Rhytidectomy

A facelift, technically known as a rhytidectomy (from Ancient Greek ῥυτίς (rhytis) "wrinkle" + ἐκτομή (ektome) "excision", surgical removal of wrinkles), is a type of cosmetic surgery procedure used to give a more youthful facial appearance.[1] There are multiple surgical techniques and exercise routines. Surgery usually involves the removal of excess facial skin, with or without the tightening of underlying tissues, and the redraping of the skin on the patient's face and neck. Exercise routines tone underlying facial muscles without surgery. Surgical facelifts are effectively combined with eyelid surgery (blepharoplasty) and other facial procedures and are typically performed under general anesthesia or deep twilight sleep.

| Rhytidectomy | |

|---|---|

_upper_incision.png) Temporal incision behind the hairline in endoscopic midface lift (rhytidectomy). Note the shiny surface of the deep temporal fascia. This plane is dissected down to the orbital rim and connected to the midface subperiosteal plane created through the sublabial incision under the upper lip, and often through a lower eyelid incision. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 86.82 |

| MedlinePlus | 002989 |

According to the most recent 2011 statistics from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, facelifts were the sixth most popular aesthetic surgery performed after liposuction, breast augmentation, abdominoplasty (tummy tuck), blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery) and breast lift.

History

_lower_incision.png)

Cutaneous period (1900–1970)

In the first 70 years of the 20th century facelifts were performed by pulling on the skin on the face and cutting the loose parts off. The first facelift was reportedly performed by Eugen Holländer in 1901 in Berlin.[2] An elderly Polish female aristocrat asked him to: "lift her cheeks and corners of the mouth". After much debate he finally proceeded to excise an elliptical piece of skin around the ears. The first textbook about facial cosmetic surgery (1907) was written by Charles Miller (Chicago) entitled The Correction of Featural Imperfections.[3]

In the First World War (1914–1918) the Dutch surgeon Johannes Esser made one of the most famous discoveries in the field of plastic surgery to date, namely the "skin graft inlay technique,"[4] the technique was soon used on both English and German sides in the war. At the same time the British plastic surgeon Harold Delfs Gillies used the Esser-graft to school all those who flocked towards him who wanted to study under him. That’s how he earned the name "Father of 20th Century Plastic Surgery". In 1919 Dr. Passot was known to publish one of the first papers on face-lifting, this consisted mainly on the elevating and redraping of the facial skin. After this many others began to write papers on face-lifting in the 1920s. From then the esthetic surgery was being performed on a large scale, from the basis of the reconstructive surgery. The first female plastic surgeon, Suzanne Noël, played a large role in its development and she wrote one of the first books about esthetic surgery named Chirurgie Esthetique, son rôle social.

SMAS period (1970–1980)

In 1968 Tord Skoog introduced the concept of subfacial dissection, therefore providing suspension of the stronger deeper layer rather than relying on skin tension to achieve his facelift (he publishes his technique in 1974, with subfacial dissection of the platysma without detaching the skin in a posterior direction).[5] In 1976 Mitz and Peyronie described the anatomical Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System, or SMAS,[6] a term coined by Paul Tessier, Mitz and Peyronie’s tutor in craniofacial surgery, after he had become familiar with Skoog’s technique. After Skoog died of a heart attack, the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS) concept rapidly emerged to become the standard face-lifting technique, which was the first innovative change in facelift surgery in over 50 years.[7]

Deep plane period (1980–1991)

Tessier, who had his background in the craniofacial surgery, made the step to a subperiosteal dissection via a coronal incision.[8] In 1979, Tessier demonstrated that the subperiosteal undermining of the superior and lateral orbital rims allowed the elevation of the soft tissue and eyebrows with better results than the classic face-lifting. The objective was to elevate the soft tissue over the underlying skeleton to re-establish the patient's youthful appearance.

Volumetric period (1991–today)

At the start of this period in the history of the facelift there was a change in conceptual thinking, surgeons started to care more about minimizing scars, restoring the subcutaneous volume that was lost during the ageing process and they started making use of a cranial direction of the "lift" instead of posterior.

The technique for performing a facelift went from simply pulling on the skin and sewing it back to aggressive SMAS and deep plane surgeries to a more refined facelift where variable options are considered to have an aesthetically good and a more long-lasting effect.

Indications

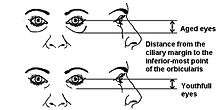

A facelift is performed to rejuvenate the appearance of the face. Aging of the face is most shown by a change in position of the deep anatomical structures, notably the platysma muscle, cheek fat and the orbicularis oculi muscle.[9] These lead up to three landmarks namely, an appearance of the jowl (a broken jaw line by ptosis of the platysma muscle), increased redundancy of the nasolabial fold (caused by a descent of cheek fat) and the increased distance from the ciliary margin to the inferior-most point of the orbicularis oculi muscle (caused by decreasing tone of the orbicularis oculi muscle).[9] The skin is a fourth component in the aging of the face. The ideal age for face-lifting is at age 50 or younger, as measured by patient satisfaction.[10][11][12] Some areas, such as the nasolabial folds or marionette lines, in some cases can be treated more suitably with Botox or liposculpture.

Contraindications

Contraindications to facelift surgery include severe concomitant medical problems, both physical and psychological. While not absolute contraindications, the risk of postoperative complications is increased in cigarette smokers and patients with hypertension and diabetes.[13] These strong relative contraindications consist primarily of diseases predisposing to poor wound healing. Patients are typically asked to abstain from taking aspirin or other blood thinners for at least one week prior to surgery. Patients motivations and expectations are an important factor in order to determine the patient’s medical status. A psychiatric illness leading to unreasonable expectations for the surgical outcome, such as a distorted perception of reality, can be a contraindication to surgery. Some kinds of hypersensitivity to anesthesia are a contraindication.

Surgical anatomy

| Facelift: Generally relevant anatomy | |

|---|---|

Head nerves | |

Head arteries | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Facial artery, Temporal artery, Arteria supratrochlearis, Arteria infraorbitalis |

| Vein | Temporal vein |

| Nerve | Greater auricular nerve, Facial nerve, Mental nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D015361 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

- A dissection in the deep plane can mostly be performed safely, because the facial nerve innervates the facial muscles on the deep surface of these muscles (except for the muscles which are lying deep to the facial nerve, the mentalis, the levator anguli oris and the buccinator). The fibres of the nerve are becoming more superficially medially. Therefore, the dissection of a deep plane begins further away of the surface then it ends. This allows the undermining to be carried out towards the nasolabial fold without harming the branches of the facial nerve.

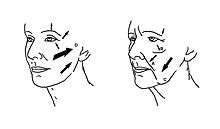

- Retaining ligaments

- The retaining ligaments in the face provide an anchorage of superficial structures to underlying bone. Four retaining ligaments exist.[14] The platysma-cutaneous ligaments and the platysma-auricular ligament are aponeurotic condensations which connect the platysma to the dermis. The osteocutaneous ligaments, the zygomatic ligament and the mandibular ligament, are more important. They attach to the skin and bone, leading to a counteraction of gravitational forces. These ligaments should be released surgically to obtain a fully mobile facelift flap.

- Nasolabial folds

- Melolabial folds (marionette lines)

- Greater auricular nerve

- Injury to the greater auricular nerve is the most seen nerve injury after rhytidectomy.[15][16] Care should be taken in elevation over the sternocleidomastoid muscle, because of the terminal branches of the nerve that pass superficially to innervate the earlobe.

- The composite flap is vascularised by facial, angular and/or inferior orbital arteries. The facial artery supplies the platysma and goes on as the angular artery, which connects with the branches of the arteria supratrochlearis and arteria infraorbitalis. The parts of the face elevated are in continuity in the deep-plane and the composite rhytidectomy include the SMAS layer in the lower face, subcutaneous tissue and the skin as the arteries to these parts are preserved.[17] With this option you can create a well vascularized tissue flap, which can be used to tighten the skin without loss of vascularization, this will result in fewer complications like skin slough and necrosis.

Procedure

Many different procedures of rhytidectomy exist.[18] The differences are mostly the type of incision, the invasiveness and the area of the face that is treated. Each surgeon practices multiple different types of facelift surgery. At a consultation the procedure with the best outcome is chosen for every patient. Expectations of the patient, the age, possible recovery time and areas to improve are some of the many factors taken in consideration before choosing a technique of rhytidectomy.

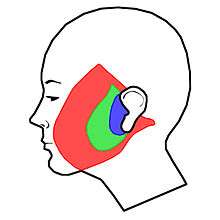

In the traditional facelift, an incision is made in front of the ear extending up into the hairline. The incision curves around the bottom of the ear and then behind it, usually ending near the hairline on the back of the neck. After the skin incision is made, the skin is separated from the deeper tissues with a scalpel or scissors (also called undermining) over the cheeks and neck. At this point, the deeper tissues (SMAS, the fascial suspension system of the face) can be tightened with sutures, with or without removing some of the excess deeper tissues. The skin is then redraped, and the amount of excess skin to be removed is determined by the surgeon's judgement and experience. The excess skin is then removed, and the skin incisions are closed with sutures and staples.

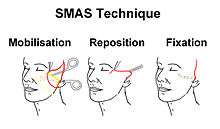

SMAS lift

The SMAS (Superficial Musculo Aponeurotic System) layer consists of suspensory ligaments that encase the cheek fat, thereby causing them to remain in their normal position. Resuspension and securing the SMAS anatomical layer can lead to rejuvenation of the face, by counteracting aging and gravity caused laxity. Modifications to this technique led to development of the "Composite Facelift" and "Deep plane Facelift."

Deep-plane facelift

In order to correct the deepening of the nasolabial fold more accurately, the deep plane facelift was developed. Differing from the SMAS lift by freeing cheek fat and some muscles from their bone implement. This technique has a higher risk at damaging the facial nerve. The SMAS lift is an effective procedure to reposition the platysma muscle; however, the nasolabial fold is according to some surgeons better addressed by a deep plane facelift or composite facelift.

Composite facelift

As well as in the deep plane facelift, in the composite facelift a deeper layer of tissue is mobilised and repositioned. The difference between these operating techniques is the extra repositioning and fixation of the orbicularis oculi muscle in the composite facelift procedure. The malar crescent caused by the orbicularis oculi ptosis can be addressed in a composite facelift.

Mid face-lift

The mid face area, the area between the cheeks, flattens and makes a woman’s face look slightly more masculine. The mid face-lift is suggested to people where these changes occur, yet without a significant degree of jowling or sagging of the neck. In these cases a mid face-lift is sufficient to rejuvenate the face opposed to a full facelift, which is a more drastic surgery. The ideal candidates for a mid face-lift is when a person is in his 40s, or if the cheeks appear to be sagging and the nasolabial area has laxity or skin folds. To achieve a younger appearance the surgeon makes several small incisions along the hairline and inside the mouth, this way the fatty tissue layers can be lifted and repositioned. This way there are practically no scars. The fatty layer that lies over the cheekbones is also lifted and repositioned. This improves the nose-to-mouth lines and the roundness over the cheekbones. The recovery time is rather short and this procedure is often combined with a blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery)

Mini-facelift

The mini-facelift is the least invasive type of facelift which is similar to a full facelift, the only difference is the omission of the neck lift in the mini lift procedure. It is also called the ‘S’ lift because of the shape of the incision that is used or the ‘short-scar’ facelift. This lift is a more temporary solution to the ageing of the face which also has less downtime and is done on people who have deep nasolabial folds, sagging facial structures, yet still have a firm and well-contoured neck. The position of the incision is usually made from the hairline around the ear with scars hidden in the natural crease of the skin. The mini lift can be performed with an endoscope, which is used to reposition the soft tissues. After this, the skin is repositioned by the surgeon with small sutures. This type of lift is a good alternative to the full facelift to people with premature ageing.

Subperiosteal facelift

The subperiosteal facelift technique is done by vertically lifting the soft tissues of the face, completely separating it from the underlying facial bones and elevating it to a more esthetically pleasing position, correcting deep nasolabial folds and sagging cheeks. The technique is often combined with standard techniques, which provide a long-lasting rejuvenation of the face and is done in all age groups. The difference between this and other lifts is that the subperiosteal facelift has a longer period of facial swelling after the procedure.

Skin-only facelift

With the skin-only facelift only the skin of the face is lifted and not the underlying SMAS, muscles or other structures. As the elastin fibers disintegrate, the skin itself loses elasticity in older patiënts. A skin only face lift requires skill in understanding the extent of safe removal of skin and the Vector of pull to get an optimal result. It can be done with a simple ellipse of skin removed with minimal undermining of skin flaps or more extensively with large skin flaps. It can last 5 to 10 years but some patients may want a touch-up at 6 to 12 months after the procedure. The reason that this option is considered is that it has fewer complications and quicker recovery. One of the father's of plastic surgery Sir Harold Gilles described a simple ellipse of skin excision in a socialite who was pleased with her quick recovery and outcome. Can be done for a simple jowl lift in a 35 to 45 year old patient.

MACS facelift

The term MACS-lift – or Minimal Access Cranial Suspension lift – allows for the correction of sagging facial features through a short, minimal incision, elevating them vertically by suspending them from above. There are many advantages to having a MACS facelift versus a traditional facelift. For starters, the MACS-lift uses a shorter scar that is in front of the ear, instead of behind, which is much easier to hide. Overall, the MACS-lift surgery is safer because less skin is raised. This means that there is less risk of bleeding and nerve damage. The operation also takes less time, lasting 2.5 hours instead of the 3.5 hours that the traditional facelift requires. There is also a shorter recovery period, 2–3 weeks instead of 3–4 weeks. Finally, the results of the MACS-lift are very natural while the traditional facelift will often result in a "windswept" look. The MACS lift has been successfully used for to correct complication after thread-lift with APTOS[19]

Complications

The most common complication is bleeding which usually requires a return to the operating room. Less common, but potentially serious, complications may include damage to the facial nerves and necrosis of the skin flaps or infection. Although the facial plastic surgeon attempts to prevent and minimise the risk of complications, a rhytidectomy can have complications. As a risk to every operation, complications can be derived as a reaction to the anesthetics.

Hematoma is the most seen complication after rhytidectomy.[15][16][20][21][22][23][24] Arterial bleeding can cause the most dangerous hematomas, as they can lead to dyspnea. Almost all of the hematomas occur within the first 24 hours after the rhytidectomy.[15][16][20]

Nerve injury can be sustained during rhytidectomy. This kind of injury can be temporary or permanent and harm can be done to either sensory or motor nerves of the face. As an sensory nerve, the great auricular nerve is the most common nerve to get injured at a facelift procedure.[16][20] The most injured motor nerve is the facial nerve.[16][25]

Skin necrosis can occur after a facelift operation. Smoking increases the risk of skin necrosis 12-fold.[13] Scarring is considered a complication of facelift surgery. Hypertrophic scars can appear. A facelift requires skin incisions; however, the incisions in front of and behind the ear are usually inconspicuous.

Hair loss in the portions of the incision within the hair-bearing scalp can rarely occur. A hairline distortion can result after undergoing a rhytidectomy. Especially facial hair by men after a facelift procedure. There is a high incidence of alopecia after rhytidectomy.[26][27] The permanent hair loss is mostly seen at the incision site in the temporal areas. In men, the sideburns can be pulled backwards and upwards, resulting in an unnatural appearance if appropriate techniques are not employed to address this issue. Achieving a natural appearance following surgery in men can be more challenging due to their hair-bearing preauricular skin. In both men and women, one of the signs of having had a facelift can be an earlobe which is pulled forwards and/or distorted. If too much skin is removed, or a more vertical vector not employed, the face can assume a pulled-back, "windswept" appearance. This appearance can also be due to changes in bone structure that generally happen with age.[2]

One of the most often overlooked (or not discussed) areas of a traditional facelift procedure is the effects on the anatomical positioning and angles of the ears. Most patients are, in many cases, not made aware that the vector forces in a facelift will lower the ears as well as change the angle of the ears. Ear lowering can be as much as 1 cm and change in the angle as much as 10 degrees.

Infection is a rare complication for patients who have undergone a rhytidectomy.[28] Staphylococcus is the most usual causative organism for an infection after facelift surgery.[15]

Society

Cost varies by country where surgery is performed, as of 2008:[29]

- Canada – US$7,000–15,000

- Pakistan – US$5,500

- Malaysia – US$6,400

- Panama – US$2,500

- Russia – US$10,000

- Singapore – US$7,500

- South Korea – US$6,650

- India – US$2500

- Taiwan – US$8,500

- Thailand – US$5,000

- United States – US$7,000–$15,000

Additional Notes on Costs in Europe, as of 2009:[30]

- Belgium – GBP £1,650 and up

- Italy – GBP £5,000

- United Kingdom – £4,000–£9,000

- Serbia – GBP £4000

See also

- Cosmetic surgery

- Facial toning

- Micro-current treatment ("non-surgical" facelift)

- Lifestyle lift

- Minimal access cranial suspension

- Oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Otolaryngology

- Plastic surgery

- Superficial muscular aponeurotic system

Footnotes

- "Defining Facelift". Hedox Clinic. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Panfilov, Dimitrije E. (2005). Cosmetic Surgery Today. Trans. Grahame Larkin. New York, N.Y.: Thiene. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-58890-334-1.

- Kita, Natalie. "The History of Plastic Surgery". Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- van Bergen, Leo. "Mens of monster? Plastische chirurgie en de Eerste Wereldoorlog".

- Skoog, Tord Gustav (1974). Plastic Surgery: New Methods and Refinements. Saunders. p. 500. ISBN 978-0721683553.

- Mitz, V.; Peyronie M. (July 1976). "The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area". Plast Reconstr Surg. 1. 58 (1): 80–8. doi:10.1097/00006534-197607000-00013. PMID 935283.

- Tessier, P. (September 1979). "Facelifting and frontal rhytidectomy". Transactions of 7th International Conference on Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

- Heinrichs, HL; Kaidi, AA (September 1998). "Subperiosteal face lift: a 200-case, 4-year review". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 102 (3): 843–55. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809030-00036. PMID 9727455.

- Hamra, S.T. (April 1997). "Composite Rhytidectomy". Plast Reconstr Surg. 24 (2): 1–13.

- Marcus, BC (August 2012). "Rhytidectomy: current concepts, controversies and the state of the art". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 20 (4): 262–6. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e328355b175. PMID 22894994.

- Friel, M; Shaw RE; Trovato MJ; Owsley JQ (July 2010). "The measure of face-lift patient satisfaction: the Owsley Facelift Satisfaction Survey with a long-term followup study". Plast Reconstr Surg. 126 (1): 245–57. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181dbc2f0. PMID 20224460.

- Liu, TS; Owsley, JQ (January 2012). "Long-term results of face lift surgery: patient photographs compared with patient satisfaction ratings". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 129 (1): 253–62. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182362b55. PMID 22186515.

- Rees, TD; Liverett, DM; Guy, CL (June 1984). "The effect of cigarette smoking on skin-flap survival in the face lift patient". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 73 (6): 911–5. doi:10.1097/00006534-198406000-00009. PMID 6728942.

- Furnas, DW (January 1989). "The retaining ligaments of the cheek". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 83 (1): 11–6. doi:10.1097/00006534-198901000-00003. PMID 2909050.

- Moyer, JS; Baker, SR (August 2005). "Complications of rhytidectomy". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 13 (3): 469–78. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2005.04.005. PMID 16085292.

- Baker, DC (July 1983). "Complications of cervicofacial rhytidectomy". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 10 (3): 543–62. PMID 6627843.

- Whetzel, TP; Mathes, SJ (August 1997). "The arterial supply of the face lift flap". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 100 (2): 480–6, discussion 487–8. doi:10.1097/00006534-199708000-00033. PMID 9252619.

- "Facelift (rhytidectomy) approach".

- "Successful treatment of thread-lifting complication from APTOS sutures using a simple MACS lift and fat grafting". Aesthetic Plast Surg. 36: 1307–10. December 2012. doi:10.1007/s00266-012-9975-1. PMID 23052379.

- Rees, TD; Aston, SJ (January 1978). "Complications of rhytidectomy". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 5 (1): 109–19. PMID 639438.

- Cohen, SR; Webster, RC (May 1983). ""How I do it"—head and neck and plastic surgery. A targeted problem and its solution. Primary rhytidectomy—complications of the procedure and anesthetic". The Laryngoscope. 93 (5): 654–6. doi:10.1002/lary.1983.93.5.654. PMID 6843261.

- Clevens, RA (November 2009). "Avoiding patient dissatisfaction and complications in facelift surgery". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 17 (4): 515–30, v. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2009.06.005. PMID 19900658.

- Kamer, FM; Song, AU (October–December 2000). "Hematoma formation in deep plane rhytidectomy". Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2 (4): 240–2. doi:10.1001/archfaci.2.4.240. PMID 11074716.

- Niamtu J, 3rd (September 2005). "Expanding hematoma in face-lift surgery: literature review, case presentations, and caveats". Dermatologic Surgery. 31 (9 Pt 1): 1134–44, discussion 1144. doi:10.1097/00042728-200509000-00012. PMID 16164866.

- Baker, DC; Conley, J (December 1979). "Avoiding facial nerve injuries in rhytidectomy. Anatomical variations and pitfalls". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 64 (6): 781–95. doi:10.1097/00006534-197912000-00005. PMID 515227.

- Leist, FD; Masson, JK; Erich, JB (April 1977). "A review of 324 rhytidectomies, emphasizing complications and patient dissatisfaction". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 59 (4): 525–9. doi:10.1097/00006534-197759040-00008. PMID 847029.

- Baker, TJ; Gordon, HL; Mosienko, P (January 1977). "Rhytidectomy: a statistical analysis". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 59 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1097/00006534-197701000-00004. PMID 831238.

- LeRoy JL, Rees TD, Nolan WB (March 1994). "Infections requiring hospital readmission following face lift surgery: incidence, treatment, and sequelae". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 93 (3): 533–6. doi:10.1097/00006534-199493030-00013. PMID 8115508.

- Comarow, Avery (12 May 2008). Under the Knife in Bangalore. US News and World Report.

- "Face Lift Fact Sheet". BuyAssociation. 2009.