Risdon Cove

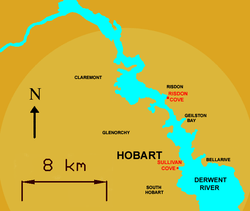

Risdon Cove is a cove located on the east bank of the Derwent River, approximately 7 kilometres (4 mi) north of Hobart, Tasmania. It was the site of the first British settlement in Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, the smallest Australian state. The cove was named by John Hayes,[1] who mapped the river in the ship Duke of Clarence in 1794, after his second officer William Bellamy Risdon.

In 1803 Lieutenant John Bowen was sent to establish a settlement in Van Diemen's Land. On the advice of the explorer George Bass he had chosen Risdon Cove. While the site was a good one from a defensive point of view, the soil was poor and water scarce. Lady Nelson anchored at Risdon on the eastern shore of the Derwent River on Wednesday 8 September 1803, five days before the whaler Albion arrived with Lt. Bowen on board. The 49 people aboard the Lady Nelson and Albion made a curious party of soldiers, sailors, settlers and convicts.

In 1804 Lieutenant Colonel David Collins arrived in the Derwent from Port Phillip on Ocean. Within a few days he rejected Risdon Cove as a suitable settlement site, for its inadequate source of fresh water, and moved his party across the river to Sullivans Cove. The military and convicts disembarked from Ocean near Hunter Island on the 20–21 February 1804 and thus beginning what is now Hobart. Lady Nelson landed the free settlers at New Town Bay on 22 February.

One of the first land grants at Risdon Cove was made to Dr William F A I'Anson, the chief surgeon who arrived with Lieutenant-Governor Collins in 1804.[2]

3 May 1804

The original records show that a large group of Aborigines blundered into the British settlement. The soldiers mistakenly thought they were under attack and killed some of the intruders.

About 300 aboriginals, men, women and children, who had banded together approached the Risdon Cove settlement whilst occupied on a kangaroo hunt. The Aborigines had arrived at the settlement and some were justifiably upset by the presence of the colonists. There had been no widespread aggression, but if their displeasure spread and escalated, Lt. Moore, the commanding officer at the time, and his dozen or so soldiers, could not be expected to be able to protect the settlement from a mob of such size. The soldiers were therefore ordered to fire a carronade (a short-barrel, heavy calibre naval cannon known to sailors as "the smasher") in an attempt to disperse the aboriginals; it is not known if this was a blank round, although some allege grape shot was used to explain an alleged but uncorroborated high figure of deaths. In addition, two soldiers fired muskets in protection of a Risdon Cove settler being beaten on his farm by aboriginals carrying waddies (clubs). These soldiers killed one aboriginal outright, and mortally wounded another, who was later found dead in a valley. Moore's account lists three killed and some wounded. It is therefore known that in the conflict some aboriginals were killed, and that the colonists "had reason to Suppose more were wounded, as one was seen to be taken away bleeding".[3] It is also known that an infant boy about 2–3 years old was left behind in what was viewed as a "retreat from a hostile attempt made upon the borders of the settlement".[4]

"There were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded" according to the Edward White, an Irish convict who later spoke before a committee of inquiry nearly 30 years later in 1830, but could not give exact figures.[5] White alleged to have been an eyewitness, although he was working in a creek bed where the escarpment prevented him from viewing events. Claiming to be the first to see the approaching aboriginals, he also said that "the natives did not threaten me; I was not afraid of them; (they) did not attack the soldiers; they would not have molested them; they had no spears with them; only waddies".[5] That they had no spears with them is questionable, and his claims need to be assessed with caution. His contemporaries had believed the approach to be a potential attack by a group of aboriginals that greatly outnumbered the colonists in the area, and spoke of "an attack the natives made", their "hostile Appearance", and "that their design was to attack us".[3]

A macabre postscript to the story was an allegation that the bones of some of the Aborigines were shipped to Sydney in two casks.[5] There is no documentary evidence of this.

20th century

The site at Risdon Cove was farmed until 1946. By the 150th anniversary celebrations (September 1954) land had been acquired by the State Government to add to the reserve.[6] The hand-over of the Risdon Cove site, which includes the Bowen Memorial, was part of the Aboriginal Lands Bill. The transfer occurred on 11 December 1995, and since then Aboriginal Tasmanians have creditably maintained and developed the site as a cultural and educational facility.[6]

References

- Roe, Margriet (1966). "Hayes, Sir John (1768–1831)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 26 January 2012 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- "Prestige Philately and Mossgreen". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- W.F. Refshauge (2007). "An analytical approach to the events at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, June 2007.

- "NATIVES". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842). NSW: National Library of Australia. 2 September 1804. p. 2. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Phillip Tardif (6 April 2003). "So who's fabricating the history of Aborigines?". Melbourne: The Age, 6 April 2003.

- Risdon Cove History. Members.iinet.net.au. Retrieved on 2013-09-27.