Riddles (Finnic)

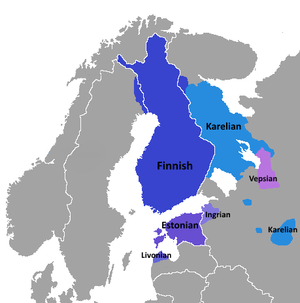

The corpus of traditional riddles from the Finnic-speaking world (including the modern Finland, Estonia, and parts of Western Russia) is fairly unitary, though eastern Finnish-speaking regions show particular influence of Russian Orthodox Christianity and Slavonic riddle culture.[1] The Finnish for 'riddle' is arvoitus (pl. arvoitukset), related to the verb arvata ('guess').

Riddles provide some of the first surviving evidence for Finnic literature.[2] Finnic riddles are noteworthy in relation to the rest of the world's oral riddle canon for their original imagery, their abundance of sexual riddles, and the interesting collision of influences from east and west;[3] along with the attestation in some regions of an elaborate riddle-game.[4]

The archives of the Finnish Literature Society contain texts of 117,300 Finnish-language riddles collected from oral tradition, some of which are in Kalevala metre;[5] meanwhile, the Estonian Folklore Archives contain around 130,000 older traditional riddles, along with about 45,000 other riddle-type folklore, such as conundra, initial letter puzzles, droodles, etc.[6]

Form

Most traditional Finnish and Estonian riddles consist of a simple pair of statements, like 'kraatari menee läpi kylän, eikä sanoo hyvää huomenta' ('the tailor goes through the village without saying good morning'), whose answer is 'needle and thread without an end knot' (collected in Naantali in 1891); the common 'isä vielä syntymässä, kuin lapset laajalle liikkuu' ('the father is just being born when the sons are already fighting a war'), to which the answer is 'fire and sparks' (this example being from Joroinen from 1888);[7] or the Estonian 'Üks hani, neli nina?' ('One goose, four noses?'), to which the answer is 'padi' ('a pillow’).[8] Very few include an explicit question like 'what is the thing that...?'[9] They are generally set apart from everyday language by distinctive syntactic tendencies.[10]

Many riddles are in Kalevala metre, such as this example of the internationally popular 'Ox-Team Riddle' collected in Loimaa in 1891:[11]

Kontio korvesta tulee |

From the backwoods comes a bruin |

At times riddles allude to traditional mythology, mostly through passing reference to people, beings or places,[12] and to other poetic genres such as elegy or charms.[13]

Early attestations

Records of riddles provide some of the earliest evidence for Finnish-language literature: the first grammar of Finnish, Linguae Finnicae brevis institutio by Eskil Petraeus (1649) included eight illustrative riddles, including 'caxi cullaista cuckoi ylitze orren tappelewat' ('two golden cocks fight over a beam'), the answer to which is 'eyes and nose', and 'Pidempi pitke puuta | matalambi maan ruoho' ('taller than a tall tree | lower than the grass of the earth'), to which the answer is 'a road'.[14] Later, in 1783, Cristfried Ganander published 378 riddles under the title Aenigmata Fennica, Suomalaiset Arwotuxet Wastausten kansa, arguing that 'one can see from these riddles that the Finnish people think and describe as accurately as any other nation, and that their brains are no worse than others'. And from these riddles we also learn of the richness and aptness of the Finnish language in explaining all manner of things'.[15]

Social contexts

Riddles were a common form of entertainment for the whole household in the Finnish-speaking world into the 1910s and 1920s, but new entertainments, the obsolescence of the traditional riddle stock caused by changing material and economic norms, the increasing unfashionability of Kalevala-metre, and changes to family structures associated with urbanisation, led to their demise as a mainstream form of entertainment.[16] Riddles were generally learned by heart, and often their solutions too, such that guessing a riddle was not always strictly a test of wits.[17]

Much of the Finnish region (but not Estonia) also attests to a distinctive riddle game, alluded to already in Ganander's 1783 collection,

in which the unsuccessful guesser is sent to a place called Hyvölä, Himola, Hymylä ('Smileville'), Huikkola or Hölmölä ('Numskull place'). ... The participants may agree among themselves after how many unsuccessful guesses one must leave for that place "to get some wits". ... The course of the game appears in actual fact to have been such that the unsuccessful participant was dressed into funny clothing and was sent into the courtyard, vestibule, or kitchen corner. A part of the players can now pretend to be Hymylä folk who discuss the coming of the stranger and answer his questions. At his destination the guesser is ... offered the most repulsive foods and left-overs. He is made to wash himself, e.g., in a tar barrel and dry himself with feathers ... The next act of the farce is once again in the home living room: the stranger has returned and recounts his journey. This scene apparently depends much upon the respondent's inventiveness, and he can compensate for his earlier failure by making his listeners laugh at his new inventions.[18]

Sexual riddles were not generally presented at household evening gatherings, but rather at gatherings along the lines of age, gender, or occupation.[19] Examples of sexual riddles include 'kaks partasuuta miestä vetelee yhteistä sikaaria' ('two bearded men smoking a cigar together'), to which the answer is 'naiminen' ('fucking') and 'kaksi tikkaa takoo yhden ämmän persieen' ('two woodpeckers jab one woman's cunt'), to which the answer is 'huhmar ja kaksi puista petkeltä' ('mortar and two wooden pestles').[20]

Mythic references in riddles

Though not particularly common, riddles that refer to figures of traditional Finnic mythology have excited considerable interest among scholars. This riddle is an example:

Tuhatsilmä Tuonen neito, |

The thousand-eyed maid of Tuoni, |

The answer is 'rain', but might once have been 'fishing net'. The poem alludes to the traditional god of the underworld, Tuoni, and recalls Finnish elegiac verse.[21]

The following riddles require knowledge of the images and cosmology of Kalevala-poetry, particularly the healing incantations called synnyt:

Iski tulta Ilmarinen, välähytti Väinämöinen. |

Ilmarinen struck fire, Väinämöinen flashed. |

Mytty mättähän takainen, kiekura kiven alainen, kieko kannon juurinen. |

Bunched up behind the hummock, curled up under a stone, a disc at the foot of a stump. |

Major editions

- Elias Lönnrot, Suomen kansan arwoituksia: ynnä 135 Wiron arwoituksen kanssa, 2nd edn (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1851), http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/31144, https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1LUWAAAAYAAJ&. First published in 1844; the expanded 1851 edition contains 2,224 riddles (including 135 from Estonia) and 190 variants. Sources for the riddles are not stated.

- M. J. Eisen, Eesti mōistatused (Tartu 1913). The seminal scholarly collection of Estonian riddles.

- Suomen kansan arvoituskirja, ed. by Martti Haavio and Jouko Hautala (1946). Founded on work by Antti Aarne and Kaarle Krohn, based on the Finnish Literature Society archive, and aimed at the general public, but stating places of acquisition for the texts.

- Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977). Contains all those texts in the archive of the Finnish Literature Society for which at least two independent variants exist and which the editors judged to be 'true riddles', along with English paraphrases: 1248 in all.[24]

- Tere teele, tere meele, tere egalõ talolõ: Valik lõunaeesti mõistatusi, ed. by Arvo Krikmann (Tartu: [Eesti kirjandusmuuseum], 2000), a collection of south-Estonian riddles.

- Eesti mõistatused = Aenigmata Estonica, ed. by A. Hussar, A. Krikmann, R. Saukas, P. Voolaid, A. Krikmann, and R. Saukas, Monumenta Estoniae antiquae, 4, 3 vols (Tartu: Eesti keele sihtasutus, 2001–13), http://www.folklore.ee/moistatused/. The principal edition of traditional Estonian riddles in both print and database forms, containing 2,800 entries and 95,751 individual witnesses.

- Estonian peripheral riddles:

- Estonian Droodles, ed. by Piret Voolaid, http://www.folklore.ee/Droodles/. Includes all 7,200 Estonian droodles collected before 1996.

- Eesti piltmõistatused, ed. by Piret Voolaid, http://www.folklore.ee/Reebus/. Database of all Estonian rebuses collected up to 1996.

- Eesti keerdküsimused, ed. by Piret Voolaid, http://www.folklore.ee/Keerdkys/. Database of over 25,000 Estonian conundra, of the type 'Kuidas sa tead, et elevant on voodi all? – Voodi on lae all' (‘How do you know the elephant is under the bed? – The bed is under the ceiling’).

- Eesti lühendmõistatused, ed. by Piret Voolaid, http://www.folklore.ee/Lyhendid/. Database of Estonian abbreviation-based puzzles, of the type 'Mida tähendas ETA? – Eeslid tulevad appi' ('What does ETA mean? – Donkeys come to the rescue').

- Eesti värssmõistatused, ed. by Piret Voolaid, http://www.folklore.ee/Varssmoistatused/. Database of over 3,000 verse riddles.

- Eesti liitsõnamängud, ed. by Piret Voolaid, http://www.folklore.ee/Sonamang/. Database of nearly 5,000 compound word puzzles, of the type 'Missugune suu ei räägi? – Kotisuu (‘Which mouth cannot speak? – A bag’s mouth.’)

Finnish riddles have received some, but not very extensive study.[25]

See also

References

- Leea Virtanen, 'The Collecting and Study of Riddles in Finland', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 51-57.

- Finnish Folk Poetry: Epic. An Anthology in Finnish and English, ed. and trans. by Matti Kuusi, Keith Bosley and Michael Branch, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia, 329 (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 1977), pp. 33-34.

- Leea Virtanen, 'The Collecting and Study of Riddles in Finland', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 51-57.

- Leea Virtanen, 'On the Function of Riddles', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 77-89 (at 80-82).

- Finnish Folk Poetry: Epic. An Anthology in Finnish and English, ed. and trans. by Matti Kuusi, Keith Bosley and Michael Branch, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia, 329 (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 1977), pp. 37-38.

- Piret Voolaid, ‘Constructing Digital Databases of the Periphery of Estonian Riddles. Database Estonian Droodles’, Folklore, 25 (2003), 87-92 (p. 87), doi:10.7592/FEJF2003.25.droodles.

- Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 143 (no. 378) and 116-17 (no. 181).

- Piret Voolaid, ‘Constructing Digital Databases of the Periphery of Estonian Riddles. Database Estonian Droodles’, Folklore, 25 (2003), 87-92 (p. 87), doi:10.7592/FEJF2003.25.droodles.

- Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, 'Means of Riddle Expression', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 58-76 (p. 65).

- Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, The Nominativus Absolutus Formula: One Syntactic-Semantic Structural Scheme of the Finnish Riddle Genre [trans. by Susan Sinisalo], FF Communications, 222 (Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1978).

- Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, 'Means of Riddle Expression', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 58-76 (p. 65; cf. pp. 141-42 [no. 371 A3a]).

- Matti Kuusi, 'Arvoitukset ja muinaisusko', Virittäjä: Kotikielen seuran aikakauslehti, 60 (1956), 181-201; Matti Kuusi, 'Seven Riddles', in Matti Kuusi, Mind and Form in Folklore: Selected Articles, ed. by Henni Ilomäki, trans. by Hildi Hawkins, Studia fennica. Folkloristica, 3 (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, [1994]), pp. 167-82.

- Leea Virtanen, 'On the Function of Riddles', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 77-89 (at 82, referring to how banishment to Hyvölä in the riddle-game uses charm-like verse).

- Matti Kuusi, 'Concerning Unwritten Literature', in Matti Kuusi, Mind and Form in Folklore: Selected Articles, ed. by Henni Ilomäki, trans. by Hildi Hawkins, Studia fennica. Folkloristica, 3 (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, [1994]), pp. 23-36 (p. 26). Quoted from Æschillus Petræus, Linguæ finnicæ brevis institutio, exhibens vocum flectiones per casus, gradus & tempora, nec non partium indeclinabilium significationem, dictionumq; constructionem & prosodiam. Ad usum accommodata (Åbo: Wald, 1649), p. 69, http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fd2015-00009344.

- Matti Kuusi, 'Concerning Unwritten Literature', in Matti Kuusi, Mind and Form in Folklore: Selected Articles, ed. by Henni Ilomäki, trans. by Hildi Hawkins, Studia fennica. Folkloristica, 3 (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, [1994]), pp. 23-36 (p. 25), [first publ. 1963].

- Leea Virtanen, 'On the Function of Riddles', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 77-89 (at 77-80).

- Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, 'Means of Riddle Expression', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 58-76 (p. 72-74).

- Leea Virtanen, 'On the Function of Riddles', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 77-89 (at 80-82).

- Leea Virtanen, 'On the Function of Riddles', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 77-89 (at 86-89).

- Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), p. 125 (nos. 248, 253).

- Matti Kuusi, 'Seven Riddles', in Matti Kuusi, Mind and Form in Folklore: Selected Articles, ed. by Henni Ilomäki, trans. by Hildi Hawkins, Studia fennica. Folkloristica, 3 (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, [1994]), pp. 167-82 (171-73, quoting 171).

- Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, Riddles: Perspectives on the Use, Function and Change in a Folklore Genre, Studia Fennica Folkloristica, 10 (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2016), p. 28.

- Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, Riddles: Perspectives on the Use, Function and Change in a Folklore Genre, Studia Fennica Folkloristica, 10 (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2016), p. 28.

- Leea Virtanen and Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, 'Editorial Principles', in Arvoitukset: Finnish Riddles, ed. by Leea Virtanen, Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj and Aarre Nyman, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Toimituksia, 329 ([Helsinki]: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1977), pp. 46-50 (at 46).

- Martti Haavio, 'Das Problem und seine Lösung', Studia Fennica, 8 (1959), 143-66; Elli Köngäs Maranda, 'Riddles and Riddling: An Introduction', The Journal of American Folklore, 89 (1976), 127-37; DOI: 10.2307/539686; https://www.jstor.org/stable/539686; Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, Riddles: Perspectives on the Use, Function, and Change in a Folklore Genre, Studia Fennica, Folkloristica, 10 (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2001), https://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sff.10.