Reid's paradox of rapid plant migration

Reid's Paradox of Rapid Plant Migration or Reid's Paradox, describes the observation from the paleoecological record that plant ranges shifted northward, after the last glacial maximum, at a faster rate than the seed dispersal rates commonly occur.[1][2] Rare long-distance seed dispersal events have been hypothesized to explain these fast migration rates, but the dispersal vector(s) are still unknown. The plant species' geographic range expansion rates are compared to the actualistic rates of seed dispersal using mathematical models, and are graphically visualized using dispersal kernels.[2][3] These observations made in the paleontological record, which inspired Reid's Paradox, are from fossilized remains of plant parts, including needles, leaves, pollen, and seeds, that can be used to identify past shifts in plant species' ranges.

Reid's Paradox is named after Clement Reid, a paleobotanist, who made the principle observations from the paleobotanical record in Europe in 1899. His comparison of oak tree seed dispersal rates, and the observed range of oak trees from the fossil record, did not concur. Reid hypothesized that diffusion was not a possible explanation for the observed paradox, and supplemented his hypothesis by noting that birds were the likely cause of long range seed dispersal.[1] Reid's Paradox has been subsequently documented across Europe and North America.[2][3][4]

Dispersal kernels

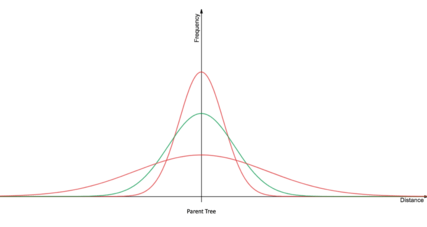

Dispersal kernels are statistical models that represent the probability of seed dispersal from the source tree. Realistic biological data is required to complete the models. These data are used to accurately fill in variables such as seed number, seed size, and reproductive age.[3] Depending on the plant species, the variables in the equation will change. In the years since Reid hypothesized the methods for seed dispersal, the models have gained more complex elements which attempt to resolve Reid's Paradox.[2]

The dispersal of seeds from a parent tree are initially occurs as a normal distribution, as predicted by a standard diffusion equation. However, biological phenomenon complicate the diffusion equation by adding biotic vectors of dispersal such as blue jays and eastern grey squirrels, species which possess caching behaviors, and abiotic agents of dispersal such as high velocity wind storms.[2] These additional vectors of seed dispersal make the dispersal kernels have a "fat-tail", or a large kurtosis. This means that the probability of a long-range dispersal event is higher than that of the standard diffusion dispersal kernel.[2][3][5] In order to resolve Reid's Paradox, the vector(s) of seed-dispersal, which give the dispersal kernel a fat-tail, must be identified.

Possible explanations for Reid's Paradox

Animal dispersal

Long distance seed-dispersal events due to animal-seed interactions (such as caching or endozoochorous dispersal) would fatten the tail of the dispersal kernels. To fully explain Reid's Paradox, these rare animal induced seed-dispersal events must have been more important during migration events than recognized or recorded currently.[1][3]

Cryptic refugia

Small populations of plants may have grown closer to the ice sheets in microhabitats that possessed the habitat characteristics needed for growth and reproduction. This would minimize the actual post-glacial dispersal distance. Such hypothetical populations would not be abundant enough to leave fossil evidence, so have escaped detection. In North America, there is some genetic evidence of cryptic northern refugia for sugar maple and American beech.[6][4]

References

- Reid, Clement (1899). The origin of the British flora. Gerstein - University of Toronto. London Dulau.

- Clark, James S.; Fastie, Chris; Hurtt, George; Jackson, Stephen T.; Johnson, Carter; King, George A.; Lewis, Mark; Lynch, Jason; Pacala, Stephen; Prentice, Colin; Schupp, Eugene W. (January 1998). "Reid's Paradox of Rapid Plant Migration". BioScience. 48 (1): 13–24. doi:10.2307/1313224. JSTOR 1313224.

- Clark, James S. (August 1998). "Why Trees Migrate So Fast: Confronting Theory with Dispersal Biology and the Paleorecord". The American Naturalist. 152 (2): 204–224. doi:10.1086/286162. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 18811386.

- Cruzan, Mitchell B.; Templeton, Alan R. (December 2000). "Paleoecology and coalescence: phylogeographic analysis of hypotheses from the fossil record". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 15 (12): 491–496. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(00)01998-4. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 11114435.

- Powell, James A.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E. (February 2004). "Multiscale Analysis of Active Seed Dispersal Contributes to Resolving Reid's Paradox". Ecology. 85 (2): 490–506. doi:10.1890/02-0535. ISSN 0012-9658.

- Rull, Valentí (2010-06-21). "On microrefugia and cryptic refugia: Correspondence". Journal of Biogeography: no. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02340.x.