Gerard Reve

Gerard Kornelis van het Reve (14 December 1923 – 8 April 2006) was a Dutch writer. He started writing as Simon van het Reve and adopted the shorter Gerard Reve [ˈɣeːrɑrt ˈreːvə] in 1973.[1] Together with Willem Frederik Hermans and Harry Mulisch, he is considered one of the "Great Three" (De Grote Drie) of Dutch post-war literature. His 1981 novel De vierde man (The Fourth Man) was the basis for Paul Verhoeven's 1983 film.

Gerard Reve | |

|---|---|

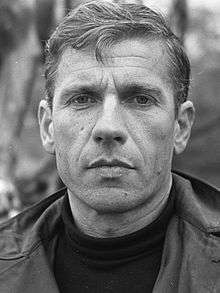

Gerard Reve in 1969 | |

| Born | Gerard Kornelis van het Reve 14 December 1923 Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Died | 8 April 2006 (aged 82) Zulte, East Flanders, Belgium |

| Resting place | Sint-Michiel-en-Cornelius-en-Ghislenuskerk, Machelen |

| Pen name | Simon van het Reve |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Language | Dutch |

| Residence | Greonterp Veenendaal Weert |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Alma mater | Vossius Gymnasium Grafische School |

| Genre | Novels, short stories, poems, letters, speeches |

| Notable awards | Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren |

| Years active | 1947–1998 |

| Spouse | Hanny Michaelis (m. 1948 – sep. 1959) |

| Partner | Joop Schafthuizen |

| Relatives | Karel van het Reve (brother) |

Reve was one of the first homosexual authors to come out in the Netherlands.[2] He often wrote explicitly about erotic attraction, sexual relations and intercourse between men, which many readers considered shocking. However, he did this in an ironic, humorous and recognizable way, which contributed to making homosexuality acceptable for many of his readers. Another main theme, often in combination with eroticism, was religion. Reve himself declared that the primary message in all of his work was salvation from the material world we live in.

Gerard Reve was born in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and was the brother of the Slavicist and essayist Karel van het Reve, who became a staunch anti-communist in his own way; the personal rapport between the brothers was not good. They broke off relations altogether in the 1980s.

Themes

.jpg)

He often insisted that homosexuality was merely a motif (providing idiom – as Roman Catholicism based phrases would differ from e.g. Buddhist wording – and, over time, idiosyncratic Reve-slang) in his work, the deeper theme being the inadequacy of human love (as opposed to divine love). Since the publication of Op weg naar het einde (Towards the end) (1963) and Nader tot U (Nearer to Thee) (1966), marking his breakthrough to a large audience, he articulated his views on God's creation and human fate, especially in the many collections of letters that he published.

These writings stress a symbolic, rather than ("...only the blind...") literal, understanding of religious texts as the only intellectually acceptable one, and the irrelevance of the Gospel's historical truth. Religion, according to Reve, has nothing to do with the literal, the factual, the moral or the political. It has no quarrel with modern science, because religious truths and empirical facts are in different realms. The observable world has no meaning beyond comparing facts, and, while revelation may not make sense, it has meaning, and it is this meaning that Reve was after in everything he wrote. Philosophically, Reve was influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer, whose works he re-read every winter, and even more so by Carl Jung, according to a Dutch painter who spent some time with the author in France to paint several portraits of him.[3]

Reve's erotic prose deals partly with his own sexuality, but aims at something more universal. Reve's work often depicts sexuality as ritual. Many scenes bear a sado-masochistic character, but this is never meant as an end in itself. 'Revism', a term coined by him, can roughly be described as consecrating sexual acts of punishment, dedicating these acts to revered others, and, ultimately, to higher entities (God). This is again a quest for higher significance in a human act (sex) that is devoid of meaning in its material form.

Style

His style combines the formal (in the kind of language one would find in a seventeenth-century Bible) with the colloquial, in a highly recognisable way. Similarly, his humour and often paradoxical view of the world relies on the contrast between exalted mysticism and common sense. The irony that pervades his work and his tendency towards extreme statements has caused confusion among readers. Many doubted the sincerity of his conversion to Catholicism, although Reve remained adamant about the truthfulness of his faith, claiming his right to individual notions about religion and his personal experience of it.

Controversies

Reve's literary career was marked by many controversies. Early on, the Dutch ministry of culture intervened when Reve was to receive a grant, citing the obscene nature of his work.

A member of the Dutch senate, the Calvinist senator Hendrik Algra, spoke on the same subject in a plenary debate. Reve sometimes welcomed the publicity, but also complained about his continual struggle with the authorities, public opinion and the press.

.jpg)

Reve was prosecuted in 1966 for allegedly breaking a law against blasphemy. In Nader tot U he describes the narrator's love-making to God, a visitor to his house incarnated in a one-year-old mouse-grey donkey. In April 1968 he was acquitted by the High Council. Although it would take decades for the Netherlands to decriminalize blasphemy, in 2013 the law was abolished, the outcome of this case — known as the “Donkey Trial” — rendered the existing law virtually obsolete [4]

Reve came from a communist and atheistic family, but converted to Roman Catholicism.[5] He was a very liberal Roman Catholic, and his ridiculing of some aspects of Catholicism led to tensions in the Dutch Roman Catholic community in the 1960s. Nevertheless, he contributed as a literary advisor to a new Catholic Bible translation, the 'Willibrord' translation.

One of Reve's main themes, along with religion and love, is his intense hatred of communism, its regimes and the tolerance toward it in leftist circles in the western world.

In 1975, he appeared at a Dutch poetry festival, wearing (among other things, a crucifix and peace symbol) a swastika as well as a hammer and sickle on his clothes, and read a poem that spoke of immigration in racist terms, though stressing cultural differences and using zwart (black) rather than neger/nikker (negro/nigger), in a solemn language that insulted many people, especially Afro-Surinamese, many of whom had arrived recently on the eve of the decolonization of Surinam that was to take place in November 1975.

This event led to much controversy, and many people have since wondered whether Reve had lost his mind, or had been alluding to something else. In the face of a wave of criticism Reve did not move an inch, and his claims of being 'too intelligent to be a racist' and never wanting to inflict any harm on any racial grounds partly got lost in the confusion generated by his ever-present irony.

In 2001, he was awarded the Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren, the most prestigious prize for Dutch-language authors, but King Albert II of Belgium refused to present it to him because his partner had been accused of pedophilia. The money was awarded by bank transfer and the certificate delivered.[1][6][7]

During the last years of his life, he began to suffer from Alzheimer's disease, and he died of it, in Zulte, Belgium, on 8 April 2006 at the age of 82. Reve was buried on April 15 in the centre of the cemetery "Nieuwe Begraafplaats" in Machelen-aan-de-Leie.

Honors

- 1947: Reina Prinsen Geerligs Award

- 2001: Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren[1]

Bibliography

- De Avonden (The evenings, 1947)

- Werther Nieland (1949)

- De ondergang van de familie Boslowits (The fall of the Boslowits family, 1950)

- Tien vrolijke verhalen (Ten happy stories, 1961)

- Vier Wintervertellingen (Four Winter Tales, 1963)

- Op weg naar het einde (Approaching the end, 1963)

- Nader tot U (Nearer to Thee, 1966)

- De taal der liefde (The language of love, 1972)

- Lieve jongens (Dear boys, 1973)

- Een circusjongen (A circus boy, 1975)

- Brieven aan kandidaat katholiek A. 1962–1969 (Letters to candidate Catholic A. 1962–1969, 1976)

- Oud en eenzaam (Old and lonely, 1978)

- Brieven aan Wimie (Letters to Wimie, 1980)

- Moeder en zoon (Mother and son, 1980)

- Brieven aan Bernard S. (Letters to Bernard S., 1981)

- De vierde man (The Fourth Man, 1981)

- Brieven aan Josine M. (Letters to Josine M., 1981)

- Brieven aan Simon C. 1971–1975 (Letters to Simon C. 1971–1975, 1982)

- Brieven aan Wim B. 1968–1975 (Letters to Wim B. 1968–1975, 1983)

- Brieven aan Frans P. 1965-1969 (Letters to Frans P. 1965-1969, 1984)

- De stille vriend (The silent friend, 1984)

- Brieven aan geschoolde arbeiders (Letters to educated workers, 1985)

- Zelf schrijver worden (Becoming a writer yourself, 1985)

- Brieven aan Ludo P. 1962-1980 (Letters to Ludo P. 1962-1980, 1986)

- Bezorgde ouders (Parents Worry, 1988)

- Brieven aan mijn lijfarts 1963–1980 (Letters to my personal physician 1963–1980, 1991)

- Brieven van een aardappeleter (Letters from a potato eater, 1993)

- Op zoek (Searching, 1995)

- Het boek van violet en dood (The book of violet and death, 1996)

- Ik bak ze bruiner (I bake them browner, 1996)

- Brieven aan Matroos Vosch (Letters to Matroos Vosch, 1997)

- Het hijgend hert (The panting deer, 1998)

Graphic novel

In 2003 and 2004 the novel De avonden (The evenings, 1947) was made into a graphic novel (in 4 parts) by Dick Matena.

In English

- The Acrobat (written in English, 1956). Amsterdam/ London, G.A. van Oorschot Publisher, 1956; 2nd ed. Amsterdam, Manteau, 1985.

- Parents Worry (Bezorgde ouders, 1990). Translated by Richard Huijing. London, Minerva, 1991

- The Evenings (De avonden, 1947). Translated by Sam Garrett. London, Pushkin Press, 2016

- Childhood. Two Novellas (Werther Nieland, 1949, and De ondergang van de familie Boslowits, 1950). Translated by Sam Garrett. London, Pushkin Press, 2018

Film adaptation

In 1980, Lieve jongens (Aka Dear Boys), directed by Paul de Lussanet, a comedy, drama starring Hugo Metsers, Hans Dagelet and Bill van Dijk. It explores gay desire, with an aging gay writer who becomes more demanding of the young men he has affairs with and their own relationship. It was based on several novels.[8]

See also

References

- Koopmans, Joop W.; Huussen, A. H., eds. (2007). "Reve, Gerard Kornelis van het (1923–2006)". Historical Dictionary of the Netherlands. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow. pp. 191–92.

- Wood, Robert (2002), "Reve, Gerard", glbtq.com, archived from the original on 11 October 2007, retrieved 24 October 2007

- Emoverkerk.nl

- Sex with God as a donkey: What constitutes blasphemy today? What's at stake when ancient ideas of heresy collide with the modern notion of free speech?

- Dutch and Flemish Literature Archived 1 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Osborn, Andrew (26 November 2001). "Dutch book prize kept from winner". The Guardian.

- "Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren na 11 jaar weer eens voor een Vlaming" (in Dutch). Boekendingen.nl. 26 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- David A. Gerstner (Editor) Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture , p. 421, at Google Books