Reed (mouthpiece)

A reed is a thin strip of material that vibrates to produce a sound on a musical instrument. Most woodwind instrument reeds are made from Arundo donax ("Giant cane") or synthetic material. Tuned reeds (as in harmonicas and accordions) are made of metal or synthetics. Musical instruments are classified according to the type and number of reeds.

The earliest types of single-reed instruments used idioglottal reeds, where the vibrating reed is a tongue cut and shaped on the tube of cane. Much later, single-reed instruments started using heteroglottal reeds, where a reed is cut and separated from the tube of cane and attached to a mouthpiece of some sort. By contrast, in an uncapped double reed instrument (such as the oboe and bassoon), there is no mouthpiece; the two parts of the reed vibrate against one another.

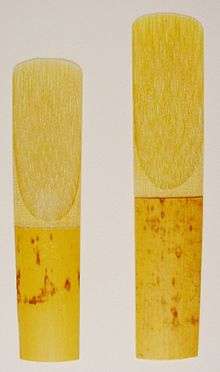

Single reeds

Single reeds are used on the mouthpieces of clarinets and saxophones. The back of the reed is flat and is placed against the mouthpiece, the rounded top side tapers to a thin tip. These reeds are roughly rectangular in shape except for the thin vibrating tip, which is curved to match the curve of the mouthpiece tip. All single reeds are shaped similarly but vary in size to fit each instrument's mouthpiece.

Reeds designed for the same instrument may look identical, but vary in thickness ("hardness" or "strength"). Hardness is generally measured on a scale of 1 through 5 from softest to hardest. This is not a standardized scale and reed strengths vary by manufacturer. The thickness of the tip and heel and the profile in between affect the sound and playability. Cane of different grades (density, stiffness), even if cut with the same profile, also respond differently due to natural differences in cane fiber density.

How single reeds are made

The cane used to make reeds for saxophone, clarinet, and other single-reed instruments grows in the southern coastal regions of France and Spain—and in the last 30 years, in the area of Cuyo in Argentina. After growers cut the cane, they lay it out in direct sunlight for about a month to dry. They rotate the cane regularly to ensure even and complete drying. Once dry, growers store the cane in a warehouse. As reed production requires it, workers pull the cane from the warehouse and take it to the factory—to the cutting department, which cuts it into tubes and grades the tubes by diameter and wall density.[1] They then cut the tubes into splits, and make those into reed blanks. They taper and profile the blanks into reeds using blades or CNC machines. A machine grades completed reeds for strength.

Double reeds

Double reeds are used on the oboe, oboe d'amore, English horn, bass oboe, Heckelphone, bassoon, contrabassoon, sarrusophone, shawm, bagpipes, nadaswaram and shehnai. They are typically not used in conjunction with a mouthpiece; rather the two reeds vibrate against each other. However, in the case of the crumhorn, bagpipes, and Rauschpfeife, a reed cap that contains an airway is placed over the reeds and blown without the reeds actually coming in contact with the player's mouth. Reed strengths are graded from hard to soft.

How double reeds are made

The making of double reeds begins in the same way as how single reeds are made. The cane is collected from Arundo donax, dried, processed and cut down to manageable sizes for reed-making. Similar to single reed production, the cane is separated into various diameters.[1] The most common diameters for American-style oboe reeds are as follows: 9.5–10 mm (0.37–0.39 in), 10–10.5 mm (0.39–0.41 in), and 10.5–11 mm (0.41–0.43 in).[2] Many American oboists prefer a specific diameter at one time of the year and a different diameter at other times, depending on the season and the weather.[3]

They then split the tubes into three equal parts, picking out the pieces that are not warped. A reed made from a piece of warped tube cane won't vibrate consistently on both sides, affecting the sound.[4] After the cane is split, the pieces are gouged in a gouging machine to remove many cane layers to drastically decrease thickness. This eases the scraping process for the reed-maker, and helps maintain sharper knives. Reed makers not only learn to master reed making, but also learn how to sharpen knives with great skill.[5]

Finally, the gouged pieces of cane soaked and "shaped" on a shaper with razor blades and allowed to dry before the final steps. The shaped piece of cane is then re-soaked and tied onto a "staple" for oboe reeds and formed on a mandrel for bassoon reeds. Bassoon reeds are wrapped with nylon thread or cotton thread, depending on the musician's preference. Oboe reeds are most commonly tied with nylon thread. Finishing both bassoon and oboe reeds requires the reed-maker to scrape along the cane section of the reed with a scraping knife to specific dimensions and lengths depending on the reed style and the musician's preference. Bassoon and oboe reeds are finished when the reeds play in tune or can make a sufficient "crow"-like noise.[6]

Quadruple reeds

Quadruple reed instruments have four reeds, two on top and two on bottom. Examples of this include an archetypal instrument from India, the shehnai, as well as the pi from Thailand, and the Cambodian sralai. Having four reeds instead of two produces a very different tone and set of harmonics.

Free reeds

There are two types of free reeds: framed and unframed. Framed free reeds are used on ancient East Asian instruments such as the Chinese shēng and Japanese shō, ancient Southeast Asian instruments like the Laotian khene, and modern European instruments such as the harmonium or reed organ (consisting of reed pipes), harmonica, concertina, bandoneón, accordion, and Russian bayan. The reed is made from cane, willow, brass or steel, and is enclosed in a rigid frame. The pitch of the framed free reed is fixed.

The ancient bullroarer is an unframed free reed made of a stone or wood board tied to a rope that is swung around through the air to make a whistling sound. Another primitive unframed free-reed instrument is the leaf (the bilu), used in some traditional Chinese music ensembles. A leaf or long blade of grass is stretched between the sides of the thumbs and tensioned slightly by bending the thumbs to change the pitch. The tone can be modified by cupping the hands to provide a resonant chamber.[7]

Materials

Most woodwind instrument reeds are made from cane, but synthetic reeds are used by a small number of clarinetists, saxophonists, double reed players, and bagpipers. Synthetic reeds are generally more durable and do not need to be moistened prior to playing. However, many players consider them to have inferior tone.

Recent developments in synthetic reed technology have produced reeds made from synthetic polymer compounds , and reeds with both cane and synthetic compounds combined . As technology in this area has progressed, synthetic reeds have gained more acceptance. Synthetic reeds are useful when the instrument is played intermittently with long breaks in between, during which time a natural reed might dry out.

The dizi, a Chinese transverse flute, has a distinctive kind of reed (a di mo), which is made from a paper-like bamboo membrane.

Commercial vs. handmade

Musicians originally crafted reeds from cane using simple tools, a time-consuming and painstaking process. Specialized tools for cutting and trimming reeds by hand reduce the time needed to finish a reed. Today, nearly all single-reed instrument players buy manufactured reeds, though many adjust them by shaving or sanding. Some professionals make single reeds from blanks, but this is time-consuming and can require expensive equipment. Among double reed players, advanced and professional players typically make their own reeds, while beginners and students often buy reeds, either from their teachers or from commercial sources.

Care and maintenance

Reeds made from cane, used on woodwind instruments such as saxophones, clarinets, oboes, and bassoons, are affected highly by climate changes. Reeds change with temperature and humidity. It is common for a reed to behave very differently between, for example, a cold rehearsal room and a warm stage. While these changes are unavoidable, the musician can adjust and compensate.

Manufacturers produce reeds in different strengths, indicated by a number (most commonly 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, and 5).[8] The strength is determined by a machine in the reed-making process that presses against the vamp (the part of the reed that includes the tip, where the tongue is placed, and the heart just behind the tip) of the reed and determines how stiff the reed is. The machines separates the reeds according to strength. A box of strength-3 reeds may include reeds of strengths ranging from 2.75 to 3.25. Often, in a box of ten reeds, not every reed is usable.

Because reeds change with climate, reeds that are too soft can be kept in the hopes that they eventually thicken, but there is nothing else that can be done. If a reed is too stiff, however, there are solutions. The most simple solution is to turn a piece of paper over so there is no ink and gently rotate the reed around it while gently placing the fingers at the tip and the butt to ensure even distribution on the paper. This works if the reed is just barely too stiff or warped (the tip is not flat). If the reed is more than a little too stiff, sandpaper can be used (preferably 300–500 grain) to repeat the process as described. Be careful not to damage the tip of the reed.

It is also advised to wet your reed before use either with saliva or dousing it in water.

Sometimes a reed does not play well because it was not cut properly (machine error). This cannot always be fixed, but it can be helped with a reed pen. Reed pens are expensive, but can be used to realign or recut the filing on the reed.

To get the longest life from a reed,[9] the reed should be soaked in water for two minutes or until fully moist, but not soaked. It should be played for about five minutes the first day, 15 minutes the second, and 45 minutes the third. After this, it should continue to be soaked, but can be played as long as needed.

"Reed players"

Especially in musical theatre orchestras, woodwind players are commonly referred to as "reed players" or "reeds". These players are not restricted to one particular woodwind instrument group, but play ("double on") several different instruments. (Although the flutes are not reed instruments, they are included as well.)

There are usually only four or five reed players in a pit orchestra who perform on all woodwind instruments (flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, saxophone). A basic reed part usually has three or four instruments (flutes, clarinets and saxophones being the most common), but can include up to eight instruments, such as the "Reed 3" part in Bernstein's West Side Story, which calls for the player to use piccolo, flute, oboe, English horn, clarinet, bass clarinet, and tenor and baritone saxophones. Through intricate doubling, the arranger can simulate the sound of a much larger woodwind section. (The West Side Story woodwind section would require twelve "classical" players instead of five "reed" players.)

See also

- Reed aerophones

- Free-reed instrument

- Mouthpiece (woodwind)

- Uilleann pipes reed-making workshops in Ireland.

Notes

- "YouTube Search Powered by iBoss". www.cleanvideosearch.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Oboe Cane Processing Overview | Midwest Musical Imports Blog". Midwest Musical Imports. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- "Oboe Tube Cane Guide :: Midwest Musical Imports Blog". Midwest Musical Imports. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- Witt, John (2014-07-03). "Oboe Reed Vibrations - Things Are Shakin' - OboeHobo". OboeHobo. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- "The Westwind reed knife and sharpening system". Westwind Reed Making Tools. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- "Reed Help for Beginners". www.fredonia.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- Henry Doktorski, "The Classical Squeezebox: A Short History of the Accordion and Other Free-Reed Instruments in Classical Music," The Classical Free-Reed, Inc. (1997).

- "D'Addario Woodwinds : Strength Comparison Chart". www.woodwinds.daddario.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-16. Retrieved 2015-04-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

- The Roots of Reeds - an exhibition curated by the Museum of Making Music, Carlsbad, CA - detailing the history and migration of reed instruments.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.