Lado Enclave

The Lado Enclave was an exclave of the Congo Free State and later of Belgian Congo that existed from 1894 until 1910, situated on the west bank of the Upper Nile in what is now South Sudan and northwest Uganda.

.jpg)

History

Traditionally the home of the Lugbara, Kakwa,[1] Bari,[2] and Moru peoples,[3] the area became part of the Ottoman-Egyptian province of Equatoria, and was first visited by Europeans in 1841/42, becoming an ivory and slave trading centre.[4] Lado, as part of the Bahr-el-Ghazal, came under the control of the British and in 1869 Sir Samuel Baker created an administration in the area, based in Gondokoro, suppressed the slave trade and opened up the area to commerce.[5]

Charles George Gordon succeeded Baker as Governor of Equatoria in 1874 and noting the unhealthy climate of Gondokoro, moved the administrative centre downstream to a spot he called Lado,[6] laying the town out in the pattern of an Indian cantonment, with short, wide and straight streets, and shady trees.[7] Gordon made the development of primary industry in Lado a priority, with the start of commercial farming of cotton, sesame and durra and the introduction of livestock farming.[8] Although Gordon stationed over three hundred soldiers throughout the region[9] his efforts to consolidate British control over area were unsuccessful and when he resigned as governor in 1876, only Lado and the few garrison settlements along the Nile could be considered administered.[10]

Emin Pasha was appointed as governor to replace Gordon and began to build up the region's defences and developed Lado into a modern town, founding a mosque, Koranic school and a hospital, so by 1881 Lado boasted a population of over 5000 tokuls (round mud huts common to the region).[11]

Russian explorer Wilhelm Junker arrived in the Lado area in 1884, fleeing the Mahdist uprising in the Sudan, and made it his base for his further explorations of the region.[12] Junker wrote complimentarily of Lado town, in particular its brick buildings and neat streets.[12]

During the Mahdist rule of the region, Lado was allowed to fall into disuse but Rejaf was made into a penal settlement.[13]

Belgian rule

British desire for a Cape to Cairo railway led them to negotiate with the Belgians to exchange the area that became the Lado Enclave for a narrow strip of territory in eastern Congo between Lakes Albert and Tanganyika. These negotiations resulted in the 1894 British-Congolese Treaty, signed on 12 May, under which the British leased all of the Nile basin south of the 10° north latitude to King Leopold II of the Belgians for the period of his lifetime.[3][14] This area, called the Lado Enclave, linked the Congo with the navigable Nile.[15]

The treaty also dictated that the whole of the Bahr-el-Ghazal (with the exception of the Lado Enclave) be ceded to the Congo State during the lifetime of King Leopold "and his successors." The British knew that Belgium would be unable to occupy Lado "for some time".[16]

French concern about Belgium's aspirations in Africa led to the 1894 Franco-Congolese Treaty, signed on 14 August, in which Leopold was forced to renounce all right to occupy north of the 5° 30" north latitude[17] in exchange for French acceptance of Leopold's ownership of Lado.[18] However, it was not until 1896 that Leopold had the resources to assemble an expedition to the enclave; "an expedition which was without doubt the greatest that nineteenth century Africa had ever seen", under Baron Dhanis.[3] The official plan was to occupy the enclave, but the ultimate aim was to use Lado as a springboard to capturing Khartoum to the north and control a strip of Africa from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean.[3] Dhanis' expedition mutinied in 1897.

Later in 1897, troops of the Congo Free State under Louis Napoléon Chaltin attempted to physically take control of the enclave.[19] Chaltin's forces reached the Nile at the town of Bedden in the enclave in February 1897 and defeated the Mahdists in the Battle of Rejaf.[20] This consolidated Léopold's claim to the Upper Nile, but although he had instructed Chaltin to continue on towards Khartoum, Chaltin did not have the forces to do so,[21] and instead chose to heavily fortify Lado (which had ceased to exist under the Mahdists),[22] Rejaf,[23] Kiro, Loka, and Yei, and occupied Dufile.[22]

By 1899, the British Government was claiming that the Congo State had not fulfilled its obligations of the Anglo-Congolese Treaty and therefore had no right to claim the Bahr-el-Ghazal. At the same time the Convention was signed, the Congo State forces had occupied Rejaf, and by a tacit understanding, the State was permitted to remain in occupation of the Lado Enclave. "The Bahr-el-Ghazal has never ceased to be British, and any extension of the sphere of influence of the Congo State beyond the limits of the Lado Enclave, with out the express sanction of the British Government is a wholly unjustifiable, and indeed, filibustering proceeding."[24]

In 1899, Leopold wanted to annul the Franco-Congolese Treaty, allowing him to gain more territory but the British opposed it, claiming that "serious consequences" would occur if Leopold attempted to expand the enclave's borders.[25]

In January 1900, some bored officials who had decided to explore the swamps beyond the Lado border were found by a British patrol. British officials believed this to be an official sortie and considered sending a military expedition to the enclave.[26]

Kiro had been the location of the British residence in the region but following the move to Belgian rule, a post (also called Kiro) was established a few kilometres north of the Lado Enclave's Kiro on the west bank of the Nile. However, in April 1901 it was discovered that this post lay within the enclave's territory and a new British post was created across the river at Mongalla.[27] The British were quick to populate and arm Mongalla, with a British Inspector, police officer, two companies of the Sudanese battalion under a British officer and a gunboat stationed there.[28]

In 1905, the strategic importance of the Lado Enclave became clear enough for the British to consider offering Leopold a small part of the Bahr-el-Ghazal in exchange for the enclave.[29] As part of this offer, the British agreed to remove their troops from the area while Leopold considered the offer. However, instead of considering, Leopold immediately ordered his troops to occupy the now vacant military posts, which was seen as a "futile and disastrous outbreak of Leopold's lust for short-term advantages. Its inevitable result was a sharp British order to Congolese forces to retreat southwards, followed by the closing of the Nile to Congolese transport."[30]

In May 1906 the British cancelled the Belgian lease of the Bahr-el-Ghazal, although Leopold refused to evacuate the region until the promised railway between the Lado Enclave and the Congo frontier was built.[31]

The Lado Enclave was important to the Congo Free State as it included Rejaf, which was the terminus for boats on the Nile, as the rapids there proved a barrier to further travel.[32] Rejaf was the seat of the commander, the only European colonial official within the enclave, who were in place from 1897 to June 1910. Efforts were made to properly defend Lado against any possible incursion by another colonial power, with twelve heavy Krupp fort guns installed in November 1906.[33]

However, there continued to be uncertainty in the enclave with the knowledge that the enclave would revert to British rule upon Leopold's death. As a result, the Belgians were unable to create an effective government, leading to civil unrest within the enclave.[34]

There were also rumours of gold deposits in Lado which led to great interest in the region in the early years of the twentieth century.[35]

Geography

The enclave had an area of about 15,000 square miles (39,000 km2), a population of about 250,000 and had its capital at the town of Lado which is near to the modern-day city of Juba. Under the 1894 Anglo-Congolese Treaty, the enclave's territory was dictated as "bounded by a line starting from a point situated on the west shore of Lake Albert, immediately to the south of Mahagi, to the nearest point of the frontier defined in paragraph (a) of the preceding Article. Thence it shall follow the watershed between the Congo and the Nile up to the 25th meridian east of Greenwich, and that meridian up to its intersection by the 10th parallel north, whence it shall run along that parallel directly to a point to be determined to the north of Fashoda. Thence it shall follow the thalweg of the Nile southward to Lake Albert, and the western shore of Lake Albert to the point above indicated south of Mahagi."[36]

A landlocked territory, it was bordered on the north by the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan province of Bahr-el-Ghazal[37] and on the east by the Nile. The shifting sandbanks of the Nile led to islands on the border of the enclave and the Sudan regularly created or destroyed and made navigability difficult.[38]

Described variously as "a small muddy triangle along the Nile, ... a chain of desolate mudforts"[39] and "shaped like a leg of mutton".[40]

Lado was the largest town in the enclave, while Yei, a fortified military station on the Yei River, was considered the second most important town.[22] The northernmost post was Kiro, on the west bank of the Nile nineteen kilometres above the British post at Mongalla.[28] English traveler Edward Fothergill visited the Sudan around 1901, basing himself at Mongalla between Lado to the south and Kiro to the north, but on the east shore of the river. By his account "Kiro, the most northern station of the Congo on the Nile, is very pretty and clean. Lado, the second station, is prettier still". However, he said that although the buildings were well made, they were too closely crowded together.[41]

While a large percentage of its population were Indigenous inhabitants, many Bari left the enclave, escaping Belgian rule, and settled on the eastern (Sudanese) shore of the Nile.[2]

The enclave was an area of seismological activity, particularly around Rejaf (which means "earthquake" in Arabic).[42] A fault line runs as a notable escarpment west of Rejaf south to Lake Albert, and while no major tremors occurred during the existence of the Lado Enclave, there was a noticeable earthquake in the region, centered on Rejaf, on 21 May 1914, which destroyed or damaged most of the buildings in the town.[42]

Fauna and flora

The enclave was well known for its enormous herds of elephants[43] which drew big-game hunters from around the world. From the years 1910 to 1912, hunters arrived in great numbers and shot thousands of elephants before Sudanese officials were able to take control of the area.[44] One of the most prolific was the Scottish adventurer W. D. M. Bell.

Hippopotami were described as having been "extremely numerous and particularly obtrusive" in the enclave but their presence had dropped to almost zero during the enclave's existence.[45]

In 1912, renowned naturalist Dr Edgar Alexander Mearns travelled through the enclave as part of his expedition through eastern Africa searching for new fauna, and reported a new subspecies of Temminck's courser within the enclave.[46]

Demographics

Health

Tsetse flies were common in the enclave and African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness), the medical condition that can occur as a result of a tsetse fly bite, led to a number of fatal cases recorded in the enclave.[47]

Malaria was the most common disease in the region, with about 80 per cent of the sickness in the neighboring Bahr El Ghazal due to malaria.[48] Those suffering from malaria also faced Blackwater fever,[49] whereby red blood cells burst in the bloodstream, releasing hemoglobin directly into the blood vessels and into the urine, frequently leading to kidney failure.

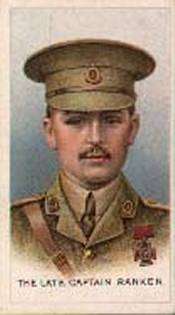

Captain Harry Ranken, who would in World War I be awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry, was posted to the enclave in 1911 and 1914 as a member of the Sudan Sleeping Sickness Commission, where he was based in Yei and researched methods of treatment for sleeping sickness and yaws.[50] He was due to return to the enclave in 1915 to complete his research but died from shrapnel wounds in France while serving on the front line.[50]

Weather

The seasons in the Lado Enclave were similar to neighboring regions of East Africa, whereby there were two seasons, with the dry season occurring from December to February and the wet season from March to November, although daily rain storms usually did not occur until June.[51]

The temperature was comparatively cool, and the temperature was said to "very seldom rise to 100° Fahrenheit".[51]

Economy

The economy of the Lado Enclave was based on ivory and rubber. As a small region, the enclave's trading ability was small, although a lively trading community of "Egyptians, Copts and Greeks" was recorded.[52] Cotton, alcohol and utensils were the most popular items traded into the enclave.[52]

Neither the Belgians nor the Sudanese introduced money taxation, preferring instead to collect grain and livestock as taxation.[53]

Incorporation into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

On 10 June 1910, following Leopold's death, the district officially became a province of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, with British Army veteran Captain Chauncey Hugh Stigand appointed administrator.[54] In 1912 the southern half of the Lado Enclave was ceded to Uganda, then a British protectorate. However, in reality, following Leopold's death and the subsequent withdrawal of Belgian troops, British authorities neglected to administer the area, leaving the enclave to become a "no man's land".[55] Ivory hunters moved in and shot almost all of an estimated herd of 2000 elephants resident in the enclave, netting the hunters large profits.[55]

In 1912 Captain Harry Kelly of the British Royal Engineers was sent to the region to adjust the Sudan-Uganda border,[56] with the plan to grant Uganda a southern part of the enclave, which Uganda could more easily administer, and in return to transfer part of northern Uganda to the Sudan, thereby placing all navigable parts of the Nile under Sudanese control.[56] This was achieved on 1 January 1914 when Sudan formally exchanged part of the enclave for a stretch of the Upper Nile.[57] The area of the Lado Enclave integrated into Uganda was renamed West Nile, best known as the ancestral home of Idi Amin.[58]

Later Gondokoro, Kiro, Lado and Rejaf were abandoned by the Sudanese government, and no longer appear on modern maps.[59]

The Lado Enclave in popular culture

Although the Lado Enclave was a small, remote area in central Africa, it captured the imagination of world leaders and authors, becoming a byword for an exotic region, and was used as a setting for their stories.

Winston Churchill travelled through the enclave, declaring it "present(ed) splendid and alluring panoramas".[60]

Lord Kitchener travelled to Lado for hunting, and shot a large white rhinoceros considered a "splendid trophy", with the horn being "some twenty seven inches long" and the rhinoceros standing six feet tall.[61]

Additionally, the Lado Enclave was also a popular attraction for the wealthy classes, with reports stating that "still more exhilarating was to be taken to the Lado Enclave, East Africa's equivalent to the badlands".[62]

The enclave was the site of "the last big elephant hunt on the continent",[63] as dozens of hunters from around the world converged on the enclave over the years 1907 to 1909, killing several thousand elephants.[63] The publicity from this hunt and the resulting public outrage led to the beginnings of the conservation movement.[63]

In his novel Elephant Song, Wilbur Smith refers to the slaughter of elephants in the Lado Enclave following the withdrawal of the Belgian colonial service in 1910,[64] Ernest Hemingway, in his novel True at First Light, references the enclave as a wild place[65] while the 1936 story "The Curse of Simba", refers to the enclave as the possible locale of the legendary Elephants' graveyard.[66]

Congo Free State and Belgian Commandants of the Enclave

| From | To | Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 February 1897 | November 1897 | Louis Napoléon Chaltin | |

| November 1897 | 15 December 1898 | Léon Charles Edouard Hanolet | |

| 15 December 1898 | 1 May 1900 | Jean Baptiste Josué Henry de la Lindi | |

| 1 May 1900 | March 1902 | Louis Napoléon Chaltin (Second time) | |

| December 1901 | August 1903 | Captain Léon Charles Edouard Hanolet (Second time)[22] | |

| January 1903 | 24 March 1904 | Commissaire General Georges François Wtterwulghe | Died at Yei on 8 May 1904.[22] |

| 24 March 1904 | 1904 | Commandant Florian Alexandre François Wacquez | Acting for Wtterwulghe to 8 May 1904.[22] |

| 1904 | May 1907 | Ferdinand, baron de Rennette de Villers-Perwin | Acting to August 1906 |

Commandants of the Lado Enclave:

- 1900 – January 1903: Gustave Ferdinand Joseph Renier (s.a.)

- January 1903 – August 1903: Albéric Constantin Édouard Bruneel

- August 1903 – March 1905: Henri Laurent Serexhe

- March 1905 – January 1908: Guillaume Léopold Olaerts

- January 1908 – April 1909: Léon Néstor Preud'homme

- April 1909 – 1910: Alexis Bertrand

- 1910 – June 1910: Charles Eugène Édouard de Meulenaer

See also

- Colonisation of the Congo

- Congo Crisis

- Belgian Colonial Empire

References

- Middleton, p. 11.

- Gleichen, p. 79.

- Stenger, p. 277.

- Canby, p. 497.

- "Sir Samuel White Baker" (2013) Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, 1.

- Middleton, pp. 169–170.

- Gray, p. 108.

- Cohen, p. 1660.

- Gleichen, p. 235.

- Flint, p. 143.

- Gray, pp. 140–141.

- Middleton, p. 300.

- Gleichen, p. 262.

- Taylor, p. 53.

- Pakenham, pp. 525-526.

- Emerson, p. 194.

- Ingham, p. 170.

- Collins, p. 193.

- Oliver & Sanderson, p. 331.

- Hill p. 99.

- Degefu, p. 39.

- Gleichen, p. 279.

- Pakenham, p. 527.

- "The Foreign Situation", The Advertiser (Adelaide), 11 November 1899, p. 9.

- Emerson, p. 198.

- Emerson, p. 199.

- Gleichen, p. 273.

- Gleichen, p. 153.

- Ascherson, p. 228.

- Ascherson, p. 230.

- The Age, "Congo Free State", 29 June 1906, p. 6.

- Hill, p. 330.

- "The Lado Enclave", The Mercury, 30 November 1906, p. 5.

- Christopher, p. 89.

- Wack, p. 291.

- Gleichen, p. 286.

- Gleichen, p. 1.

- Gleichen, p. 20.

- Pakenham, p. 451.

- Pakenham, p. 525.

- Edward Fothergill (1910). "Five years in the Sudan". Hurst & Blackett.

- Stigand (1916), p. 145.

- C.C. "Review: Big Game Hunting in Central Africa by W. Buckley", The Geographical Journal, vol. 77, no. 3, p. 275.

- C.C., p. 276.

- Gleichen, p. 80.

- "Recent Literature", The Auk, vol. 33, no. 1. (January 1916), American Ornithologists' Union. p. 89.

- Gleichen, p. 159.

- Gleichen, p. 157.

- Gleichen, p. 167.

- "The Late Captain R.S. Ranken, V.C.", The British Medical Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2815, 12 December 1914, p. 1049.

- Gleichen, p. 147.

- Gray, p. 140.

- Middleton, p. 16.

- Hill, p. 346.

- "Review of 'Big Game Hunting in Central Africa", The Geographical Journal, vol. 77, no. 3, March 1931, p. 276.

- Sharkey, R. "Book Reviews: Imperial boundary making: the diary of Captain Kelly and the Sudan-Uganda boundary commission of 1913, in International Journal of African Historical Studies, 1998, Vol. 31, Issue 2.

- Holt & Daly, p. 120.

- Decker, p. 23.

- W. Robert Foran (April 1958). "Edwardian Ivory Poachers over the Nile". African Affairs. 57 (227): 125–134. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a094547. JSTOR 719309.

- Churchill, p. 45.

- "The Jungle in London", The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 June 1914, p. 1.

- Lake, p. 66.

- Christopher, p. 90.

- Smith, p. 77.

- Hemingway, p. 15.

- "According to Bungo, there was supposed to be a corner of the Lado Enclave into which no white men had as yet penetrated; and, apart from the grave-yard business, the inhabitants were rumored to be a pretty queer race." "The Curse of Simba", the World's News, 15 July 1936, p. 24.

Sources

- Ascherson, N. (2001) The King Incorporated: Leopold II in the Age of Trusts, Granta Books. ISBN 1-86207-290-6.

- Canby, C. (1984) The Encyclopaedia of Historic Places, vol. 1., Mansell Publishing: London. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Churchill, W. (2015) My African Journey, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1515035985.

- Cohen, S. (1998) The Columbia Gazeeter of the World, Columbia University Press: New York. ISBN 0 231 11040 5.

- Collins, R.O. (1960) "The transfer of the Lado Enclave to the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1910", Zaïre: revue congolaise, Vol. 14, Issues 2–3.

- Decker, A.C. (2014) In Idi Amin’s Shadow : Women, Gender, and Militarism in Uganda, Ohio University Press: Athens, Ohio. ISBN 9780821445020.

- Emerson, B. (1979) Leopold II of the Belgians, Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London. ISBN 0 297 77569 3.

- Degefu, G.T. (2003) The Nile: Historical, Legal and Developmental Perspectives, Trafford Publishing: Victoria. ISBN 1-4120-0056-4.

- Flint, J.E. (ed.) (1976) The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 5. From 1790 to 1870, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 0521-20701-0.

- Gleichen, A.E.W. (ed.) (1905) The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A Compendium prepared by officers of the Sudan Government, Harbisons & Sons: London.

- Gray, R. (1961) A History of the Southern Sudan 1839-1889, Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Hemingway, E. (1999) True at First Light, Scribner: New York. ISBN 0 7432 4176 2.

- Hill, R.L. (1967) A Biographical Dictionary of the Sudan (2nd Edition), Frank Cass and Company, Ltd: London.

- Holt, P.M. & Daly, M.W. (1988) A History of the Sudan, 4th ed., Longman: London. ISBN 0 582 00406 3.

- Hochschild, A. (1999) King Leopold's Ghost, Mariner Books. ISBN 0-618-00190-5.

- Ingham, K. (1962) A History of East Africa, Longmans: London.

- Lake, M. (2006) Memory, monuments and museums, Melbourne University Press: Melbourne. ISBN 9 780 52285250 9.

- Middleton, J. (1971) "Colonial rule among the Lugbara" in Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1960, vol. 3., (ed. Turner, V.), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 0521-07844-X.

- Moorehead, A. (1960) The White Nile, Dell: New York.

- Oliver, R. & Sanderson, G.N. (1985) The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 6: From 1870 to 1960, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-228034.

- Pakenham, T. (1991) Scramble For Africa, Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-380-71999-1.

- Smith, W. (2011) Elephant Song, Pan Books: London. ISBN 978 0 330 46708 7.

- Stenger, S.J. (1969) "The Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo before 1910", in Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1960, vol. 1, (ed. Gavin, L.H. & Duignan, P.) Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-07373-1.

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1950) "Prelude to Fashoda: The Question of the Upper Nile, 1894-5", The English Historical Review, Vol. 65, No. 254, Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Wack, H.W. (1905) The Story of the Congo Free State: Social, Political, and Economic Aspects of the Belgian System of Government in Central Africa, G. P. Putnam's Sons: New York.

- WorldStatesmen: The Sudan