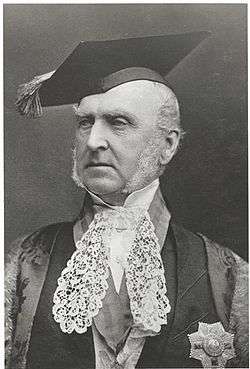

Redmond Barry

Sir Redmond Barry, KCMG QC (7 June 1813 – 23 November 1880), was a colonial judge in Victoria, Australia of Anglo-Irish origins. Barry was the inaugural Chancellor of the University of Melbourne, serving from 1853 until his death in 1880. He is arguably best known for having sentenced Ned Kelly to death.[1]

Early life

Barry was the third son of Major-General Henry Green Barry, of Ballyclough, County Cork, Ireland, and his wife Phoebe Drought, daughter of John Armstrong Drought and Letita Head. Barry had five brothers and six sisters and was educated at a military school, Hall Place, near Bexley, in Kent.[2] Returning to Ireland in 1829, he was unable to obtain a military commission so began his own further education. Following his own classics programme, translating classical authors into English verse, reading old and new writers, he gained a working knowledge of nearly every subject.

In 1832, he entered Trinity College, Dublin, graduated in 1835 with the usual Bachelor of Arts degree, and was called to the bar in Dublin in 1838.[3][4]

After his father's death, Barry sailed for Sydney, capital of the British Colony of New South Wales.

Life and work in Australia

Barry arrived in New South Wales in April 1837 and was admitted to the New South Wales Bar.[5] After two years in Sydney, Barry moved to Melbourne, a city with which he was ever afterwards closely identified, arriving at the new Port Phillip Settlement on 13 November 1839.[5]

In 1841, Barry served as the defence lawyer for Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, two indigenous rebels on trial for murder. Barry questioned the legal basis of British authority over Aborigines who were not citizens and claimed that the evidence was dubious and circumstantial. Despite his best efforts, the two men were found guilty and subsequently hanged on 20 January 1842, becoming the first people in Victoria to be legally executed.[6][7]

After practising his profession for some years, he became commissioner of the Court of Requests, and after the creation in 1851 of the colony of Victoria, out of the Port Phillip district of New South Wales, he became the first Solicitor-General of Victoria, with a seat in both the Legislative and Executive Councils.[4] In 1852 he was appointed a judge of the Supreme Court of Victoria. Later he also served as acting Chief Justice and Administrator of the government.

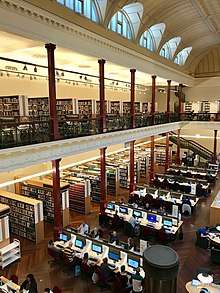

Barry was noted for his service to the community, and he convinced the state government to spend money on public works, particularly on education. He was instrumental in the foundation of the Royal Melbourne Hospital (1848), the University of Melbourne (1853), and the State Library of Victoria (1854).[4] He served as the first chancellor of the university until his death and was also president of the trustees of the State Library. He was the first President of the Ballarat School of Mines (1870), which later became the Ballarat University and now Federation University Australia.[8]

Barry was the judge in the Eureka Stockade treason trials in the Supreme Court in 1855. The thirteen miners were all acquitted.

In 1857, Barry conducted the inquest into the murder of Inspector-General John Giles Price, who was beaten to death by a group of at least 15 convicts during an inspection of the prison quarries in Williamstown, Victoria. Seven of the convicts involved in the attack on Price were found guilty, and sentenced to death by hanging. The seven men were executed at Melbourne Gaol within a three-day period from April 28 to April 30.[9]

He chaired the committee for the Victorian Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne,[10] represented Victoria at the London International Exhibition of 1862 and at the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876.[4] He was made a knight bachelor in 1860, and was created a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in 1877.[4]

Kelly cases

In October 1878, at Beechworth court, Barry presided over a case in which Mrs Ellen Kelly (King) and two men were accused of aiding and abetting the attempted murder of a Victoria Police constable named Alexander Fitzpatrick. After sentencing Mrs Kelly to three years with hard labour, Barry said, 'if your son Ned were here I would make an example of him for the whole of Australia – I would give him fifteen years'.

In 1880, Barry presided at the final trial of Ned Kelly, who was tried and convicted of murdering three other Victoria Police constables. The trial and sentencing have since been the subject of many articles and books by lawyers and historians. When he sentenced Kelly to death by hanging, Barry uttered the customary words "May God have mercy on your soul". According to the transcripts, Kelly replied "I will go a little further than that, and say I will see you there when I go". On 23 November 1880, only twelve days after Kelly's execution, Sir Redmond Barry died from what the doctors described as 'congestion of the lungs and a carbuncle in the neck'.

Contribution to libraries

Barry laid the foundations of the Supreme Court Library (Melbourne)[11] and was the prime mover establishing the Melbourne Public Library. As a legislator he promoted the Parliamentary Library. He organised the Governor, Sir Charles Hotham, to lay the foundation stones of University of Melbourne, Melbourne Public Library and Sunbury Industrial School [later Sunbury Lunatic Asylum] in 1854 – all on the same day.[12]

Sir Redmond Barry virtually single-handedly planned the Melbourne Public Library building and its contents. He had a 'hands-on' approach personally writing book selection and acquisition procedures – even to getting his hands dirty shelving books for the Library's 1856 opening. In 1862 and 1877-78 he went to Europe, England and America, purchasing books and pictures for University, Law and Public Libraries and Art Gallery. As Board of Trustees Chairman he was responsible for starting travelling libraries and supporting extended library hours. In September 1870 he "acquired" Marcus Clarke as Public Library Trustees clerk (later secretary), who until his death in 1881 worked as sub-librarian.

There can be fewer men with greater concern for and a greater and better vision for the young colonial society in which Redmond Barry made his life.[13] Books and reading were intrinsic to Barry's own educational and intellectual development so he wanted these advantages for other people. The reason for his support of the Melbourne Public Library, the Law Library and his support of Mechanic Institutes was free access to libraries for all not just a select few.

Personal life

Barry never married, but had four children to Louisa Barrow, all of whom he acknowledged and supported.[1]

Death

The Argus reported Sir Redmond Barry had been suffering from diabetes for about 10 years, but on his return from his trip to Europe and America it was apparent that the disease had affected his system. On Monday, 15 November, he was first troubled with the carbuncle on his neck. Sir Redmond was counselled by his medical adviser to at once rest from duty, but he was reluctant to do so, and continued to attend the court until he was compelled to take rest. He was constantly attended by Dr. Gunst, who however, could scarcely impress his patient with a sense of the very serious nature of his disease, which he regarded somewhat lightly. He became restless, and it was deemed advisable to place him under the constant care of a nurse. Despite the precautions, Barry caught cold through exposure, and congestion of the left lung set in. Dr. Gunst held a consultation with Dr. Teague, and pronounced the case hopeless. The left lung had become greatly congested, and this, together with the exhaustion and wasting away of the system resulting from the previous disease, proved fatal.[14]

Memorials and legacy

The State Library of Victoria has named a reading room after Sir Redmond Barry, who was the first Chair of the Board of Trustees of the Melbourne Public Library. The University of Melbourne of which he was the first Chancellor has a Redmond Barry building named for him. A plaque marking the location of Sir Redmond Barry's residence is located near the corner of Josephine Avenue and High Street Road in Mount Waverley. The University of Melbourne has also established the Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor, a title awarded to professors within the university who display outstanding research and leadership.[15]

The Australian Library and Information Association's highest honour that can be bestowed on an individual not eligible for membership of the association is the Redmond Barry Award, awarded in recognition of outstanding service to or promotion of a library and information service or libraries and information services, or to the theory or practice of library and information science, or an associated field.[16]

Portrayals in film

Barry has appeared as a character in three dramatizations of the Ned Kelly story: He appears in Tony Richardson's 1970 biopic about the bushranger, played by acting veteran Frank Thring.[17] He has a prominent role in the 1977 television drama The Trial of Ned Kelly, where he was played by John Frawley.[17] And he appeared in the 1980 miniseries The Last Outlaw, played by David Clendinning.[18] Barry is also a minor character in Philippe Mora's bushranging biopic Mad Dog Morgan, where he is played by Peter Collingwood.

Works

See also

- Judiciary of Australia

- List of Judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria

References

- Ryan, Peter (1969). "Barry, Sir Redmond (1813–1880)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "HIS HONOR SIR REDMOND BARRY, KT., M.A., LL.D., &c". Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 29 February 1872. p. 63. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- "SIR REDMOND BARRY, K.C.M.G., LL.D." The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 24 November 1880. p. 5. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

-

- Galbally, Ann, Redmond Barry: An Anglo-Irish Australian (Carlton, Vic., Melbourne University Press, 1995)

- Perkins, Miki (7 June 2012). "Call for memorial for first men hanged in Melbourne". The Age.

- Wikipedia page: Tunnerminnerwait

- "The School of Mines and Industries Ballarat - A guide to heritage buildings at the SMB campus in Lydiard Street South, Ballarat" (PDF). The University of Ballarat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Barry, John Vincent; The Life and Death of John Price: A Study of the Exercise of Naked Power; Melbourne University Press; 1964

- "Account of the Victorian Exhibition of 1875 an 8 page supplement in The Argus". 3 September 1875.

- http://www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au Supreme Court

- "HIS HONOR SIR REDMOND BARRY, KT., M.A., LL.D., &c." Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers (Melbourne) (National Library of Australia): p. 63. 29 February 1872. . Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- Blainey, Geoffrey, A Centenary History of the University of Melbourne. Carlton, Vic.; Melbourne University Press; 1957

- "SIR REDMOND BARRY, K.C.M.G., LL.D." The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 24 November 1880. p. 5. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- "Redmond Barry Professors". The University of Melbourne. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "Redmond Barry Award | Australian Library and Information Association". www.alia.org.au.

- Corfield, Justin The Ned Kelly Encyclopaedia (2003); Lothian Books; pg 158

- Corfield, Justin The Ned Kelly Encyclopaedia (2003); Lothian Books; pg 160

Sources

- Blainey, Geoffrey A Centenary History of the University of Melbourne. Carlton, Vic.; Melbourne University Press; 1957

- Corfield, Justin The Ned Kelly Encyclopaedia; Lothian Books; 2003

- Cowan, (Sir) Zelman The Redmond Barry Centenary Oration. Delivered at Wilson Hall, University of Melbourne; [Melbourne]; Royal Historical Society of Victoria; [1980]

- Galbally, Ann Redmond Barry: An Anglo-Irish Australian. Carlton, Vic.; Melbourne University Press; 1995

- Jones, David J. The Australian Librarian's Manual: Volume 3: Glossary. Sydney, Library Association of Australia 1985

- Kenneally, J. J. The Inner History of the Kelly Gang and their pursuers, (first printed 1929); (quote above from 1969 (8th) edition p. 188)

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Barry, Sir Redmond". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

- Ryan, Peter (1980). Redmond Barry: A Colonial Life 1813–1880 (Revised edition). Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0522842143. Small pamphlet.

Further reading

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Redmond Barry |

External links

- Supreme Court of Victoria Website

- Redmond Barry's Gravesite

- Peter Ryan, 'Barry, Sir Redmond (1813–1880)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 3, Melbourne University Press, 1969, pp 108–111.

- Redmond Barry Award, Australian Library and Information Association

| Victorian Legislative Council | ||

|---|---|---|

| New creation | Nominated Member & Solicitor-General July 1851 – June 1852 |

Succeeded by Edward Williams |

| Academic offices | ||

| New title | Chancellor of the University of Melbourne 1853 – 1880 |

Succeeded by Sir Anthony Brownless |