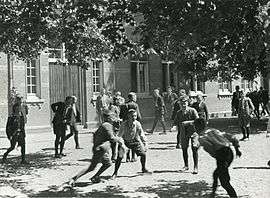

Recess (break)

Recess is a general term for a period in which a group of people are temporarily dismissed from their duties.

In education, recess is the American term (known as break or playtime in the UK), where students have a mid morning snack and play before having lunch after a few more lessons. Typically ten to thirty minutes, in elementary school[1] where students are allowed to leave the school's interior to enter its adjacent outside park where they play on equipment such as slides and swings, play basketball, tetherball, study or talk. Many middle and high schools also offer a recess to provide students with a sufficient opportunity to consume quick snacks, communicate with their peers, visit the restroom, study, and various other activities.

Importance of play in child development

During recess, children play, and learning through play has been long known as a vital aspect of childhood development.[2] Some of the earliest studies of play began with G. Stanley Hall, in the 1890s. These studies sparked an interest in the developmental, mental and behavioral tendencies of babies and children. Current research emphasizes recess as a place for children to “role-play essential social skills” and as an important time in the academic day that “counterbalances the sedentary life at school.”[3] Play has also been associated with the healthy development of parent-child bonds, establishing social, emotional and cognitive developmental achievements that assist them in relating with others, and managing stress.

Although no formal education exists during recess, sociologists and psychologists consider recess an integral portion of child development, to teach them the importance of social skills and physical education. Play is essential for children to develop not only their physical abilities, but also their intellectual, social, and moral capabilities.[4] Via play, children can learn about the world around them. Some of the known benefits of recess are that students are more on task during academic activities, have improved memory, are more focused, develop a greater number of neural connections, and that it leads to more physical activity outside of the school setting.[5] Psychomotor learning also gives children clues on how the world around them works as they can physically demonstrate such skills. Children need the freedom to play to learn skills necessary to become competent adults such as coping with stress and problem solving.[6] Through the means of caregiver's observations of children's play, one can identify deficiencies in children's development.[7] While there are many types of play children engage in that all contribute to development, it has been emphasized that free, spontaneous play—the kind that occurs on playgrounds—is the most beneficial type of play.

Recess is key in the development of children. Studies have shown that recess plays a large role in of how children develop their social skills. During recess, children usually play games involving teamwork. On the playground, children use many leadership skills – they educate other children about games to play, take turns, and learn to resolve conflicts while playing these games.[8] The leadership skills promoted throughout recess are how children are able to continue to play the games. Along with developing social skills, recess helps with the development of children's brains. Recess gives the children's brains a chance to “regroup” after a long day of class. Also, the physical activity actually leads to the development of the brain. Brain research has shown a relationship between physical activity and the development of the human brain.[9] Another study supports these findings from the brain research. A school system that dedicated one third of their school day to nonacademic activities such as recess, physical education, etc., led to improved attitudes and fitness, and improved test scores despite spending less time in the classroom.[9]

Social development

Problem solving is an integral part in child development and free play allows for children to learn to problem solve on their own. Teachers and caregivers can scaffold problem solving through modeling or assisting when a confrontation occurs. Although play should involve adults, adults or caregivers should not control the play because when adults control the play, the children can lose their creativity, leadership, and group skills. Adults should let children create and follow agreed upon rules and only intervene if a serious conflict arises.[10] Problem solving encourages children to compromise and cooperate with each other.[11] The conflict resolution process helps children to attain a vast range of social and emotional skills such as empathy, flexibility, self-awareness, and self-regulation. This vast range or capabilities is often referred to as "emotional intelligence" and is essential to building and maintaining relationships in adult life.[4] Teachers can also view recess as a time to observe children's social and cognitive development skills and be able to develop different activities in the classroom that reflect the children's interests and development.[12] Recess at its core is a social experience for children and as such, plays a significant part in the development of language. Children's intentionality with language during recess is tied closely to navigating the social landscape of the playground. Even as early as preschool, children use language to make group decisions and establish authority or a standing in the social setting of the playground. One researcher states that children use language to “invoke play ideas as their own possessions to manage and control the unfolding play,”[13] which engages a bidding war for group leadership. When viewing recess through a language perspective, the individual experience of the playground can vary depending on a willingness to follow other's ideas, and the development of language to modify play as it unfolds.

Indoor recess

Depending on the weather (rain, large amounts of snow, and sometimes in extreme heat), recess may be held indoors. Therefore should include creative activities that promote movement of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, whether in a gym or a classroom.[1] Allowing the students to finish work, play board games or other activities that take more than one to play; this helps encourage group activity and some games are also educational. Or, they might play educational computer games or read books. It also may contribute to do something non-educational, to help unwind and de-stress from the daily workload. Sometimes, some classes might watch a movie.

Recess data

The debate surrounding recess has been around for decades and is still happening today. Some people believe that recess is important, while others argue that eliminating recess will lead to better academic achievement.[14] Educators, parents, and experts are debating the importance of recess and play time in the school day.[15] Data shows that recess has many benefits for students.[16] These benefits include increased health, increased test scores, increased attention and social abilities, as well as better behavior. This is because during this physical activity, students produce dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in memory and problem-solving.[17][18] Also, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) advocates for unstructured play, including recess. NAEYC recommends play as a way for children to decrease stress and develop socially.[19] But, about 40% of school districts in the United States are doing away with recess.[20] Studies show that this lack of free and unstructured play during recess may contribute to the rise in childhood obesity, anxiety and depression among children, as well as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Childhood obesity and type 2 diabetes

Childhood obesity and type 2 diabetes are also a major concern as United States youth do not get the physical outlet needed not only for their cognitive development but for their physical health.[21] Statistics show that children are getting 50% less physical exploration and activity than decades before.[22] Research has shown that spending 60 minutes a day doing physical activity can prevent childhood obesity.[23] The U.S. Health and Human Services department also has a guideline for 60 minutes a day of physical activity.[24] But, research has shown that only very few children actually meet this national guideline.[25] Failure to meet this guideline and exercise daily is leading to harmful health issues for children.[26] Recess can be an outlet for students to get some of this physical activity and aid in preventing childhood obesity and diabetes.[14]

Timing of Recess

Another important aspect of recess to consider is what time of day it should be implemented. Traditionally schools have recess after lunch. But, in 2002, the Recess before Lunch (RBL) movement was founded. A health team in Montana created a study on four schools that made this schedule adjustment. After this study, many schools have started adapting the recess before lunch schedule.[27] Research suggests that having recess before lunch can improve the nutrition and behavior of elementary students.[28]

Effects on classroom behavior

According to the American Heart Association, the CDC reported that there is a link between physical activity and academic performance in 2010.[29] Some benefits to recess include students being more attentive, better academic performance and better behavior.[30] Many different studies show recess as being beneficial to students in the classroom. One of the goals of recess is to help students release excess energy and be refreshed focused upon return to the classroom.[31] According to a 2009 study, children who received daily recess were reported to behave better within the classroom.[32] After a long time in the classroom, students may become restless and disengaged. Studies show that after recess students become more attentive and engaged in classroom discussions.[33] This is because recess gave students a necessary break from the rigorous classroom and learning setting. A 2017 study of fifth graders suggested that 25 minutes of recess could increase students time on task.[34] Also, recess can reduce the risk of students falling asleep during learning time by its physical aspect allows students' bodies to oxygenate and stay awake.[35]

Restriction of recess as disciplinary action

In many schools around the country recess is taken away from students as disciplinary action. In 2013, researchers form the University of Chicago Illinois found that 68 percent of school districts had no policy or law prohibiting educators to take away physical activity from students.[36] Because of this, many educators and administrators take away recess as a punishment. A Gallup poll conducted in 2009 revealed that 77 percent of principals say that they have taken away recess from students.[37] Oftentimes students serve punishments such as completing late work or talking to the principal regarding behavioral issues during their recess times.[38] However, by taking away recess, student is unable to release the excess energy. Releasing this excess energy can lead to better behavior and academic performance.[39] Although taking away recess as disciplinary action seems to be the decision in many schools, researchers are coming up with alternatives for the elimination of recess.[40] Some of these alternatives include positive reinforcement which rewards children for positive behavior rather than taking away things for negative behavior. In this situation, every child is guaranteed recess.[41]

International recess

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, high school (11–16 or 18) students traditionally do not have 'free periods' but do have 'break' which normally occurs just after their second lesson of the day (normally referred to as second period). This generally lasts for around 20 minutes. During break, snacks are sometimes sold in the canteen (U.S. cafeteria) and students normally use this time to socialize or finish off any homework or schoolwork that needs to be completed. Once break is finished, students go to their next class. Lunchtime commences one or two lessons later and usually lasts around 45–60 minutes. This system is more or less the same in junior schools (7–11) in the UK and Ireland and in high schools (14–18) in the U.S., but infant schools (4 or 5–7) normally add another break time towards the end of the day.

In Australia, New Zealand, and Canada "recess" or playlunch is generally a break between morning and mid-morning classes. It is followed after mid-morning classes by a more lengthy break, lunchtime. Thus, the structure of the school-day consists of three lesson blocks, broken up by two intervals: recess and lunch respectively. There must be at least an hours worth of "recess" or "free period" a week.

The average school day in Japan is eight hours but the time in the classroom is no different compared to the U.S.: time spent out of the classroom is what makes the day longer. A quarter of the day is spent in non-academic activities. A typical day contains the same amount of instructional time as children in the U.S. but a long enough lunch break to go home and eat with their family. This gives the students time to soak in their morning lesson and prepare for the afternoon session. Students who do not go home read for their pleasure or interact with other students. When the school day is over the majority of the students do not go home, but rather stay after school for clubs and other activities. The benefits of having a longer break and several non-academic clubs after school is that the students interact with one another and tend to have fewer physical symptoms related to stress, as well as better relationships with their classmates.

Some schools in Beijing, China allow children to spend an hour or two to socialize or to step out of the classroom per day. Some schools do not have a dedicated recess period, instead allowing a ten-minute break per class session. For lunch, students either pack or buy from the school's lunch area. After lunch time there is a quiet period. During this period, children may read at their desks or play by themselves. Meanwhile, a few students are chosen to help clean up from lunch, which may be perceived as a coveted assignment. Schools implementing a no-recess policy may not even have a playground, while schools allowing recess may have multiple playgrounds or basketball courts.

Finnish students rank near the top in terms of academic testing and knowledge, and there students receive over an hour of recess everyday, regardless of the weather. In Finland schools consider recess to be an essential part of the school day, and this element of their curriculum is attracting international attention.

In Spain, all primary, middle and high schools allow a recess time for its students.

In Wales, pupils are expected to do only one hour of PE per fourteen days.[42]

United States

In the United States, recess policies are largely dependent on the school district, and vary from state to state and from school to school.[43] Most states do not have a recess policy. However, it is recommended that schools provide 150 minutes per week for physical activity in elementary schools and 225 minutes per week in middle and high school.[44] The point where recess ends in a child's education is largely dependent on the school district, though by many standards it is removed when the child enters middle school. However, in college, students usually have free periods, which are similar in spirit, although usually one studies or talks with one's friends during such times rather than playing games, which are made difficult by the lack of a playground.

Common recess activities

Recess is a common part of the school day for children around the world, but it has not received much attention from scholars. The research that has been conducted occurred mostly in the United States and the UK.[45] Of the fifty states in the United States, only fifteen have policies that recommend or require daily recess or a physical activity break, and one (Oklahoma) has no policy, but it is recommended by the State Board of Education.[46]

Certain activities have emerged as playground favorites, including: jump rope, Chinese jump rope, four square, hop scotch, basketball, soccer, hula hoops, chase, wall ball, and playing on the playground equipment.[47] These activities have been classified into chase games, ball games, and jumping/verbal games.[48] Other categories to consider would be general play and equipment related play.

- Chase games: tag, chase, hide and go seek

- Ball games: four square, basketball, wall ball, soccer, kick ball

- Jumping/verbal games: jump rope, Chinese jump rope, hop scotch, hula hoops, chanting/clapping/rhyming games, Duck Duck Goose

- General play: make believe or fantasy play, solitary play

- Equipment related play: swings, slides, climbing, monkey bars, tetherball

Games and play both occur on playgrounds, so it is important to differentiate between the two when discussing activities in which children engage at recess. One way to view their uniqueness is to look at the function of their rules. Games, such as basketball, have concrete rules that result in penalties when broken. Play rules, on the other hand, are flexible and can change at the discretion of the players.[48] There are times though when kids will bend the concrete rules of some games to make new versions of these games that may or may not be remembered in future times of play.

Recess activities run the gamut from simple to complex. Children's gender and age affects their recess recreation choices.[48] The youngest children in elementary schools (kindergarten through second grade) prefer the simplest activities such as chase, kickball, jump rope, and unstructured games. As the school year progresses, it has been observed that chase games diminish and ball games increase.[48] By the time children are in upper elementary school (grades three through five), they prefer sports and social sedentary behavior like talking.

Parliamentary procedure

In parliamentary procedure, a recess refers to a short intermission in a meeting of a deliberative assembly. The members may leave the meeting room, but are expected to remain nearby. A recess may be simply to allow a break (e.g. for lunch) or it may be related to the meeting (e.g. to allow time for vote-counting).

| Class | Privileged motion |

|---|---|

| In order when another has the floor? | No |

| Requires second? | Yes |

| Debatable? | No |

| May be reconsidered? | No |

| Amendable? | Yes |

| Vote required | Majority |

Sometimes the line between a recess and an adjournment can be fine.[49] A break for lunch can be more in the nature of a recess or an adjournment depending on the time and the extent of dispersion of the members required for them to be served.[49] But at the resumption of business after a recess, there are never any "opening" proceedings such as reading of minutes; business picks up right where it left off.[49] The distinction of whether the assembly recesses or adjourns has implications related to the admissibility of a motion to reconsider and enter on the minutes and the renewability of the motion to suspend the rules.[49]

Under Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised, a motion to recess may not be called when another person has the floor, is not reconsiderable, and requires a second and a majority vote.[50] When adopted, it has immediate effect.

If made when business is pending, it is an undebatable, privileged motion.[50] It can be modified only by amendment of the length of the break.[50]

Stand at ease

Stand at ease is a brief pause without a recess in which the members remain in place but may converse while waiting for the meeting to resume.[51]

Brazil

In the National Congress of Brazil, a recess is a break in congressional activities. During every year-long session, the congress has two scheduled recess periods: a mid-winter break between 17 July and 1 August, and a summer break between 22 December and 2 February of the following year.[52][53]

United States Congress

In the United States Congress, a recess could mean a temporary interruption or it could mean a longer break, such as one for the holidays or for the summer.[54][55]

References

- Tran, Irene; Clark, B. Ruth; Racette, Susan B. (November 21, 2013). "Physical Activity During Recess Outdoors and Indoors Among Urban Public School Students, St. Louis, Missouri, 2010–2011". Preventing Chronic Disease. 10: E196. doi:10.5888/pcd10.130135. ISSN 1545-1151. PMC 3839587. PMID 24262028.

- Honeyford, Michelle A.; Boyd, Karen (April 14, 2015). "Learning Through Play". Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 59 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1002/jaal.428. ISSN 1081-3004.

- Ramsetter, Catherine; Robert Murray; Andrew S. Garner (2010). "The Crucial Role Of Recess In Schools". Journal of School Health. 80 (11): 517–26. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00537.x. PMID 21039550.

- Gray, Peter (November 19, 2008). "The Value of Play 1: The Definition of Play Provides Clues to its Purpose". Psychologytoday.com.

- Adams, Caralee. "Recess Makes Kids Smarter". Scholastic Instructor. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- Trickey, Helyn (August 22, 2006). "No Child Left out of the Dodgeball Game?". Articles.cnn.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- How much do we know about the importance of play in child development? Tsao, Ling-Ling. Childhood Education. Olney. Summer 2002. Vol. 78, Iss. 4; Pg 230

- "10 Things Every Parent Should Know About Play | NAEYC". www.naeyc.org. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- Jarrett, O., Waite-Stupiansky, S. (September 2009). Play, Policy, and Practice Interest Forum.

- Ginsburg, Kenneth R. (January 1, 2007). "The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds". Pediatrics. 119 (1): 182–191. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2697. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 17200287.

- Walker, Olga L.; Degnan, Kathryn A.; Fox, Nathan A.; Henderson, Heather A. (2013). "Social Problem-Solving in Early Childhood: Developmental Change and the Influence of Shyness". Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 34 (4): 185–193. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2013.04.001. ISSN 0193-3973. PMC 3768023. PMID 24039325.

- "Developmental Play At School: Fun And Essential For Learning!". Child Development Institute. April 28, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- Theobald, Maryanne (2013). "Ideas As "Possessitives": Claims And Counter Claims In A Playground Dispute" (PDF). Journal of Pragmatics. 45 (1): 1. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.09.009.

- Ramstetter, Catherine L.; Murray, Robert; Garner, Andrew S. (October 7, 2010). "The Crucial Role of Recess in Schools". Journal of School Health. 80 (11): 517–526. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00537.x. ISSN 0022-4391. PMID 21039550.

- Pellegrini, Anthony (Fall 2008). "The Recess Debate: A Disjuncture between Educational Policy and Scientific Research" (PDF). American Journal of Play: 181–190.

- Jarret, Olga (November 2013). "A Research-Based Case for Recess" (PDF). US Play Coalition: 1–5.

- "Exercise, Depression, and the Brain". Healthline. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Shohamy, Daphna; Adcock, R. Alison (2010). "Dopamine and adaptive memory". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 14 (10): 464–472. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.5641. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.08.002. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 20829095.

- "10 Things Every Parent Should Know About Play | NAEYC". www.naeyc.org. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "IPA/USA : Promoting Recess". www.ipausa.org. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Recess-It's Indispensable! Young Children. National Association for the Education of young children. September 2009 Vol. 64, No. 5; pg. 66.

- "The Loss of Children's Play: A Public Health Issue" (PDF). Alliance for Childhood. November 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- "Recess a crucial part of school day, says American Academy of Pediatrics". Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- (ASH), President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition, Assistant Secretary for Health (July 20, 2012). "Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans". HHS.gov. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Few children get 60 minutes of vigorous physical activity daily". Tufts Now. April 5, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Beck, Erin. "Lack of Exercise for Children". LIVESTRONG.COM. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Recess Before Lunch". NEA. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Benefits of Recess Before Lunch" (PDF). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Status of Physical Education in the USA" (PDF). 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Jarrett, Olga S.; Maxwell, Darlene M.; Dickerson, Carrie; Hoge, Pamela; Davies, Gwen; Yetley, Amy (1998). "Impact of Recess on Classroom Behavior: Group Effects and Individual Differences". The Journal of Educational Research. 92 (2): 121–126. doi:10.1080/00220679809597584. ISSN 0022-0671.

- University, Stanford (February 11, 2015). "School recess offers benefits to student well-being, Stanford educator reports". Stanford News. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Baros, Romina; Silver, Ellen; Stein, Ruth (February 2009). "School Recess and Group Classroom Behavior" (PDF). Peadiactics. 123: 431–435.

- Singer, Dorothy; Golinkoff, Roberta Michnick; Hirsh-Pasek, Kathy (August 24, 2006). Play = Learning: How Play Motivates and Enhances Children's Cognitive and Social-Emotional Growth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198041429.

- Smith, Jenny (May 2017). "THE EFFECT OF RECESS ON FIFTH GRADE STUDENTS' TIME ON-TASK IN AN ELEMENTARY CLASSROOM" (PDF). The University of Mississippi.

- Hinson, Dr. Curt. "What is recess? – Playfit Education". www.playfiteducation.com. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Chriqui, Jamie; Resnick, Elissa; Chaloupka, Frank (February 2013). "School District Wellness Policies: Evaluating Progress and Potential for Improving Children's Health Five Years after the Federal Mandate" (PDF). Bridging the Gap.

- "The State of Play" (PDF). Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: 9. 2009.

- "Educators debate taking away recess". Chalkbeat. March 18, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Educators debate taking away recess". Chalkbeat. March 18, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Positive Discipline: 10 Ways to Stop Taking Recess Away – The Inspired Treehouse". The Inspired Treehouse. September 23, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Cordell, Sigrid Anderson (October 23, 2013). "Nixing Recess: The Silly, Alarmingly Popular Way to Punish Kids". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Physical education#cite note-20

- "The Crucial Role of Recess in Schools". ResearchGate. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- "Physical Education Guidelines". Shape America Society of Health and Physical Educators. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Holmes, Robyn M. (Winter 2012). "The Outdoor Recess Activities of Children at an Urban School: Longitudinal and Intraperiod Patterns". American Journal of Play. 4 (3): 327–351.

- "Recess Facts". April 23, 2012.

- Sinclair, Christina D.; Stellino, Megan Babkes; Partridge, Julie A. (2008). "Recess Activities of the Week (RAW): Promoting Free Time Physical Activity to Combat Childhood Obesity". Strategies: A Journal for Physical and Sport Educators. 21 (5): 21–24. doi:10.1080/08924562.2008.10590788.

- Pellegrini, Anthony D.; Blatchford, Peter; Kato, Kentaro; Baines, Ed (February 2004). "A Short-term Longitudinal Study of Children's Playground Games in Primary School: Implications for Adjustment to School and Social Adjustment to School and Social Adjustment in the USA and the UK". Social Development. 13 (1): 107–123. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00259.x.

- Robert, Henry M.; et al. (2011). Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised (11th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-306-82020-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robert 2011, p. 231

- Robert 2011, p. 82

- "Brazil - The legislature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "The National Congress". Portal da Câmara dos Deputados (in Portuguese). Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "recess glossary term". Senate.gov. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- Bolton, Alexander (August 3, 2014). "Five things to know as Congress takes a five-week summer recess". TheHill. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

External links