Reserve Bank of Australia Building, Sydney

Reserve Bank of Australia Building is a heritage-listed bank building at 65 Martin Place, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It was added to the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List on 22 June 2004.[1]

| Reserve Bank of Australia building | |

|---|---|

Reserve Bank of Australia Building, Sydney, 2008 | |

| Location | 65 Martin Place, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33.8682°S 151.2117°E |

| Official name: Reserve Bank | |

| Type | Listed place (Historic) |

| Designated | 22 June 2004 |

| Reference no. | 105456 |

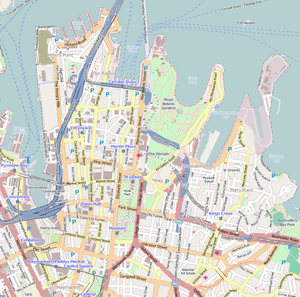

Location of Reserve Bank of Australia building in Sydney | |

History

Martin Place was originally a small lane called Moore Street which ran between George Street and Pitt Street and was widened into a substantial thoroughfare as part of the setting for the General Post Office in 1891. In 1921, Moore Street was renamed Martin Place. In 1926, the Municipal Council of Sydney purchased a number of properties in Macquarie and Phillip Streets in anticipation of the extension of Martin Place to Macquarie Street, including those properties which would later be demolished for the Reserve Bank of Australia's head office building. After Martin Place was formed the residential land on either side of the street was auctioned in 1936 however, the properties between Phillip and Macquarie Streets were passed in and did not sell until after World War II. The closure of Martin Place to traffic occurred between 1968 and 1978 and it became a pedestrianised civic plaza.[1]

History of the Reserve Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia was established by legislation in 1911. The main functions of the bank were to undertake general banking and savings bank activities. In 1945 the bank's powers were formally widened to include exchange control and the administration of monetary and banking policy with the Commonwealth Bank Act and the Banking Act. The Reserve Bank Act 1959 preserved the original corporate body under the name of the Reserve Bank of Australia to carry on the central banking functions of the Commonwealth Bank, but separated commercial banking and savings banking activities into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. The Reserve Bank has since then been Australia's central bank with its own Board, Governor and staff.[1]

The Reserve Bank has two broad responsibilities—monetary policy and the maintenance of financial stability, including the stability of the payments system. The Bank's powers are vested in the Reserve Bank Board and the Payments System Board. In carrying out its responsibilities, the Bank is an active participant in financial markets and the payments system. It is also responsible for the printing and issuing of Australian currency notes. As well as being a policy-making body, the Reserve Bank is a large financial institution which provides selected banking and registry services to Australian Government and state government customers and some overseas official institutions. Its assets include Australia's holdings of gold and foreign exchange. The Bank is wholly owned by the Australian Government.[1]

A requirement of the Reserve Bank Act 1959 was that the head office of the bank must not be in the same building as the head office of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) or any other bank. In line with this requirement, separate buildings were constructed for the state capitals Darwin and Canberra. The Bank currently consists of a Head Office, located in Sydney, branches in Adelaide and Canberra, regional offices in Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth and representative offices in London and New York.[1]

Reserve Bank site

The land on which the Reserve Bank is built, was in the 19th century occupied on by the first Wesleyan Chapel built in 1821 and subsequently used as a Unitarian Chapel in 1850, a Wesleyan School House also built in 1821 and purchased in 1843 by the Roman Catholic Church to be used as a school (demolished c. 1876). There was also a freestanding Georgian house occupied by a solicitor and a Georgian cottage.[1]

By the mid-1870s following the demolition of the church and school a row of three three-storey Italianate terrace houses known as "Lucretia Terrace" was erected (c. 1876). The Georgian house was demolished and two four-storey late Victorian terrace houses were erected (1891). In c. 1875 the Georgian cottage was demolished and the cottage next door and two three-storey terraces were built; one of these was demolished in 1921 and a three-storey brick building known as "Whitehall" was erected on the site.[1]

In 1957, the Director-General of Works (Dr Lodge) suggested to the Governor of the Commonwealth Bank that the site at the top of Martin Place, owned by the Sydney City Council would be suitable for the construction of the head office of the Reserve Bank, and it was subsequently purchased for this purpose. The Bank's administrators called for a design for the building which was contemporary and international, to exemplify a post-war cultural shift away from an architectural emphasis on strength and stability towards a design that would signify the bank's ability to adapt its policies and techniques to the changing needs of its clientele. Before plans were drawn up representatives of the Reserve Bank and the Commonwealth Department of Works made detailed studies overseas into Reserve Bank planning and organisation.[1]

The Sydney Reserve Bank building was designed by the Commonwealth Department of Works, Bank and Special Project Division (Sydney) in 1959 under the direction of a Design Committee consisting of: C. Mc Growther, Superintendent of Reserve Bank Premises; H.I. Ashworth, Consulting Architect (Sydney University); C.D. Osborne, Director of Architecture Department of Works; R.M. Ure, Chief of Preliminary Planning, Department of Works; F.C. Crocker Architect in charge, Bank Section, Dept. of Works; and G.A. Rowe, Supervising Architect, Bank Section, Dept. of Works. The consulting engineer was D. Rudd and Partners and the builder was E.A. Watts Pty Limited. The site was cleared in 1961 and the building was completed by 1964 ready for occupation in January 1965. It was built to accommodate more than 1850 people at a cost of 10 million dollars.[1]

In a press release on the completion of the Reserve Bank headquarters building in Sydney, the then governor, Dr H.C. Coombs highlighted the contemporary design of the building:[1]

"The massive walls and pillars used in the past to emphasise the strength and permanence in bank buildings are not seen in the new head office... Here, contemporary design and conceptions express our conviction that a central bank should develop with growing knowledge and a changing institutional structure and adapt its policies and techniques to the changing community within which it works".

The Reserve Bank design is characteristic of buildings of this era on less constrained sites, where the architect utilised the opportunity to define the base from the shaft using a podium. The building was constructed using a steel frame supporting reinforced concrete floor slabs (using lightweight concrete). This was a solution to the need to produce an economical structural system using a combination of steel and concrete.[1]

The materials used in construction of the Reserve Bank were to be of Australian origin and manufacture. Externally, maintenance and durability determined the choice of marble, granite, aluminium and glass. The facade of the tower had the structural and functional columns expressed as vertical Imperial black granite shafts with Wombeyan marble spandrel panels. The white marble faced pre-cast concrete spandrel panels alternated with recessed windows between the granite columns. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd-floor perimeter beams were faced with Wombeyan marble with a recessed glazed screen wall to the office areas behind a balcony.[1]

Internally decorative ceilings which emphasised the structural bays appeared in buildings of the 1960s and were used in the Reserve Bank. Impressive aluminium decorative ceiling panels emphasised the structural bays of the ground floor public space and lift lobby. The entry and forecourt were paved in Narranderra Grey marble, marble being the most popular stone throughout this period. The ground floor lift lobby walls and internal walls facing the forecourt were clad in Wombeyan marble. The east and west walls of the entry vestibule were clad in Imperial black granite.[1]

Prestige areas for the conduct of important company business in buildings of this period generally had ceilings treated in the same manner as general office ceilings, the exception being the board rooms and executive areas, as is the case in the Reserve Bank where shallow, curved plaster vaults enriched the space. The floor of the board room was paved in Wombeyan white marble. Specially woven heavy-duty wool carpet manufactured in Australia was used in the general office and executive areas.[1]

Walls of the period were often timber panelled, in the Reserve Bank special areas had demountable timber panelling in Queensland black bean and Tasmanian blackwood.[1]

The ground floor, and sometimes mezzanine or first floor levels, of many buildings of this period, accommodated service-based commerce. Often this activity represented a public interface for the owner/occupants of the building. The Reserve Bank was constructed with a four-storey podium divided into two upper floors with projecting horizontal fins and two floors of full height recessed glazing to the mezzanine below. This contained the two-storey public area and the banking chamber in the mezzanine over. Also included in public areas of a number of office buildings of this period was an auditorium or theatrette, and one was included in the Sydney Reserve Bank.[1]

Also included were two residential flats to accommodate senior executives travelling from interstate, a relatively uncommon feature for office buildings of this period.[1]

The building was the central distribution point for notes and coin for New South Wales and Papua New Guinea and the basement included the vaults or strongrooms. They were innovative in their use of concrete and metal sheet to create an impenetrable surround for the strong rooms. The metal strongroom doors are also significant for their size and sophistication.[1]

The Reserve Bank was a prestigious and desirable place to work. There was a strong staff hierarchy and senior positions had considerable community status. This status is demonstrated in physical terms by the design of executive and staff areas in the building. In the 1960s the building was known to provide more extensive staff facilities compared with other contemporary buildings. In this building they consisted of the cafeteria, executive and Board dining rooms, the staff lounge, the staff library, a medical suite, squash courts and associated amenities, an auditorium and an observation deck on the 20th level for the use of staff and ex-staff. A firing range was provided for the training of security guards. The provision of the squash courts and the medical centre would appear to be uncommon facilities provided in multi-storey buildings of this period.[1]

Care was often taken in selecting finishes to areas of staff relaxation, special ceiling finishes were occasionally applied, such as in the case of the Reserve Bank third floor cafeteria where the ceiling was plaster domes in a square grid. Occasionally stone veneers were applied to the walls of these areas, such as in the staff lounge of the Reserve Bank, where slate was used as the wall finish.[1]

The service areas were designed for ease of cleaning and minimal maintenance with vinyl and ceramic tile finishes popular for both floors and walls. The Reserve Bank used ceramic tiles and vinyl to line the walls of service areas and vaults. The floors of the computer and service areas were of vinyl. The Reserve Bank used terrazzo as a floor finish in the toilets. Terrazzo was often used in this way in more prestigious 1960s developments.[1]

The Reserve Bank is also notable for the incorporation of a fire sprinkler system, smoke detectors and fire alarms throughout. All working areas of the building were airconditioned, and notably, the ceiling in the cafeteria was perforated to form a ventilated ceiling which acts as a low-velocity supply air plenum.[1]

The lighting of the Reserve Bank was also notable. Wallwashers were used in the Reserve Bank, where a perimeter strip of recessed fluorescents served to visually detach the ceiling from the wall in the passages and reception area. The opposite effect, that gained by concealing strip fluorescents where they would throw light upwards onto the ceiling, was more uncommon but was used in the office of the Governor of the Reserve Bank. Recessed downlights, both fluorescent and incandescent, were a popular means of lighting areas such as lift lobbies, passages and other public spaces where a softer light than that provided in the general office areas was appropriate, as was the case in the Reserve Bank. Of note was the use of recessed downlights in the cafeteria, set into the interstices of the square grid formed by the shallow cast plaster domes. The lighting of a decorative ceiling was a further area of exploration by architects and lighting engineers of the period. Usually, in the major public area of an office building, elaborate decorative ceilings could be either integrated into the lighting design or the subject of it. The latter was used in the Reserve Bank banking chamber public areas where the lighting is the focus of the decorative ceiling bays. The exterior Reserve Bank emblem was lit by shaped cold cathode tubes which follow the outline of the emblem.[1]

The detailed aesthetic design input into the building extended beyond the building structure and facade treatments and interior design and included ancillary fixtures, fittings and objects for use specifically within the building. These included artworks specially commissioned for the public spaces, furniture, china, flatware, silverware, napery and accessories specifically selected or designed for use within the building. The interior decor and furniture were designed by the Department of Works R.M. Ure and I. Managan, with Frederick Ward, Industrial designer.[1]

Interior furnishings including tables, chairs, couches, credenzas and desks were designed by Fred Ward. Fred Ward (1900–1990) was one of the leaders in modern Australian industrial design of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. During the 1950s, Ward was head of the Australian National University's design department. Around 1961 he resigned from ANU to set up private practice, after being invited by the Reserve Bank Governor Dr H.C. Coombs to undertake the furnishings of several Reserve Bank buildings including Sydney, Canberra, Adelaide and Port Morseby. His furnishings are of a simple and functional design which are now considered to be pieces of art in themselves. Ward also designed the furniture for numerous other important buildings including University House, Canberra, the Academy of Science Building, Canberra and the National Library of Australia, Canberra (with Arthur Robinson).[1]

To further enhance the prestige of the building works of art by Australian artists and sculptors were used. Following an Australia-wide competition, the first prize winners were commissioned to execute their works for the Reserve Bank. The lift foyer features a wall relief by Bim Hilder and the freestanding podium sculpture in Martin Place is by Margel Hinder. Both sculptors were actively engaged in the post-war period designing works for multi-storied office buildings and there was a high degree of co-operation between the artists and architects at this period. Prestige buildings of this period generally commissioned public art highlighting the high profile of the buildings in company marketing strategies and also possibly arising from benevolent policies of these companies.[1]

Bim (Vernon Arthur) Hilder (1909–1990) trained at the East Sydney Technical College and first exhibited his sculptures in 1945. Hilder had worked as a carpenter for Walter Burley Griffin. His murals were styled "wall enrichments in metal". Aside from the Reserve Bank mural (1962–64) he also designed the large mural on the facade of the Wagga Wagga Civic Theatre (1963) and a memorial fountain to Walter Burley Griffin in Willoughby City area (1965). His work is represented in the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the University of New England.[1]

Margel Hinder (1906–1995) was American born moving later to New South Wales. Along with her husband Frank, they contributed to the development of Modernist Australian art focusing on abstraction. They were contemporaries of the Lewers, Ralph Balson, Yvonne Audette, Carl Plate, and Tony Tuckson. Margel Hinder's work is represented in every major Australian Gallery. Her major commissions include the James Cook Memorial Fountain, Newcastle (1966), Northpoint Tower (1970) (now at Macquarie University, Sydney); Woden City Plaza, Canberra; the Western Assurance Co. Building, Sydney (1960); and the State Office Block, Sydney (demolished). Hinder received an Order of Australia in 1979.[1]

Clay from the excavations for the Bank from its initial construction and c. 1974 extension was set aside for the production of a series of commemorative handcrafted pots. These were commissioned from Henry A. Le Grand of Canberra, some were purchased by officers of the Bank and the others were used as decorative elements in the executive suites and remain in the building.[1]

A specially woven tapestry, 10 ft by 5 ft for the Board Room was designed by Margo Lewers and woven in France at the Aubusson workshop in 1968. Entitled "Wide Penetration" the abstract design in blue and yellow was woven in a limited edition of three copies. The tapestry is no longer hung in the Board Room but remains in the Bank's extensive art collection.[1]

A second specially commissioned tapestry was made in 1988 by Sue Batten for display in the Board Room. The tapestry was woven at the Victorian tapestry workshop and the design was inspired by the Bank's Charter and includes elements from the paper 5 dollar note. The tapestry is now hung in the currency display area on the ground floor.[1]

A series of paintings by Australian artists were purchased by the Bank over a period of time and found their permanent home in the executive offices, foyers and hallways of the bank.[1]

On Macquarie Street was a setback created to enable the establishment of a formal Australian Native garden which was designed as the result of a public competition won by Melbourne architect, Malcolm Munro. The garden was flanked on either side by shallow pools and had ornamental gravel surrounds. It was planted with Australian shrubs. This garden feature has now been replaced with landscaping including formal box hedges and flowering shrubs.[1]

Alterations to the building

Between 1974 and 1980 the Reserve Bank was extended to the south, this extension to the original building involved substantial additions on each floor to incorporate the adjacent site to the south. The site consisted of two properties Washington House and Federation House, both properties were demolished for the extension. The addition replicated the original building in height, form, and finishes.[1]

From 1991–1995 upgrading of offices and basement areas, removal of asbestos requiring the stripping of all internal finishes, upgrading of building services and fire protection facilities, new ceilings, lighting and carpets and the extensive restoration and recladding of the external facade of the building.[1]

In November 1993 the original facades were overclad. The original Wombeyan marble cladding was deteriorating due to a combination of weathering and pollution. The new facade was a combination of Australian and Italian stone, with the original Imperial Black granite from South Australia being used for the Columns and Italian Bianco Sardo grey granite for the spandrels. The work was designed by Arup Facade Engineering and was designed to have a minimum visual impact on the building. At the same time, the eastern end of the ground floor was modified from a banking chamber to form the public exhibition area.[1]

In 2000 the Parliamentary Committee on Public Works approved changes to the building included conversion of the staff cafeteria, auditorium and staff facilities (level 3) to office accommodation; demolition of the two residential flats and creation of new cafeteria space; removal of the two squash courts and plant equipment (level 17) and conversion to office use including lowering of the high level windowsills to the north elevation and enlarging of existing recessed marble panels to windows on the south facade; conversion of level 19 ancillary space to office use; and removal of the firing range.[1]

Description

The Reserve Bank building is at 65 Martin Place, corners with Macquarie and Phillip Streets, Sydney, a prominent corner position fronting Martin Place between Macquarie Street and Phillip Street.[1]

The Reserve Bank 1964, is a refined example of the Post War International style. The building is a 22-storey high-rise tower with three-level basement. It is constructed of a steel frame concrete encased with reinforced concrete slabs. The building contains some unusually long cantilever beams on the 1st to 3rd floors. The Reserve Bank provides a notable example of a characteristic of buildings of this era on less constrained sites, where the architect utilised the opportunity to define the base from the shaft using a podium. The Reserve Bank has a four-storey podium divided into two upper floors with projecting horizontal fins and two floors of full height recessed glazing to the mezzanine below. The building is entered via a bronzed railed grey and black granite terrace with steps to accommodate the site slope and adjacent footpath.[1]

The tower section above the second floor is set back from the site boundaries on the three street frontages. The rectangular building floor plate surrounds a central bank of lifts. The tower is capped with recessed balconies to level 20. Above this is a roof terrace with full height glazing and extensive cantilever roof.[1]

The facade treatment of the building is distinctive and derives from both the modular design created to allow office subdivision which is expressed in the window mullions and the use of materials including the extensive use of natural stone. The vertical columns faced in black granite and aluminium define the eight bays of the tower and extend up to form the supports for the balconies. The use of black polished granite cladding was a popular choice of the time, the Reserve Bank used Imperial Black granite for the columns. The subdivision of the facade into smaller vertical bays was characteristic of buildings where sun control was a central concern. Between the columns spandrel panels in grey granite alternated with recessed glazing. The glazing panels stop short of the corner.[1]

The basements contain vehicular access areas, the main switchboard as well as the three main strongrooms and a series of voucher stores and cash handling areas. Originally they also contained extensive plant areas. The Strong Rooms are located in the basement originally used for the storage of bullion and cash. They have a degree of technical significance for their innovative use of concrete and metal sheet to create an impenetrable surround for the strong rooms. The metal strong room doors are significant for their size and sophistication.[1]

The ground floor is symmetrical around the central main vestibule which is a two-storey volume with a general banking chamber on the western side and a public display area on the eastern side. The display area replaces the former Bonds and Stock Banking Chamber of the original design. The ground level entrance foyer/vestibule remains substantially intact including internal finishes of Wombeyan marble to the south wall, granite floor, east and west Imperial granite walls including high-level glazing, anodised aluminium ceiling and the south wall relief by Bim Hilder. Alterations include the introduction of a security desk, new entrance doors, and reconfigured glazing.[1]

The mezzanine is set back from Martin Place frontage creating an atrium over the ground floor. With the first and second floors it forms a podium from which the office tower springs. The third floor housed the staff amenities area with a staff cafeteria and kitchen, an auditorium and staff library and a staff lounge outside the lift foyer. These areas were originally designed with a distinctive character which has now been altered by later refurbishments. The eleventh floor contains the board room (featuring a marble floor), board dining room, board members common room and reception and meeting areas. The twelfth floor contains the governor's suite, reception areas and executive suites.[1]

The 16th floor housed two residential flats, but the flats have been removed in recent works. The floor also included the medical centre. The 17th to 19th floors held two squash courts and an observation gallery was located along the northern facade. These were all removed in recent works. The 20th floor houses staff amenities. Most lift foyers are marble lined, Level 3 is timber.[1]

Some of the original furniture designed for the building including tables, chairs, couches, credenzas and desks remain within the public spaces, offices and special areas of the building.[1]

The Westpac (former Bank of NSW) building erected on the opposite corner to the Reserve Bank occupies a similar footprint and has a similar mass, providing a gateway effect at the top of Martin Place.[1]

Public art

The main entrance foyer features an expansive wall relief by Bim Hilder. It is made up of many separate small parts of beaten copper and bronze. One section of it incorporates a six-inch piece of quartz crystal uncovered by geologist Ben Flounders in South Australia's Corunna Hills. Another displays semi-precious stones. The Martin Place forecourt features a freestanding podium sculpture by Margel Hinder. The Podium sculpture is a 26 ft high freestanding sculpture. It is unnamed and has no banking reference, but was designed to complement the architecture of the building. It is welded sheet copper on a stainless steel structural frame with molten copper decoration. The original design Maquette is also located in the Bank. Other important elements include the brass lettering text of the Bank's 1959 charter set on a black granite wall in the main foyer; the opening commemorative plaque; the Bank emblem originally located on the western parapet wall of the building constructed in cast aluminium with green enamelled finish designed by Gordon Andrews (now removed); the portrait of Dr H. C Coombs, the first Governor by Louis Kahan purchased in 1964.[1]

Condition

In general, the building retains its early appearance and character despite having undergone considerable alterations and modification. Internal finishes have been considerably altered in many locations, and have been replaced with new finishes. Internally the building has been remodelled at the upper office levels. The boardroom and the lift foyers have remained largely intact. The ground level double volume spaces are intact; however, there has been substantial alteration to furniture and fittings. The original marble ceiling panel has been replaced in metal.[1]

Comparison

In addition to the Head Office, branch offices were constructed in the central business districts of each of the state capital cities, as well as in Canberra and Darwin during the 1960s and 1970s. A number of purpose-designed office buildings were erected to designs by the Commonwealth Department of Works Banks and Special Projects Branch as part of the initial establishment of the Reserve Bank of Australia.[1]

The buildings in Darwin and Brisbane have been sold. The Reserve Bank still owns the buildings in Perth and Hobart (sold 2001), Adelaide, Canberra, and Melbourne. The buildings constructed throughout Australia by the Bank during the 1960s reflected a confidence in things Australian and in the future.[1]

The Canberra Branch building of the Reserve Bank was the result of an architectural competition, managed by the National Capital Development Commission. Howlett and Bailey from Perth won the competition from 131 submissions. It was constructed by Civil & Civic and completed in 1965. Also of a contemporary design, the Canberra building is in the Stripped classical style. The architectural qualities of the Canberra Reserve Bank building rely on the lightness of the structure, the regular structural pattern, the contrast between the marble-faced columns and beams and the receding pattern of the glazing. The vertical effect imparted by the columns extending over two levels gives the low rise building a sense of height and is most effective. The columns are cruciform in plan and support a beam carefully separated from the column. The glazed curtain wall is supported on the beam and uses aluminium mullions. The very strong, blank wall of the secure ground floor cash handling area on the external southeastern side of the building is another powerful reminder of its modernist qualities where the internal function gains external expression. Internally the most important space is the banking chamber. It is a symmetrical design with a central entrance under a canopy with black slate entrance floor, converting into carpet once inside the room.[1]

The Reserve Bank, Adelaide, was built in 1963-65 to a design by the Commonwealth Department of Works architects C.D. Osborne, R.M. Ure, G.A. Row and F.J. Crocker. It is constructed from largely Australian building materials of high quality including Wombeyan marble, South Australian black granite and Victorian Harcourt grey granite. Of particular interest is the building's inward curving wall to both the east and west elevations.[1]

Heritage listing

The Reserve Bank building (1964) designed by the Commonwealth Department of Works, Bank and Special Project Section, is highly significant in the development of post World War II multi-storey office buildings in Australia. It is a significant example of a 1960s office building notable as being a well-designed example of the International style; its construction using high-quality Australian materials; steel and concrete construction; and interior design details and artworks. The building's significance has been retained through a major extension (1974–1980), recladding (1993) and internal refitting. Through its prestigious design and function as Australia's central bank, the building makes an important contribution to the streetscape and character of Martin Place, Macquarie Street and Phillip Street.[1]

Reserve Bank was listed on the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List on 22 June 2004 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

Criterion A: Processes

The Reserve Bank building (1964) designed by the Commonwealth Department of Works, Bank and Special Project Section, is highly significant in the development of post World War II multistorey office buildings in Australia. The building's significance has been retained through a major extension (1974–1980), recladding (1993) and internal refitting. The Reserve Bank building is of historical significance in its ability to demonstrate the changing functions and role of the Reserve Bank of Australia, particularly that of the head office, since 1964. The International style of the building represents the post-war cultural shift within the banking industry, away from the traditional architectural emphasis on strength and stability towards a more contemporary and international style.[1]

The two foyer artworks are of historical and aesthetic significance. The artworks by Bim Hilder and Margel Hinder are significant examples of Australian modernist sculpture of this period by two significant artists, who were selected as the winners of design competitions by the Reserve Bank. The furnishings by Fred Ward are of historical and aesthetic significance. Designed for the building by Ward, who was one of the leaders in modern Australian industrial design at this time, the furnishings are of a simple and functional design which are now considered to be pieces of art in themselves.[1]

When constructed elements of the mechanical and electrical services within the building were considered advanced and innovative, and although many elements have been removed or substantially altered, their incorporation in the building is still of interest today, this included the fire sprinkler system, smoke detectors and fire alarms; interior and signage lighting; and airconditioning.[1]

The provision of two residential flats, for use by visitors to the bank; squash courts; and firing range were relatively uncommon for the time (all removed 2001). The two doors to the main strongroom were at the time of construction the largest and most technically advanced in the southern hemisphere.[1]

Criterion B: Rarity

When constructed elements of the mechanical and electrical services within the building were considered advanced and innovative, and although many elements have been removed or substantially altered, their incorporation in the building is still of interest today, this included the fire sprinkler system, smoke detectors and fire alarms; interior and signage lighting; and airconditioning.[1]

The provision of two residential flats, for use by visitors to the bank; squash courts; and firing range were relatively uncommon for the time (all removed 2001).[1]

Criterion D: Characteristic values

The Reserve Bank building (1964) designed by the Commonwealth Department of Works, Bank and Special Project Section, is highly significant in the development of post World War II multi-storey office buildings in Australia. It is a significant example of a 1960s office building notable as being a well-designed example of the International style; its construction using high-quality Australian materials; steel and concrete construction; and interior design details and artworks. The building's significance has been retained through a major extension (1974–1980), recladding (1993) and internal refitting[1]

Criterion E: Aesthetic characteristics

Through its prestigious design and function as Australia's central bank, the building makes an important contribution to the streetscape and character of Martin Place, Macquarie Street and Phillip Street.[1]

Criterion F: Technical achievement

The Reserve Bank building is highly significant in the development of post World War II multi-storey office buildings in Australia for its use of high-quality Australian materials; steel and concrete construction; and interior design details and artworks.[1]

The furnishings by Fred Ward are of historical and aesthetic significance. Designed for the building by Ward, who was one of the leaders in modern Australian industrial design at this time, the furnishings are of a simple and functional design which are now considered to be pieces of art in themselves[1]

The variety of moveable heritage items located throughout the building including furniture, china, flatware, silverware, napery and accessories, pottery, tapestry and artworks are significant having been specifically designed or purchased for the building as well as being of artistic merit in their own right.[1]

When constructed elements of the mechanical and electrical services within the building were considered advanced and innovative, and although many elements have been removed or substantially altered, their incorporation in the building is still of interest today, this included the fire sprinkler system, smoke detectors and fire alarms; interior and signage lighting; and airconditioning.[1]

The two doors to the main strongroom were at the time of construction the largest and most technically advanced in the southern hemisphere.[1]

Criterion G: Social value

The building has social significance being regarded by the Australian community as the home of the Reserve Bank function and the place where significant economic policy is carried out on behalf of the nation.[1]

Criterion H: Significant people

The artworks by Bim Hilder and Margel Hinder are significant examples of Australian modernist sculpture of this period by two significant artists, who were selected as the winners of design competitions by the Reserve Bank. The furnishings by Fred Ward are of historical and aesthetic significance. Designed for the building by Ward, who was one of the leaders in modern Australian industrial design at this time, the furnishings are of a simple and functional design which are now considered to be pieces of art in themselves[1]

The Reserve Bank head office building is associated with successive governors of the Reserve Bank: Dr. H.C. Coombs; J.G. Phillips (KBE); H.M. Knight KBE DSC; R.A. Johnston (AC); B.W. Fraser and I.J. Macfarlane. The building is also associated with personnel of the Commonwealth Department of Works, Banks and Special Projects branch, responsible for the building's design in particular: C. McGrowther; Professor H.I. Ashworth; C.D. Osborne; R.M. Ure; F.C. Crocker; G.A. Rowe; as well as E.A. Watts (builders for both stages of construction) and Frederick Ward (furniture designer).[1]

References

- "Reserve Bank (Place ID 105456)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Architecture in Australia "Reserve Bank of Australia" September 1966.

- Australian Heritage Commission, Register of the National Estate, Place Reports for Reserve Bank, Canberra and Reserve Bank, Adelaide.

- City of Sydney, Heritage Database Inventory Report "Reserve Bank".

- Drill Hall Gallery Catalogue "Fred Ward: A selection of Furniture and Drawings" Drill Hall Gallery: 2 May-16 June 1996.

- Noel Bell Ridley Smith & Partners Pty Ltd. "The Reserve Bank 65 Martin Place Sydney 2000 Conservation Management Plan" June 2001.

- Proposed headquarters, Sydney, for the Reserve Bank of Australia. 1959. Folios F 725.24099441

- Royal Australian Institute of Architects, Register of Twentieth Century Buildings of Significance: "Heritage Inventory Report: Reserve Bank, 2000".

- Staples, M. "From Pillar to Post: Regional heritage and the erasure of Modernist architecture" in Rural Society Journal Volume 9 No 1, 1999.

- Taylor, J. "Post World War II Multistoried Office Buildings in Australia (1945–1967)" Report. For the Australian Heritage Commission 1994.

- Woodhead International & Noel Bell Ridley Smith & Partners Architects Pty Limited. "Revised Statement of Heritage Impact: Reserve Bank of Australia- Head Office Consolidation, 65 Martin Place, Sydney, New South Wales". Revised May 2001.

Other sources of information

- Bloomfield Galleries: Information on Margel Hinder

- Information on Fred Ward from the Drill Hall Gallery.

- Reserve Bank of Australia Web site www.rba.gov.au

Attribution

![]()

External links

![]()