Ransom of King John II of France

The ransom of King John II of France was an incident during the Hundred Years War between France and England. Following the English capture of the French king during the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, John was held for ransom by the English crown. The incident had serious consequences for later events in the Hundred Years War.

Background

By the time of his capture in 1356, King John II's reign had been marked by tensions both within his kingdom and without. John's Valois claim on French territories was disputed by both Charles II of Navarre and Edward III of England. Vital provinces such as Normandy maintained a high level of autonomy from the crown and frequently threatened to disintegrate into private wars.[1] Worse, many nobles had closer links to the English crown than to Paris. The Hundred Years' War that had begun nineteen years before was not a modern war of nations; as one scholar has put it, it was 'an intermittent struggle... a coalition war, with the English often supported by Burgundians and Gascons, and even a civil war, whose combatants looked back to a heritage that was partly shared.'[2]

The French defeat at Crecy under John's father, Philip VI of France and the loss of Calais had increased the pressures on the Valois family to achieve military success. John himself was an unlikely candidate as a warrior prince. John suffered from fragile health and engaged little in physical activity, practiced jousting rarely, and only occasionally hunted. He enjoyed literature, and was patron to painters and musicians. Potentially in response to this, John had created the Order of the Star; like Edward III and the creation of the Order of the Garter, John hoped to play on the concepts of knightly chivalry to bolster his prestige and authority. John had grown up amongst intrigue and treason, and in consequence he governed in secrecy only with a close circle of trusted advisers, frequently alienating his nobles through what they perceived as arbitrary justice and the elevation of unworthy associates, such as Charles de la Cerda.[3] The issues of friction within the French nobility, weaknesses in personal administration and chivalric ideals would play out in the ransom of King John.

Capture

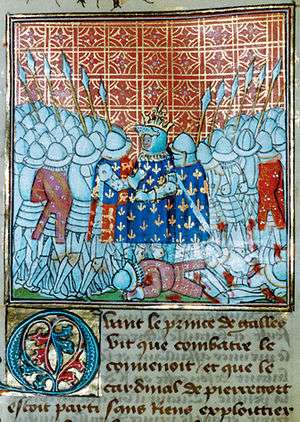

After a three-year break, the war resumed in 1355, with Edward, The Black Prince, leading an English-Gascon army in a violent raid, termed a chevauchée, across southwestern France. After checking an English incursion into Normandy, John led an army of about 16,000 south, crossing the Loire in September, 1356, attempting to outflank the Prince's 8,000 soldiers at Poitiers. The Prince's situation was poor; his forces were now trapped, outnumbered and weak from illness. John was confident of victory and, rejecting both the Prince's efforts to negotiate a solution, insisting on the Prince's surrender as a hostage, and advice from one captain to surround and starve the Prince, the King ordered a direct attack. In an era in which chivalry placed high importance on winning renown through personal feats of arms, or 'prowess',[4] and in which victory was a sign of God's favour, the prospect of a decisive battle must have been politically appealing to the troubled King.

The Battle of Poitiers was a disaster for the French. As at the Battle of Agincourt sixty years later, many French forces did not fully participate. Prominently, Dauphin Charles and his younger brother Louis left the battle early, possibly as a result of an order from John. At least their departure meant that they avoided capture by the English; King John was less fortunate. John had taken precautions against his own capture; he was guarded in the battle by the ninety members of the Order of the Star, and had nineteen knights from his personal guard dressed identically to confuse the enemy. Surrounded and with most of the Order dead, the King fought on with considerable personal valour until Denis de Morbecque, a French exile who fought for England, approached him.

"Sire," Morbecque is said to have announced, "I am a knight of Artois. Yield yourself to me and I will lead you to the Prince of Wales."

King John is said to have surrendered by handing him his glove. That night King John dined in the red silk tent of his enemy, where the Black Prince attended to him personally. He was then taken to Bordeaux, and ultimately from there to England, where he was at first held in the Savoy Palace, then at a variety of locations, including Windsor, Hertford, Somerton Castle in Lincolnshire, Berkhamsted Castle in Hertfordshire and briefly at King John's Lodge in East Sussex.[5] Eventually, John was taken to the Tower of London. As a prisoner of the English for several years, John was granted royal privileges, permitting him to travel about and to enjoy a regal lifestyle. His account books during his captivity show that he was purchasing horses, pets, and clothes while maintaining an astrologer and a court band.[6] Philip, John's fourth son, had also been captured at Poitiers and followed him into captivity.

Ransom

Now in English captivity, King John began the challenging task of negotiating a peace treaty, which would likely require the payment of a large ransom and territorial concessions. Meanwhile, in Paris, the Dauphin, Prince Charles, was facing his own difficulties in his new position as regent. Charles had returned to Paris with his honour intact, but popular feelings over a second French military disaster were running high. Charles summoned the Estates-General in October to seek money for the defense of the country, but furious at what they saw as poor and secretive management under King John, many of those assembled organized into a body led by Etienne Marcel, the Provost of Merchants. Marcel demanded widespread political concessions – Charles refused the demands, dismissed the Estates-General and left Paris.

Political strife ensued. In an attempt to raise money, Charles tried to devalue the currency; Marcel ordered strikes, and the Dauphin was forced to cancel his plans and recall the Estates in February, 1357. The Third Estate – the townsfolk – with support from many nobles, presented the Dauphin with a Grand Ordinance, a list of 61 articles that would have severely restricted royal powers. Under pressure from the mob, Charles eventually signed the ordinance as Regent, but when news of the document reached King John, still at this point imprisoned in Bordeaux, he immediately renounced the ordinance. During the summer, Charles began to successfully enlist support from the provinces against Marcel and the Parisian mob, successfully breaking back into Paris. The final act of violence was the murder by the mob of key royal officials; Charles fled the capital, but the attack broke the temporary alliance between townsfolk and nobility. By August 1358, Marcel was dead and Charles was, once more, able to return to his capital.

Back in England, King John signed a treaty in 1359 that would have ceded most of western France to England and involved a colossal ransom of 4 million écus for his freedom. Charles had little choice but to reject the treaty as invalid, and King Edward used this as an excuse to reinvade France later that year. Edward reached Reims in December and Paris in March, but Charles, trusting on the improved defences around Paris, refused to give battle. Edward pillaged and raided the countryside but could not bring the French to a decisive battle, and eventually agreed to reduce his terms. The Treaty of Brétigny, signed on 8 May 1360, ceded a third of western France – mostly in Aquitaine and Gascony — to the English, and lowered the King's ransom to a still-enormous 3 million crowns.

John's return

The Treaty of Brétigny, signed on 25 May 1360, offered the release of John in exchange for eighty-three hostages,[7] along with other payments. After four years in captivity, King John was released after the signing of the treaty. John's son, Prince Louis, who had avoided capture at Poitiers, was among the persons who were to be given as hostages. In October 1360, Louis sailed to England from Calais. The full ransom was to be paid within six months, but France was economically weakened and incapable of paying the ransom on schedule. After several years in captivity, Louis tried to privately negotiate with Edward III of England for his freedom. When this failed, Louis decided to escape; he arrived back in France in July 1363.

King John had returned to a difficult situation in 1360. France was still divided, had lost considerable territories, and was heavily indebted to England. The Dauphin's infant daughters, Joan and Bonne, died within two weeks of each other. Charles himself had been severely ill, with his hair and nails falling out; based upon the symptoms, some suggest that he had arsenic poisoning. Most of his inner circle had died at the Battle of Poitiers.

The royal administration continued to perform poorly. When John was informed that Louis had escaped, he voluntarily returned to captivity in England. John's council tried to dissuade him from doing so, but he persisted, citing "good faith and honor." He sailed to England that winter, and was warmly welcomed in London in January 1364. However, John became ill and died in April 1364. His body was returned to France, where he was interred in the royal chambers at Saint Denis Basilica.

It is not certain why John returned to captivity, even though chivalry was perhaps at its height at that time. Acts of mercy and clemency were looked upon positively in medieval times, but behaviour that violated the chivalric code was usually forgotten if it was clearly in the interests of the state. Escaping from captivity was unchivalrous, and carried consequences, but was still common nonetheless. John's critics alleged that he returned to London for "causa joci" (reasons of pleasure), citing his unmartial lifestyle. Historians have speculated that John simply could not face the difficulties of ruling France. John may have seen his failures and Charles' misfortunes as a sign from God, and consequently sought religious redemption. John may also have hoped to negotiate with Edward III directly.

Over time, the ransom of King John had a considerable impact. The money paid to England contributed to the royal treasury until the reign of King Henry V. Although the short reign of King Charles V was successful, the political unrest that ensued after the capture of King John fed into the instability of King Charles VI's reign, weakening France throughout much of the Hundred Years War.

References

- Françoise Autrand, Charles V, Fayard 1994

- Holmes, Richard 'War Walks from Agincourt to Normandy', p.17.

- Some historians, for example J. Deviosse, Jean Le Bon, Paris, 1985, also suggest a strong romantic and possibly homosexual attachment to Charles de la Cerda.

- Hibbert, Christopher, Agincourt, 1964, p.13.

- http://www.britannia.com/history/berks/windsor.html.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1978). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. Ballantine Books. pp. 168–169. ISBN 0-345-34957-1.

- Kosto, Adam J. (2012). Hostages in the Middle Ages. OUP Oxford. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-19-965170-2.