Methocarbamol

Methocarbamol, sold under the brand name Robaxin among others, is a medication used for short-term musculoskeletal pain.[4][5] It may be used together with rest, physical therapy, and pain medication.[4][6][7] It is less preferred in low back pain.[4] It has limited use for rheumatoid arthritis and cerebral palsy.[4][8] Effects generally begin within half an hour.[4] It is taken by mouth or injection into a vein.[4]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Robaxin, Marbaxin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682579 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1.14–1.24 hours[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.751 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

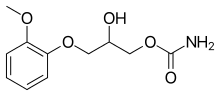

| Formula | C11H15NO5 |

| Molar mass | 241.243 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effect include headaches, sleepiness, dizziness.[4][9] Serious side effects may include anaphylaxis, liver problems, confusion, and seizures.[5] Use is not recommended in pregnancy and breastfeeding.[4][5] Use by the elderly is considered high risk.[4] Methocarbamol is a centrally acting muscle relaxant.[4] How it works is unclear, but it does not appear to affect muscles directly.[4]

Methocarbamol was approved for medical use in the United States in 1957.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[4][5] It is relatively inexpensive as of 2016.[10] In 2017, it was the 178th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[11][12]

Medical use

Methocarbamol is a muscle relaxant used to treat acute, painful musculoskeletal spasms in a variety of musculoskeletal conditions.[13] However, there is limited and inconsistent published research on the medication's efficacy and safety in treating musculoskeletal conditions, primarily neck and back pain.[13]

Methocarbamol injection may have a beneficial effect in the control of the neuromuscular spasms of tetanus.[7] It does not, however, replace the current treatment regimen.[7]

It is not useful in chronic neurological disorders, such as cerebral palsy or other dyskinesias.[4]

Currently, there is some suggestion that muscle relaxants may improve the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis; however, there is insufficient data to prove its effectiveness as well as answer concerns regarding optimal dosing, choice of muscle relaxant, adverse effects, and functional status.[8]

Comparison to similar agents

The clinical effectiveness of methocarbamol compared to other muscle relaxants is not well-known.[13] One trial of methocarbamol versus cyclobenzaprine, a well-studied muscle relaxant, in those with localized muscle spasm found there was no significant differences in their effects on improved muscle spasm, limitation of motion, or limitation of daily activities.[13]

Contraindications

There are few contraindications to methocarbamol. They include:

- Hypersensitivity to methocarbamol or to any of the injection components.[7]

- Suspected kidney failure or renal pathology due to large content of polyethylene glycol 300 that can increase pre-existing acidosis and urea retention.[7]

Side effects

Methocarbamol is a centrally acting skeletal muscle relaxant that has significant adverse effects, especially on the central nervous system.[4]

Potential side effects of methocarbamol include:

- Most commonly drowsiness, blurred vision, headache, nausea, and skin rash.[9]

- Possible clumsiness (ataxia), upset stomach, flushing, mood changes, trouble urinating, itchiness, and fever.[14][15]

- Both tachycardia (fast heart rate) and bradycardia (slow heart rate) have been reported.[15]

- Hypersensitivity reactions and anaphylatic reactions are also reported.[6][7]

- May cause respiratory depression when combined with benzodiazepines, barbiturates, codeine, or other muscle relaxants.[16]

- May cause urine to turn black, blue or green.[14]

While the product label states that methocarbamol can cause jaundice, there is minimal evidence to suggest that methocarbamol causes liver damage.[9] During clinical trials of methocarbamol, there were no laboratory measurements of liver damage indicators, such as serum aminotransferase (AST/ALT) levels, to confirm hepatotoxicity.[9] Although unlikely, it is impossible to rule out that methocarbamol may cause mild liver injury with use.[9]

Elderly

Skeletal muscle relaxants are associated with an increased risk of injury among older adults.[17] Methocarbamol appeared to be less sedating than other muscle relaxants, most notably cyclobenzaprine, but had similar increased risk of injury.[16][17] The medication was listed on the 2012 Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults and is considered to be a high-risk medication for the elderly.[18]

Pregnancy

Methocarbamol is labeled by the FDA as a pregnancy category C medication.[7] The teratogenic effects of the medication are not known and should be given to pregnant women only when clearly indicated.[7]

Overdose

There is limited information available on the acute toxicity of methocarbamol.[6][7] Overdose is used frequently in conjunction with CNS depressants such as alcohol or benzodiazepines and will have symptoms of nausea, drowsiness, blurred vision, hypotension, seizures, and coma.[7] There are reported deaths with an overdose of methocarbamol alone or in the presence of other CNS depressants.[6][7]

Abuse

Unlike other carbamates such as meprobamate and its prodrug carisoprodol, methocarbamol has greatly reduced abuse potential.[19] Studies comparing it to the benzodiazepine lorazepam and the antihistamine diphenhydramine, along with placebo, find that methocarbamol produces increased "liking" responses and some sedative-like effects; however, at higher doses dysphoria is reported.[19] It is considered to have an abuse profile similar to, but weaker than, lorazepam.[19]

Interactions

Methocarbamol may inhibit the effects of pyridostigmine bromide.[6][7] Therefore, methocarbamol should be used with caution in those with myasthenia gravis taking anticholinesterase medications.[7]

Methocarbamol may disrupt certain screening tests as it can cause color interference in laboratory tests for 5-hydroxy-indoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and in urinary testing for vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) using the Gitlow method.[7]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

The mechanism of action of methocarbamol has not currently been established.[4] Its effect is thought to be localized to the central nervous system rather than a direct effect on skeletal muscles.[4] It has no effect on the motor end plate or the peripheral nerve fiber.[7] The efficacy of the medication is likely related to its sedative effect.[4] Alternatively, methocarbamol may act via inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, similarly to carbamate.[20]

Pharmacokinetics

In healthy individuals, the plasma clearance of methocarbamol ranges between 0.20 and 0.80 L/h/kg.[7] The mean plasma elimination half-life ranges between 1 and 2 hours, and the plasma protein binding ranges between 46% and 50%.[7] The elimination half-life was longer in the elderly, those with kidney problems, and those with liver problems.[7]

Metabolism

Methocarbamol is the carbamate derivative of guaifenesin, but does not produce guaifenesin as a metabolite, because the carbamate bond is not hydrolyzed metabolically;[9][7] its metabolism is by Phase I ring hydroxylation and O-demethylation, followed by Phase II conjugation.[7] All the major metabolites are unhydrolyzed carbamates.[21][22] Small amounts of unchanged methocarbamol are also excreted in the urine.[6][7]

Society and culture

Methocarbamol was approved as a muscle relaxant for acute, painful musculoskeletal conditions in the United States in 1957.[9] Muscle relaxants are widely used to treat low back pain, one of the most frequent health problems in industrialized countries. Currently, there are more than 3 million prescriptions filled yearly.[9] Methocarbamol and orphenadrine are each used in more than 250,000 U.S. emergency department visits for lower back pain each year.[23] In the United States, low back pain is the fifth most common reason for all physician visits and the second most common symptomatic reason.[24] In 80% of primary care visits for low back pain, at least one medication was prescribed at the initial office visit and more than one third were prescribed two or more medications.[25] The most commonly prescribed drugs for low back pain included skeletal muscle relaxants.[26] Cyclobenzaprine and methocarbamol are on the U.S. Medicare formulary, which may account for the higher use of these products.[17]

Economics

The generic formulation of the medication is relatively inexpensive, costing less than the alternative metaxalone in 2016.[27][10] In the UK, the NHS pays about £13 for 100 tablets of 750 mg of methocarbamol as of 2019.[5] In the US the wholesale cost of this quantity is about US$10 as of 2020.[28]

Marketing

Methocarbamol without other ingredients is sold under the brand name Robaxin in the U.K., U.S., Canada and South Africa; it is marketed as Lumirelax in France, Ortoton in Germany and many other names worldwide.[29] In combination with other active ingredients it is sold under other names: with acetaminophen (paracetamol), under trade names Robaxacet and Tylenol Body Pain Night; with ibuprofen as Robax Platinum; with acetylsalicylic acid as Robaxisal in the U.S. and Canada.[30][31] However, in Spain the tradename Robaxisal is used for the paracetamol combination instead of Robaxacet. These combinations are also available from independent manufacturers under generic names.

Research

Although opioids are a typically first line in treatment of severe pain, several trials suggest that methocarbamol may improve recovery and decrease hospital length of stay in those with muscles spasms associated with rib fractures.[32][33][34] However, methocarbamol was less useful in the treatment of acute traumatic pain in general.[35]

Long-term studies evaluating the risk of development of cancer in using methocarbamol have not been performed.[6][7] There are currently no studies evaluating the effect of methocarbamol on mutagenesis or fertility.[6][7]

The safety and efficacy of methocarbamol has not been established in pediatric individuals below the age of 16 except in tetanus.[6][7]

References

- "Methocarbamol Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Robaxin-750 - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 8 August 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Sica DA, Comstock TJ, Davis J, Manning L, Powell R, Melikian A, Wright G (1990). "Pharmacokinetics and protein binding of methocarbamol in renal insufficiency and normals". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 39 (2): 193–4. doi:10.1007/BF00280060. PMID 2253675.

- "Methocarbamol Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 1093. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "Robaxin- methocarbamol tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 18 July 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Robaxin- methocarbamol injection". DailyMed. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Richards, Bethan L.; Whittle, Samuel L.; Buchbinder, Rachelle (18 January 2012). "Muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD008922. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008922.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 22258993.

- "Methocarbamol". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 30 January 2017. PMID 31643609.

- Fine, Perry G. (2016). The Hospice Companion: Best Practices for Interdisciplinary Care of Advanced Illness. Oxford University Press. p. PT146. ISBN 978-0-19-045692-4.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Methocarbamol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Chou, Roger; Peterson, Kim; Helfand, Mark (August 2004). "Comparative efficacy and safety of skeletal muscle relaxants for spasticity and musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 28 (2): 140–175. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.05.002. ISSN 0885-3924. PMID 15276195.

- "Methocarbamol". MedlinePlus. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Methocarbamol Side Effects: Common, Severe, Long Term". Drugs.com. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- See, Sharon; Ginzburg, Regina (1 August 2008). "Choosing a skeletal muscle relaxant". American Family Physician. 78 (3): 365–70. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 18711953.

- Spence, Michele M.; Shin, Patrick J.; Lee, Eric A.; Gibbs, Nancy E. (July 2013). "Risk of injury associated with skeletal muscle relaxant use in older adults". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 47 (7–8): 993–8. doi:10.1345/aph.1R735. ISSN 1542-6270. PMID 23821610.

- "Beers Criteria Medication List". DCRI. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Preston KL, Wolf B, Guarino JJ, Griffiths RR (1992). "Subjective and behavioral effects of diphenhydramine, lorazepam and methocarbamol: evaluation of abuse liability". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 262 (2): 707–20. PMID 1501118.

- PubChem. "Methocarbamol". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Methocarbamol. In: DRUGDEX System [intranet database]. Greenwood Village, Colorado: Thomson Healthcare; c1974–2009 [cited 2009 Feb 10].

- Bruce RB, Turnbull LB, Newman JH (January 1971). "Metabolism of methocarbamol in the rat, dog, and human". J Pharm Sci. 60 (1): 104–6. doi:10.1002/jps.2600600120. PMID 5548215.

- Friedman BW, Cisewski D, Irizarry E, Davitt M, Solorzano C, Nassery A, et al. (March 2018). "A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Naproxen With or Without Orphenadrine or Methocarbamol for Acute Low Back Pain". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 71 (3): 348–356.e5. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.09.031. ISSN 1097-6760. PMC 5820149. PMID 29089169.

- Chou, Roger; Huffman, Laurie Hoyt (2 October 2007). "Medications for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline". Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (7): 505–14. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00008. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 17909211.

- Cherkin, D. C.; Wheeler, K. J.; Barlow, W.; Deyo, R. A. (1 March 1998). "Medication use for low back pain in primary care". Spine. 23 (5): 607–14. doi:10.1097/00007632-199803010-00015. ISSN 0362-2436. PMID 9530793.

- Luo, Xuemei; Pietrobon, Ricardo; Curtis, Lesley H.; Hey, Lloyd A. (1 December 2004). "Prescription of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants for back pain in the United States". Spine. 29 (23): E531–7. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000146453.76528.7c. ISSN 1528-1159. PMID 15564901.

- Robbins, Lawrence D. (2013). Management of Headache and Headache Medications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. PT147. ISBN 978-1-4612-2124-1.

- "NADAC as of 2020-04-15 | Data.Medicaid.gov". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Methocarbamol". Drugs.com. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- "New Drugs and Indications Reviewed at the May 2003 DEC Meeting" (PDF). ESI Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- "Tylenol Body Pain Night Overview and Dosage". Tylenol Canada. Archived from the original (website) on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- Patanwala, Asad E.; Aljuhani, Ohoud; Kopp, Brian J.; Erstad, Brian L. (October 2017). "Methocarbamol use is associated with decreased hospital length of stay in trauma patients with closed rib fractures". The American Journal of Surgery. 214 (4): 738–42. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.01.003. ISSN 0002-9610. PMID 28088301.

- Deloney, Lindsay; Smith, Melanie; Carter, Cassandra; Privette, Alicia; Leon, Stuart; Eriksson, Evert (January 2020). "946: Methocarbamol reduces opioid use and length of stay in young adults with traumatic rib fractures". Critical Care Medicine. 48 (1): 452. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000633320.62811.06. ISSN 0090-3493.

- Smith, Melanie; Deloney, Lindsay; Carter, Cassandra; Leon, Stuart; Privette, Alicia; Eriksson, Evert (January 2020). "1759: Use of methocarbamol in geriatric patients with rib fractures is associated with improved outcomes". Critical Care Medicine. 48 (1): 854. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000649332.10326.98. ISSN 0090-3493.

- Aljuhani, Ohoud; Kopp, Brian J.; Patanwala, Asad E. (2017). "Effect of Methocarbamol on Acute Pain After Traumatic Injury". American Journal of Therapeutics. 24 (2): e202–6. doi:10.1097/mjt.0000000000000364. ISSN 1075-2765. PMID 26469684.

External links

- "Methocarbamol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.