills—Places to Visit

- Rock City, Minneapolis, Kansas

- Rock City

- Biek, B., 2002, Concretions and Nodules in North Dakota North Dakota Geological Survey, Bismarck, North Dakota. Explains how concretions are created.

- Dietrich, R.V., 2002, Carbonate Concretions--A Bibliography, The Wayback Machine. and PDF file of Carbonate Concretions--A Bibliography, CMU Online Digital Object Repository, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan.

- Hansen, M.C., 1994, Ohio Shale Concretions PDF version, 270 KB Ohio Division of Geological Survey GeoFacts n. 4, pp. 1–2.

- Heinrich, P.V., 2007, The Giant Concretions of Rock City Kansas PDF version, 836 KB BackBender's Gazette. vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 6–12.

- Kansas Geological Survey, 2004, Educational Resources, Photos from Ottawa County

- Ottawa County Map, KDOT

- Rock Climbing at Rock City