Gastric-brooding frog

The gastric-brooding frogs or platypus frogs (Rheobatrachus) is a genus of extinct ground-dwelling frogs native to Queensland in eastern Australia. The genus consisted of only two species, both of which became extinct in the mid-1980s. The genus is unique because it contains the only two known frog species that incubated the prejuvenile stages of their offspring in the stomach of the mother.[3]

| Gastric-brooding frogs | |

|---|---|

| |

| Southern gastric-brooding frog (Rheobatrachus silus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Myobatrachidae |

| Subfamily: | †Rheobatrachinae Heyer & Liem, 1976 |

| Genus: | †Rheobatrachus Liem, 1973 |

| |

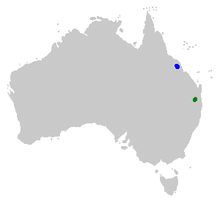

| The former distributions of Rheobatrachus silus (green) and Rheobatrachus vitellinus (blue) | |

The combined ranges of the gastric-brooding frogs comprised less than 2,000 square kilometres (770 sq mi). Both species were associated with creek systems in rainforests at elevations of between 350 and 1,400 metres (1,150 and 4,590 ft). The causes of the gastric-brooding frogs' extinction are not clearly understood, but habitat loss and degradation, pollution, and some diseases may have contributed.

The assignment of the genus to a taxonomic family is hotly debated. Some biologists class them within Myobatrachidae under the subfamily Rheobatrachinae, but others place them in their own family, Rheobatrachidae.[4]

Scientists at the University of Newcastle and University of New South Wales announced in March 2013 that the frog would be the subject of a cloning attempt, referred to as the ”Lazarus Project”, to resurrect the species. Embryos were successfully cloned, and the project eventually hopes to produce a living frog.[5][6]

The southern gastric brooding frog has been listed as Extinct by the IUCN because it has not been recorded in the wild since 1981, and extensive searches over the last 35 years have failed to locate this species.

Taxonomy

The genus Rheobatrachus was first described in 1973 by David Liem[7] and since has not undergone any scientific classification changes; however its placement has been controversial. It has been placed in a distinct subfamily of Myobatrachidae, Rheobatrachinae; in a separate family, Rheobatrachidae; placed as the sister taxon of Limnodynastinae; and synonymized with Limnodynastinae. In 2006, D. R. Frost and colleagues found Rheobatrachus, on the basis of molecular evidence, to be the sister taxon of Mixophyes and placed it within Myobatrachidae.[8][9]

Both species of gastric-brooding frogs were very different in appearance and behaviour from other Australian frog species. Their large protruding eyes and short, blunt snout along with complete webbing and slimy bodies differentiated them from all other Australian frogs. The largely aquatic behaviour exhibited by both species was only shared (in Australia) with the Dahl's Aquatic Frog and their ability to raise their young in the mother's stomach was unique among all frogs.

Common names

The common names, "gastric-brooding frog" and "platypus frog", are used to describe the two species. "Gastric-brooding" describes the unique way the female raised the young and "platypus" describes their largely aquatic nature.

Southern gastric-brooding frog (R. silus)

Distribution

The southern gastric-brooding frog (Rheobatrachus silus) was discovered in 1972 and described in 1973,[7] though there is one publication suggesting that the species was discovered in 1914 (from the Blackall Range).[10] Rheobatrachus silus was restricted to the Blackall Range and Conondale Ranges in southeast Queensland, north of Brisbane, between elevations of 350 and 800 metres (1,150 and 2,620 ft) above sea level.[11] The areas of rainforest, wet sclerophyll forest and riverine gallery open forest that it inhabited were limited to less than 1,400 km2 (540 sq mi). They were recorded in streams in the catchments of the Mary, Stanley and Mooloolah Rivers.[12] Depending on the source, the last specimen seen in the wild was in 1979 in the Conondale Range, or in 1981 in the Blackall Ranges. The last captive specimen died in 1983. This species is believed to be extinct.

Description

The southern gastric-brooding frog was a medium-sized species of dull colouration, with large protruding eyes positioned close together and a short, blunt snout. Its skin was moist and coated with mucus. The fingers were long, slender, pointed and unwebbed and the toes were fully webbed. The arms and legs were large in comparison to the body. In both species the females were larger than the males.

The southern gastric-brooding frog was a dull grey to slate coloured frog that had small patches, both darker and lighter than the background colouration, scattered over dorsal surface (back). The ventral surface was white or cream, occasionally with yellow blotches. The arms and legs had darker brown barring above and were yellow underneath. There was a dark stripe that ran from the eye to the base of the forelimb. The ventral surface (belly) was white with large patches of cream or pale yellow. The toes and fingers were light brown with pale brown flecking. The end of each digit had a small disc and the iris was dark brown. The skin was finely granular and the tympanum was hidden. The male Southern Gastric Brooding Frog was 33 to 41 millimetres (1.3 to 1.6 in) in length and the female 44 to 54 millimetres (1.7 to 2.1 in) in length.

Ecology and behaviour

The southern gastric-brooding frog lived in areas of rainforest, wet sclerophyll forest and riverine gallery open forest. They were a predominately aquatic species closely associated with watercourses and adjacent rock pools and soaks. Streams that the southern gastric-brooding frog were found in were mostly permanent and only ceased to flow during years of very low rainfall.[13] Sites where southern gastric-brooding frogs were found usually consisted of closed forests with emergent eucalypts, however there was sites where open forest and grassy ground cover were the predominate vegetation. There is no record for this species occurring in cleared riparian habitat. Searches during spring and summer showed that the favored diurnal habitat was at the edge of rock pools, either amongst leaf litter, under or between stones or in rock crevices. They were also found under rocks in shallow water. Winter surveys of sites where southern gastric-brooding frogs were common only recovered two specimens, and it is assumed that they hibernated during the colder months. Adult males preferred deeper pools than the juveniles and females which tended to inhabit shallower, newly created (after rain) pools that contained stones and/or leaf litter. Individuals only left themselves fully exposed while sitting on rocks during light rain.[12]

The call of the southern gastric-brooding frog has been described as an "eeeehm...eeeehm" with an upward inflection. It lasts for around 0.5 s and was repeated every 6–7 seconds.

Southern gastric-brooding frogs have been observed feeding on insects from the land and water. In aquarium situations Lepidoptera, Diptera and Neuroptera were eaten.[7]

Being a largely aquatic species the southern gastric-brooding frog was never recorded more than 4 m (13 ft) from water. Studies by Glen Ingram showed that the movements of this species were very restricted. Of ten juvenile frogs, only two moved more than 3 metres between observations. Ingram also recorded the distance moved along a stream by seven adult frogs between seasons (periods of increased activity, usually during summer). Four females moved between 1.8–46 metres (5 ft 11 in–150 ft 11 in) and three males covered 0.9–53 m (2 ft 11 in–173 ft 11 in). Only three individuals moved more than 5.5 m (18 ft) (46 m, 46 m and 53 m). It appeared that throughout the breeding season adult frogs would remain in the same pools or cluster of pools, only moving out during periods of flooding or increased flow.[12]

Northern gastric-brooding frog (R. vitellinus)

Distribution

The northern gastric-brooding frog (Rheobatrachus vitellinus) was discovered in 1984 by Michael Mahony.[14] It was restricted to the rainforest areas of the Clarke Range in Eungella National Park and the adjacent Pelion State Forest in central eastern Queensland. This species, too, was confined to a small area – less than 500 km2 (190 sq mi),[15] at altitudes of 400–1,000 m (1,300–3,300 ft).[16] Only a year after its discovery, it was never seen again despite extensive efforts to locate it.[17] This species is considered to be extinct.

Description

The northern gastric-brooding frog was a much larger species than the southern gastric-brooding frog. Males reached 50–53 mm (2.0–2.1 in) in length, and females 66–79 mm (2.6–3.1 in) in length. This species was also much darker in colour, usually pale brown, and like the southern gastric-brooding frogs its skin was bumpy and had a slimy mucus coating. There were vivid yellow blotches on the abdomen and the underside of the arms and legs. The rest of the belly was white or grey in colour. The tympanum was hidden and the iris was dark brown. The body shape of the northern gastric-brooding frog was very similar to the southern species.

Ecology and behaviour

The northern gastric-brooding frog was only recorded in pristine rainforests where the only form of human disturbance was poorly defined walking tracks. As with the southern gastric-brooding frog, the northern gastric-brooding frog was also a largely aquatic species. They were found in and around the shallow sections of fast flowing creeks and streams where individuals were located in shallow, rocky, broken-water areas, in cascades, riffles and trickles.[15] The water in these streams was cool and clear, and the frogs hid away beneath or between boulders in the current or in backwaters.

Male northern gastric-brooding frogs called from the water's edge during summer. The call was loud, consisting of several staccato notes. It was similar to the southern gastric-brooding frog's call although deeper, shorter and repeated less often.

The northern gastric-brooding frog was observed feeding on small crayfish, caddisfly larvae and terrestrial and aquatic beetles as well as the Eungella torrent frog (Taudactylus eungellensis).[18]

Reproduction

What makes these frogs unique among all frog species is their form of parental care. Following external fertilization by the male, the female would take the eggs or embryos into her mouth and swallow them.[19] It is not clear whether the eggs were laid on the land or in the water, as it was never observed before their extinction.

Eggs found in females measured up to 5.1 mm in diameter and had large yolk supplies. These large supplies are common among species that live entirely off yolk during their development. Most female frogs had around 40 ripe eggs, almost double that of the number of juveniles ever found in the stomach (21–26). This means one of two things, that the female fails to swallow all the eggs or the first few eggs to be swallowed are digested.

At the time the female swallowed the fertilized eggs her stomach was no different from that of any other frog species. In the jelly around each egg was a substance called prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which could turn off production of hydrochloric acid in the stomach. This source of PGE2 was enough to cease the production of acid during the embryonic stages of the developing eggs. When the eggs had hatched the tadpoles created PGE2. The mucus excreted from the tadpoles' gills contained the PGE2 necessary to keep the stomach in a non-functional state. These mucus excretions do not occur in tadpoles of most other species. Tadpoles that don't live entirely off a yolk supply still produce mucus cord, but the mucus along with small food particles travels down the oesophagus into the gut. With Rheobatrachus (and several other species) there is no opening to the gut and the mucus cords are excreted. During the period that the offspring were present in the stomach the frog would not eat.

Information on tadpole development was observed from a group that was regurgitated by the mother and successfully raised in shallow water. During the early stages of development tadpoles lacked pigmentation, but as they aged they progressively develop adult colouration. Tadpole development took at least six weeks, during which time the size of the mother's stomach continued to increase until it largely filled the body cavity. The lungs deflated and breathing relied more upon gas exchange through the skin. Despite the mother's increasing size she still remained active.

The birth process was widely spaced and may have occurred over a period of as long as a week. However, if disturbed the female may regurgitate all the young frogs in a single act of propulsive vomiting. The offspring were completely developed when expelled and there was little variation in colour and length of a single clutch.[20]

Cause of extinction

The cause for the gastric-brooding frogs' extinction is speculated to be due to human introduction of pathogenic fungi into their native range. Populations of southern gastric-brooding frogs were present in logged catchments between 1972 and 1979. The effects of such logging activities upon southern gastric-brooding frogs was not investigated but the species did continue to inhabit streams in the logged catchments. The habitat that the southern gastric-brooding frog once inhabited is now threatened by feral pigs, the invasion of weeds, altered flow and water quality problems caused by upstream disturbances.[11] Despite intensive searching, the species has not been located since 1979 or 1981 (depending on the source).

The Eungella National Park, where the northern gastric-brooding frog was once found, was under threat from bushfires and weed invasion. Continual fires may have destroyed or fragmented sections of the forest.[18] The outskirts of the park are still subject to weed invasion and chytrid fungus has been located within several rainforest creeks within the park. It was thought that the declines of the northern gastric-brooding frog during 1984 and 1985 were possibly normal population fluctuations.[15] Eight months after the initial discovery of the northern gastric-brooding frog, sick and dead Eungella torrent frogs, which cohabitat the streams with gastric brooding frogs, were observed in streams in Pelion State Forest.[21] Given the more recent understanding of the role of the amphibian disease in the decline and disappearance of amphibians, combined with the temporal and spatial pattern of the spread of the pathogen in Australia, it appears most likely that the disease was responsible for the decline and disappearance of the gastric-brooding frogs. Despite continued efforts to locate the northern gastric-brooding frog it has not been found. The last reported wild specimen was seen in the 1980s. In August 2010 a search organised by the Amphibian Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature set out to look for various species of frogs thought to be extinct in the wild, including the gastric-brooding frog.[22]

Conservation status

Both species are listed as Extinct under both the IUCN Red List and under Australia's Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999; however, they are still listed as Endangered under Queensland's Nature Conservation Act 1992.

De-extinction attempt

Scientists are making progress in their efforts to bring the gastric-brooding frog species back to life using somatic-cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), a method of cloning.[23]

In March 2013, Australian scientists successfully created a living embryo from non-living preserved genetic material. These scientists from the University of Newcastle Australia led by Prof Michael Mahony, who was the scientist who first discovered the northern gastric-brooding frog, Simon Clulow and Prof Mike Archer from the University of New South Wales hope to continue using somatic-cell nuclear transfer methods to produce an embryo that can survive to the tadpole stage. "We do expect to get this guy hopping again," says UNSW researcher Mike Archer.[24]

The scientists from the University of Newcastle have also reported successful freezing and thawing (cryopreservation) of totipotent amphibian embryonic cells,[25] which along with sperm cryopreservation [26] provides the essential "proof of concept" for the use of cryostorage as a genome bank for threatened amphibians and also other animals.

References

- Meyer, Ed et al. (2004). Rheobatrachus silus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2

- Hero, Jean-Marc et al. (2004). Rheobatrachus vitellinus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2

- Barker, J.; Grigg, G. C.; Tyler, M. J. (1995). A Field Guide to Australian Frogs. Surrey Beatty & Sons. p. 350. ISBN 0-949324-61-2.

- Heyer, W. Ronald; Liem, David S. (1976). "Analysis of the inter-generic relationships of the Australian frog family Myobatrachidae" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 233 (233): 1–29. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.233.

- Yong, Ed (15 March 2013). "Resurrecting the Extinct Frog with a Stomach for a Womb". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Dolak, Kevin (20 March 2013). "Frog That Gives Birth Through Mouth to be Brought Back From Extinction". ABC News.

- Liem, David S. (1973). "A new genus of frog of the family Leptodactylidae from S. E. Queensland, Australia". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 16 (3): 459–470.

- Amphibian Species of the World – Rheobatrahus (under "Comments"). research.amnh.org

- Frost, Darrel R.; Grant, Taran; Faivovich, Julián; Bain, Raoul H.; Haas, Alexander; Haddad, Célio F.B.; De Sá, Rafael O.; Channing, Alan; Wilkinson, Mark; Donnellan, Stephen C.; Raxworthy, Christopher J.; Campbell, Jonathan A.; Blotto, Boris L.; Moler, Paul; Drewes, Robert C.; Nussbaum, Ronald A.; Lynch, John D.; Green, David M.; Wheeler, Ward C. (2006). "The amphibian tree of life". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 297: 1–370. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2006)297[0001:TATOL]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5781.

- Ingram, G. J. (1991). "The earliest records of the extinct platypus frog". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 30 (3): 454.

- Hines, H., Mahony, M. and McDonald, K. 1999. An assessment of frog declines in Wet Subtropical Australia. In: A. Campbell (ed.), Declines and Disappearances of Australian Frogs. Environment Australia.

- Ingram, G. J. (1983). "Natural History". In: M. J. Tyler (ed.), The Gastric Brooding Frog, pp. 16–35. Croom Helm, London.

- Meyer, E., Hines, H. and Hero, J.-M. (2001). "Southern Gastric-brooding Frog, Rheobatrachus silus". In: Wet Forest Frogs of South-east Queensland, pp. 34–35. Griffith University, Gold Coast.

- Mahony, Michael; Tyler, Davies (1984). "A new species of the genus Rheobatrachus (Anura: Leptodactylidae) from Queensland". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 108 (3): 155–162.

- McDonald, K.R. (1990). "Rheobatrachus Liem and Taudactylus Straughan & Lee (Anura: Leptodactylidae) in Eungella National Park, Queensland: distribution and decline". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 114 (4): 187–194.

- Covacevich, J.A.; McDonald, K. R. (1993). "Distribution and conservation of frogs and reptiles of Queensland rainforests". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 34 (1): 189–199.

- McDonald, Keith; Alford, Ross (1999). Campbell, Alastair (ed.). "A Review of Declining Frogs in Northern Queensland". Declines and Disappearances of Australian Frogs. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Winter, J.; McDonald, K. (1986). "Eungella, the land of cloud". Australian Natural History. 22 (1): 39–43.

- "Rheobatrachus vitellinus — Northern Gastric-brooding Frog, Eungella Gastric-brooding Frog". Department of the Environment, Canberra. 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Tyler, M. J. (1994). Chapter 12, "Gastric Brooding Frogs", pp. 135–140 in Australian Frogs A Natural History. Reed Books

- Mahony, Michael. "Report to Queensland National Park on status of stream frogs in Pelion State Forest". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Black, Richard (9 August 2010). "Global hunt begins for 'extinct' species of frogs". BBC. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- Nosowitz, Dan (15 March 2013) Scientists Resurrect Bonkers Extinct Frog That Gives Birth Through Its Mouth. popsci.com

- Messenger, Stephen (15 March 2013) Scientists successfully create living embryo of an extinct species. treehugger.com

- Moreira, Nei; Lawson, Bianca; Clulow, Simon; Mahony, Michael J.; Clulow, John (2013). "Towards gene banking amphibian maternal germ lines: short-term incubation, cryoprotectant tolerance and cryopreservation of embryonic cells of the frog, Limnodynastes peronii". PLoS ONE. 8 (4): e60760. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860760L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060760. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3618038. PMID 23577155.

- Browne, Robert; Mahony, Clulow (2002). "A comparison of sucrose, saline, and saline with egg-yolk diluents on the cryopreservation of cane toad (Bufo marinus) sperm". Cryobiology. 44 (251–157): 251–7. doi:10.1016/S0011-2240(02)00031-7. PMID 12237090.

Further reading

- Barker, J.; Grigg, G. C.; Tyler, M. J. (1995): A Field Guide to Australian Frogs. Surrey Beatty & Sons.

- Pough, F. H.; Andrews, R. M.; Cadle, J. E.; Crump, M.; Savitsky, A. H. & Wells, K. D. (2003): Herpetology (3rd ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

- Ryan, M. (ed.) (2003): Wildlife of Greater Brisbane. Queensland Museum, Brisbane.

- Ryan, M. & Burwell, C. (eds.) (2003): Wildlife of Tropical North Queensland. Queensland Museum, Brisbane.

- Tyler, M. J. (1984): There's a frog in my throat/stomach. William Collins Pty Ltd, Sydney. ISBN 0-00-217321-2

- Tyler, M. J. (1994): Australian Frogs – A Natural History. Reed Books.

- Zug, G. E.; Vitt, L. J. & Caldwell, J. P. (2001): Herpetology (2nd ed.). Academic Press, San Diego, California.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Rheobatrachus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rheobatrachus. |

- "Gastric-brooding frog" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Animal Diversity Web – Rheobatrachus silus (Accessed 2006/08/19)

- American Museum of Natural History – Rheobatrachus (Accessed 2006/08/19)