Ranjitsinhji

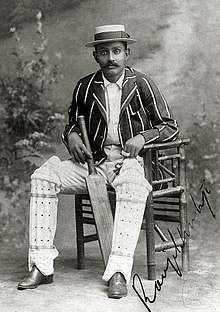

Sir Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji Jadeja, GCSI GBE (10 September 1872 – 2 April 1933[1]),[note 1] often known as Ranji, was the ruler of the Indian princely state of Nawanagar from 1907 to 1933, as Maharaja Jam Saheb,[3] and a noted Test cricketer who played for the English cricket team.[4] He also played first-class cricket for Cambridge University, and county cricket for Sussex.

| Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jam Saheb of Nawanagar (more) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maharaja of Nawanagar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1907–1933 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Jashwantsinhji Vibhaji II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 10 September 1872 Sadodar, Kathiawar, British India | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2 April 1933 (aged 60) Jamnagar Palace, Nawanagar State, British India | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Ranji, Smith | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right arm slow | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Batsman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 105) | 16 July 1896 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 24 July 1902 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1895–1920 | Sussex | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1901–1904 | London County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1893–1894 | Cambridge University | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Cricinfo, 2 April 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Cambridge University | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ranji has widely been regarded as one of the greatest batsmen of all time.[5] Neville Cardus described him as "the Midsummer night's dream of cricket". Unorthodox in technique and with fast reactions, he brought a new style to batting and revolutionised the game.[6] Previously, batsmen had generally pushed forward; Ranji took advantage of the improving quality of pitches in his era and played more on the back foot, both in defence and attack. He is particularly associated with one shot, the leg glance, which he invented or popularised. The first-class cricket tournament in India, the Ranji Trophy, was named in his honour and inaugurated in 1935 by the Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala. His nephew Duleepsinhji followed Ranji's path as a batsman playing first-class cricket in England and for the England cricket team.[2]

Away from cricket, Ranji became Maharaja Jam Saheb of Nawanagar in 1907. He was later Chancellor of the Indian Chamber of Princes, and represented India at the League of Nations. His official title was Colonel H. H. Shri Sir Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji II, Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, GCSI, GBE.

Early life

Birth

Ranjitsinhji was born on 10 September 1872 in Sadodar, a village in the state of Nawanagar in the western Indian province of Kathiawar. Born in a Yaduvanshi Rajput family,[7] he was the first son of a farmer, Jiwansinhji, and one of his wives.[8][9] His name meant "the lion who conquers in battle", although he frequently suffered ill health as a child.[8] Ranjitsinhji's family were related to the ruling family of the state of Nawanagar through his grandfather, and head of his family, Jhalamsinhji. The latter was a cousin of Vibhaji, the Jam Sahib of Nawanagar; Ranjitsinhji's biographers later claimed that Jhalamsinhji had shown bravery fighting for Vibhaji in a successful battle,[10] but Simon Wilde suggests that this may be an invention encouraged by Ranjitsinhji.[11][11][12] For the remainder of his life, Ranjitsinhji was sensitive about his family and deliberately presented a positive image of his parents.[11]

Heir to the throne

In 1856, Vibhaji's son, Kalubha, was born, becoming heir to Vibhaji's throne. However, as Kalubha grew, he established a reputation for violence and terror. Among his actions were an attempt to poison his father and a multiple rape.[13][14] Consequently, Vibhaji disinherited his son in 1877 and, having no other suitable heir, followed custom by adopting an heir from another branch of his family, that of Jhalamsinhji. The first selected heir died within six months of being adopted,[12] either through fever or poisoning on the orders of Kalubha's mother.[12][14] The second choice, in October 1878, was Ranjitsinhji. Vibhaji took him to Rajkot to secure the approval of the ruling British and the young boy lived there for the next 18 months before joining the Rajkumar College, supported through this time by an allowance from Vibhaji.[15] Being discouraged by the ambition of Ranjitsinhji's family and the conduct of Jiwansinhji, Vibhaji never completed the adoption of Ranjitsinhji and continued trying to produce his own heir.[16] The prospect of Ranjitsinhji's accession seemed to vanish in August 1882 when one of the women of Vibhaji's court gave birth to a son, Jaswantsinhji.[17]

Ranjitisinhji’s later version of events, reported by his biographer Roland Wild, was that his adoption had been carried out in secret, for fear of Vibhaji's wives. According to Wild, "The boy's father and grandfather watched the ceremony which was officially recorded by the India Office, the Government of India, and the Bombay Government."[14][18] However, there is no record of any such event, which Simon Wilde says, "suggests, fairly conclusively, it never happened."[18] Roland Wild and Charles Kincaid, who wrote a book in 1931 which also put forward Ranjitsinhji's perspective, also said that Jaswantsinhji was not a legitimate heir, either through not being Vibhaji's son or through his mother not being legally married to Vibhaji.[note 2] However, the claims are either demonstrably wrong or not corroborated by the records.[19]

The British authorities, unhappy to discover Ranjitsinhji was never adopted and impressed by his potential at the college, initially tried to persuade Vibhaji to retain Ranjitsinhji as his heir but the Jam Sahib insisted Jaswantsinhji should succeed him. In October 1884, the Government of India recognised Jaswantsinhji as Vibhaji's heir, but the Viceroy, Lord Ripon, believed that Ranjitsinhji should be compensated for losing his position.[20]

Education

Even though Ranjitsinhji was no longer heir, Vibhaji increased his financial allowance but passed the responsibility for his education to the Bombay Presidency. With his fees coming from the allowance, Ranjitsinhji continued his education at the Rajkumar College. Although his material position remained unchanged, comments made at the time by the principal of the college, Chester Macnaghten, suggest that Ranjitsinhji was bitterly disappointed by his disinheritance.[21] The college was organised and run like an English public school and Ranjitsinhji began to excel.[9]

First introduced to cricket aged 10 or 11, Rajitsinhji first represented the school in 1883 and was appointed captain in 1884; he maintained this position until 1888.[22] While he may have scored centuries for the school, the cricket was not of a particularly high standard, and very different from that played in England.[note 3] Ranjitsinhji did not take it particularly seriously and preferred tennis at the time.[22][23] No one was certain what would become of him once he left the college, but his academic prowess presented the solution of moving to England to study at Cambridge University.[24]

Cambridge University

Academic progress

In March 1888, Macnaghten took Ranjitsinhji to London, with two other students who exhibited potential. One of the events to which Macnaghten took Ranjitsinhji was a cricket match between Surrey County Cricket Club and the touring Australian team. Ranjitsinhji was enthralled by the standard of cricket, and Charles Turner, an Australian known more as a bowler, scored a century in front of a large crowd; Ranjitsinhji later said he did not see a better innings for ten years.[25] Macnaghten returned to India that September but arranged for Ranjitsinhji and one of the other students, Ramsinhji, to live in Cambridge. Their second choice of lodgings proved successful, living with the family of Reverend Louis Borrisow, at the time the chaplain of Trinity College, Cambridge, who tutored them for the next year. Ranjitsinhji lived with the Borrisows until 1892 and remained close to them throughout his life.[26] According to Roland Wild, Borrisow believed Ranji was "lazy and irresponsible"[27] and obsessed with leisure activities including cricket, tennis, billiards and photography.[28] Wild also says that he might have struggled to acclimatise to English life and did not settle to academic study.[27] Possibly as a consequence, Ranjitsinhji failed the preliminary entrance exam to Trinity College in 1889, but he and Ramsinhji were allowed to enter the college as "youths of position". Nevertheless, Ranjitsinhji concentrated more on sport than study while at Cambridge, being content to work no more than necessary and he never graduated.[29]

During the summer of 1890, Ranjitsinhji and Ramsinhji took a holiday in Bournemouth. For the trip, Ranji adopted the name "K. S. [Kumar Sri] Ranjitsinhji". While in Bournemouth, he took more interest in cricket, achieving success in local matches which suggested he possessed talent, but little refinement of technique. According to Wilde, by the time he returned to Trinity in September 1890, he was beginning to realise the benefit of others believing him to be a person of importance, something that was to lead to him adopting the title "Prince Ranjitsinhji", although he had no right to call himself a "Prince". Significantly, the trip planted the seed in his mind that he might find success as a cricketer.[30]

In June 1892, Ranjitsinhji left the Borrisow home and, with monetary assistance from relations,[31] moved into his own rooms in the city of Cambridge. He lived in luxury and frequently entertained guests lavishly.[32] According to writer Alan Ross, Ranjitsinhji may have been lonely in his first years at Cambridge and probably encountered racism and prejudice. Ross believes that his generosity may have partly arisen from trying to overcome these barriers.[29] However, Ranjitsinhji increasingly lived beyond his means to the point where he experienced financial difficulty. He intended to pass the examinations to be called to the Bar and wrote to ask Vibhaji to provide more money to cover the costs; Vibhaji sent the money on the condition Ranjitsinhji returned to India once he passed the examination.[32] Ranjitsinhji intended to keep to this arrangement, although he did not plan a career as a barrister, but his debts were larger than he had thought and not only could he not afford the cost of the Bar examination, he was forced to leave Cambridge University, without graduating, in spring 1894.[33]

Beginnings as a cricketer

At first, Ranjitsinhji had hoped to be awarded a Blue at tennis, but, possibly inspired by his visit to see the Australians play in 1888, he decided to concentrate on cricket. In 1889 and 1890, he played local cricket of a low standard,[34] but following his stay in Bournemouth, he set out to improve his cricket.[35] In June 1891 he joined the recently re-formed Cambridgeshire County Cricket Club and was successful enough in trial matches to represent the county in several games that September. His highest score was just 23 not out,[36][37] but he was selected for a South of England team to play a local side—which had 19 players to make the match more competitive—and his score of 34 was the highest in the game.[36] However, Ranjitsinhji had neither the strength nor the range of batting strokes to succeed at this stage.[38]

Around this time, Ranjitsinhji began to work with Daniel Hayward, a first-class cricketer and the father of future England batsman Thomas Hayward, on his batting technique. His main fault was a tendency to back away from the ball when facing a fast bowler, making it more likely he would be dismissed. Possibly prompted by the suggestion of a professional cricketer who was bowling at him in the nets at Cambridge, he and Hayward began to practise with Ranjitsinhji's right leg tied to the ground. This affected his future batting technique and contributed to his creation of the leg glance, a shot with which he afterwards became associated.[39] While practising, he continued to move his left leg, which was not tied, away from the ball; in this case, it moved to his right, towards point. He found he could then flick the ball behind his legs, a highly unorthodox shot and likely, for most players, to result in their dismissal.[40] Although other players had probably played this shot before, Ranjitsinhji was able to play it with unprecedented effectiveness.[41] Ranjitsinhji probably developed his leg glance with Hayward around spring 1892, for during the remainder of that year, he scored around 2,000 runs in all cricket, far more than he had previously managed,[40] making at least nine centuries, a feat he had never previously achieved in England.[42]

Ranjitsinhji began to establish a reputation for unorthodox cricket, and attracted some interest to his play,[43] but important cricketers did not take him seriously as he played contrary to the accepted way for an amateur or university batsman, established by the conventions in English public schools.[44] In one match, he was observed by the captain of the Cambridge University cricket team and future England captain Stanley Jackson, who found his batting and probably his appearance unusual but was not impressed.[43][45]

University cricketer

At least one Cambridge University cricketer believed that Ranjitsinhji should have played for the team in 1892; he played in two trial games with moderate success, but Jackson believed he was not good enough to play first-class cricket. Jackson was probably also the reason Ranjitisinhji did not play cricket for Trinity College until 1892, despite his success for other teams.[46] Jackson himself wrote in 1933 that, at the time, he lacked a "sympathetic interest for Indians",[43] and Simon Wilde has suggested that prejudice lay behind Jackson's attitude.[46] Jackson also said in 1893 that underestimating Ranjitsinhji's ability was a big mistake.[47] However, Ranjitsinhji made his debut for Trinity in 1892 after injury ruled out another player and his subsequent form, including a century, kept him in the college team, achieving a batting average of 44, only Jackson averaging more.[31][48] However, the other players ignored Ranjitsinhji in these matches.[31] That June, watched by Ranjitsinhji, Cambridge were defeated by Oxford in the University Match; Malcolm Jardine, an Oxford batsman, hit 140 runs, many with a version of the leg glance; Jackson would not alter his tactics and Jardine was able to score easy runs.[31]

That winter, Jackson had taken part in a cricket tour of India, where he was impressed by the standard of cricket.[43][49] When he observed, at the start of the 1893 cricket season, the dedication with which Ranjitsinhji was practising in the nets to increase his concentration against the highly regarded professional bowlers Tom Richardson and Bill Lockwood,[50] Jackson asked Lockwood for his opinion. Lockwood noted how much Ranjitsinhji had improved through practice and told Jackson he believed Ranjitsinhji was better than several players in the University team.[51] Then, Ranjitsinhji's early form in 1893, scoring heavily for Trinity and performing reasonably well in a trial match, convinced Jackson. He made his first-class debut for Cambridge on 8 May 1893 against a team selected by Charles Thornton; he batted at number nine in the batting order and scored 18.[37][51] He maintained his place in the side over the next weeks, making substantial scores in several innings against bowlers with a good reputation. He grew in confidence as the season progressed; critics commented on several occasions on the effectiveness of his cut shot and his fielding was regarded as exceptionally good.[32][52] His highest and most notable score came during a defeat by the Australian touring team when he made 58 runs in 105 minutes, followed by a two-hour 37 not out in difficult batting conditions during the second innings. His batting made a great impression on spectators, who gave him an ovation at the end of the game. The game appears to be the first occasion in first-class cricket where Ranjitsinhji used the leg glance.[52][53] Ranjitsinhji was awarded his Blue after the match, and following some more successful but brief innings, he played in the University match. He was given a good reception by the crowd but scored only 9 and 0 in the game, which his team won.[37][54] With the Cambridge season over, Ranjitsinhji's batting average of 29.90 placed him third in the side's averages, with five scores over 40. He took nineteen catches, mainly at slip.[55][56] Such was his impact that Ranjitsinhji was selected in representative games, playing for the Gentlemen against the Players at the Oval and for a team combining past and present players for both Oxford and Cambridge Universities against the Australians, scoring a total of 50 runs in three innings.[55][56]

Following his success at cricket, Ranjitsinhji was more widely accepted within Trinity.[32][57] His new-found popularity led to the creation by his friends of a nickname; finding his name difficult, they initially dubbed him "Smith", then shortened his full name to "Ranji", which remained with him for the rest of his life.[58][59] At this time, Ranjitsinhji may have furthered rumours of his royal background or great wealth, and he was further encouraged to spend money to entertain others and reinforce the impression of his status.[32][57] Several English first-class counties made enquiries over his availability to play for them, and he was invited to make a speech at a Cambridge club dinner, attended by prominent figures in Cambridge; his general remarks about the good treatment of Indians in England were reported in the press as being in support of Indian federation and suggested the public were eager to hear his words.[60] However, Ranjitsinhji was unable to continue his cricket with Cambridge as he had to leave before the start of the 1894 season.[61]

First spell with Sussex

County debut

Following his failure to take the Bar examinations and return to India, Ranjitsinhji's allowance was stopped by Vibhaji. Ranjitsinhji, owing money to many creditors in Cambridge who included personal friends, appealed to the British in India and Vibhaji was persuaded to advance a loan to cover Ranjitsinhji's expenses before his expected return to India.[62] Simon Wilde believes this incident encouraged a belief in Ranjitsinhji that someone else would always cover his debts.[63] Even so, he was not called to the Bar in 1894, or at any point afterwards. Nor did he make any attempt to return to India, despite his assurances to Vibhaji. Instead, his developing friendship with Billy Murdoch and C. B. Fry led to Ranjitsinhji becoming interested in playing cricket for Sussex.[64] Murdoch, the Sussex captain, wished to increase his team's playing strength. It is likely that, although he would play as an amateur, the club offered Ranjitsinhji a financial inducement, as was common for leading amateurs; given his monetary difficulties and unwillingness to return home, he was unlikely to refuse the offer.[65] However, these arrangements came too late for Ranjitsinhji to play for the county in 1894, and his cricket that year was limited to matches for the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), festival games and benefit matches. Consequently, he could neither find any batting form nor build on his achievements of the previous year. Although struggling to bat against off spin in one game, he scored 94 while sharing a partnership of 200 runs with W. G. Grace in another.[66][67] In eight first-class games, he scored 387 runs at an average of 32.25.[68]

Despite debts which continued to mount,[69] Ranjitsinhji prepared thoroughly before the 1895 season, practising in the nets at Cambridge with Tom Hayward and scoring heavily in club matches.[70] Although Sussex were not a strong team, Ranjitsinhji was not certain of a place in the side.[71] His debut came in a match against the MCC; after scoring 77 not out in his first innings and then taking six wickets, he scored his maiden first-class century in the second. In 155 minutes, he scored 150 runs and took his team close to an improbable victory; he became increasingly attacking throughout the innings and dominated the scoring. At the end, although his team lost, he was given an ovation by the crowd who were impressed by his strokeplay.[72] Yet it is unlikely that he met the qualification rules in force at the time for appearing in the County Championship; this was hinted at by Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, but no protests were made.[70]

For the rest of the season, Ranjitsinhji made a vivid impression wherever he played. Crowds were substantially increased at matches in which he appeared and he established a reputation for brilliant batting and shots on the leg side.[73] Although, after his debut, he made a slow start in poor weather, he batted himself into good form in several matches on Brighton's good batting pitch. He scored centuries against Middlesex and Nottinghamshire in very difficult batting conditions, and his batting against the latter was regarded by critics as among the best of the season.[74] He was less effective at the end of the season, possibly suffering from mental and physical fatigue, but his overall record of 1,775 runs at an average of 49.31 placed him fourth in the national averages.[68][75] Ranjitsinhji was particularly popular at Brighton; Simon Wilde writes: "The crowds would stroll the outfield during intervals in play ... at a loss to explain what he did: the most disdainful flick of the wrists, and he could exasperate some of England's finest bowlers; the most rapid sweep of the arms, and the ball was charmed to any part of the field he chose, as though he had in his hands not a bat but a wizard's wand."[76]

Shortly before the season began, Vibhaji died; his 12-year-old son Jaswantsinhji officially succeeded to the throne on 10 May, while Ranjitsinhji was playing for Sussex against the MCC, taking the new name Jassaji. The British appointed an Administrator to rule until he reached an appropriate age to assume the responsibility of a ruler.[77] As Ranjitsinhji's fame increased throughout 1895, journalists pressed for more information on his background. Some stories circulated that his father was the ruler of an Indian state and that he had been deprived of his rightful position as ruler of Nawanagar; despite his protestations that this was not correct, it is likely that Ranjitsinhji was the source of these stories. It is possible he began planning to contest the position, prompted by the enquiries of the press and his claim to be a prince.[78]

Test debut and controversy

Ranjitsinhji played several large innings at the start of the 1896 season, scoring faster and impressing critics with more daring shots. Before June, he had hit hundreds against the highly regarded Yorkshire bowlers and in match-saving performances against Gloucestershire and Somerset and became the second batsman, and first amateur, to reach 1,000 runs in the season. Innings of 79 and 42 against the touring Australian team underlined his status as one of the few batsmen to cope with the visitors' bowling spearhead, the highly regarded Ernie Jones; he concentrated on the leg-glance and cut shot, which the Australians were unable to counter through altered tactics.[37][79]

These performances brought him into contention for a place in the England team for the first Test match, but although his form merited selection, he was not chosen by the MCC committee which chose the team. Lord Harris was primarily responsible for the decision, possibly under influence from the British Government; Simon Wilde believed they may have feared establishing a precedent that made races interchangeable or wished to curtail the involvement of Indians in British political life.[80] Bateman's assessment is less sympathetic to Harris: "the high-minded imperialist Lord Harris, who had just returned from a spell of colonial duty in India, opposed his qualification for England on the grounds of race."[81]

Even so, the decision to omit Ranjitsinhji took a long time, proved unpopular when it was made and led to discussion in the press.[82] The Times correspondent commented during the first Test: "There was some feeling about K. S. Ranjitsinhji's absence, but although the Indian Prince has learnt all his cricket in England he could scarcely, if the title of the match were to be adhered to, have been included in the English eleven",[83] but The Field supported his inclusion.[82] Meanwhile, Ranjitsinhji's good form continued. The team for the second Test was chosen by a different committee,[note 4] and Ranjitsinhji was included, probably for financial reasons to attract more spectators.[82] The batsman insisted that he would only play if the Australian team had no objections, but the Australian captain was pleased that the Indian would be included.[84] Discussion continued in the press over how appropriate it was that he should play for England, but from that point, Ranjitsinhji was considered eligible to play for England. The controversy may have upset Ranjitsinhji as his form wavered while the first Test was played and on his next appearance at Lord's, before the MCC committee, he made a pointed attack on the bowling in a rapid innings of 47.[85]

Ranjitsinhji made his Test debut on 16 July 1896. After a cautious 62 in his first innings, he batted again when England followed on, 181 runs behind. After the second day, he had scored 42 and on the final morning, he scored 113 runs before the lunch interval, surviving a fast, hostile spell from Jones and playing many shots on the leg side to reach the first century scored that season against the tourists. His final score was 154 not out,[86] and the next highest score for England on the last day was 19. He was given an enthusiastic reception by the crowd and the report in Wisden stated: "[The] famous young Indian fairly rose to the occasion, playing an innings that could, without exaggeration, be fairly described as marvellous. He ... punished the Australian bowlers in a style that, up to that period of the season, no other English batsman had approached. He repeatedly brought off his wonderful strokes on the leg side, and for a while had the Australian bowlers quite at his mercy."[87] Although Australia won the match, the players were astonished by the way Ranjitsinhji batted.[88] Not everyone was pleased at his success. Home Gordon, a journalist, praised Ranjitsinhji in a conversation with an MCC member; the man angrily threatened to have Gordon expelled from the MCC for "having the disgusting degeneracy to praise a dirty black." Gordon also heard other MCC members complaining about "a nigger showing us how to play the game of cricket".[89]

Over the next weeks, Ranjitsinhji lost form, and after failing twice in the third Test, missed the last day of the match suffering from asthma,[90] but he scored heavily after this. After sharing a big partnership with Fry for Sussex against the Australian team, he scored 40 and 165, with little support from other batsmen, to save the match against Lancashire, the runners up in the County Championship. In the following match against Yorkshire, on 22 August 1896, the County Champions that season, he scored two centuries on the last day of the game as Sussex saved the match after following on; prior to this, only four men had scored two centuries in the same first-class game, and as of 2011, no one else has scored two on the same day.[91][92] By the end of the season, he had scored 2,780 runs, beating the record aggregate for a season held by W. G. Grace, and hit 10 centuries, equalling another record of Grace. His average of 57.92 was the highest of the season.[68][93] Even so, Sussex finished bottom of the County Championship as Ranjitsinhji had little batting support and the team's bowling was ineffective.[94]

Succession dispute

Ranjitsinhji's fame increased after 1896, and among the praise for his cricket were hints in the press that he intended to pursue a political career, following other Indians in England. Instead he began to turn his attention to the Nawanagar succession, beginning to make enquiries in India as to his position.[95] Meanwhile, he began to cultivate potentially beneficial connections; at Queen Victoria's jubilee celebrations, he established a friendship with Pratap Singh, the regent of Jodhpur, whom he later falsely described as his uncle.[96] Ranjitsinhji decided to return to India to further his case, prompted by the decision of Vibhaji's grandson Lakhuba to dispute the succession. Meanwhile, the financial expectations of behaving as a prince pushed Ranjitsinhji even further into debt, and his allowance had been stopped after he had been given an advance on it to cover earlier money owed. He wrote to Willoughby Kennedy, the English Administrator of Nawanagar, asking for money but none was forthcoming.[96][97] His financial situation eased when a serious illness confined him to the house of an acquaintance. He took the opportunity to begin work on a cricket book which a publisher had invited him to write; Ranjitsinhji contributed seven chapters and other writers contributed the rest, then he and Fry revised the book together while travelling through Europe in the spring of 1897. The book was released in August 1897 under the title The Jubilee Book of Cricket,[note 5] and was a success, both commercially and with the critics:[98] the review by Francis Thompson was entitled, "A Prince of India on the Prince of Games".[81] Nevertheless, he was approaching bankruptcy by the end of 1897 and there are indications, such as an increased temper, that he felt the pressure.[96]

Having been named one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year for his performances in 1896,[47] Ranjitsinhji began the 1897 season strongly, scoring 260 for Sussex against the MCC then, playing for MCC against Lancashire hit 157. A succession of low scores on a series of difficult pitches ended when he scored three centuries in July, but in the remainder of the season he only once passed fifty.[37][99] He scored 1,940 runs at 45.12, figures which matched other leading batsmen, but his relative loss of form, noted by critics, was owed partly to ill health. He suffered from asthma throughout the season, and some commentators blamed the stress of producing his book. However, he may also have been distracted by his interest in the Nawanagar succession.[100]

Tour of Australia

Ranjitsinhji was chosen to tour Australia with Andrew Stoddart's team during the winter of 1897–98. The team was defeated 4–1 by Australia, who were superior tactically and had the better players in general.[100][101] Ranjitsinhji was one of the few successes on the tour and scored 1,157 runs in first-class matches at an average of 60.89.[68][100] He quickly acclimatised to the unfamiliar conditions and scored 189 in the first game, followed by scores of 64 and 112 in the following two matches.[37][102] However, shortly before the Test series was due to begin, Ranjitsinhji fell ill with quinsy and would have been unfit for the first Test but for heavy rain which postponed the start for three days.[103] When the match began, Ranjitsinhji batted towards the end of the first day and, still weak from his illness, played carefully; he was exhausted after scoring 39 not out. The next morning, as England lost wickets, he attacked the bowlers and took his score to 175, scoring mainly from cuts and leg glances. He batted for 215 minutes and reached the highest score for England in Test matches; the record lasted for six years. England won the match by nine wickets, but this was their only success of the series.[104]

Ranjitsinhji's health remained poor, but he played in the rest of the series.[105] He scored a half-century in one innings of each of the next three Tests, each time facing a large Australian total. He and Archie MacLaren were the only two tourists to come to terms with the conditions and bowling; despite being labelled a poor starter by the press, Ranjitsinhji batted cautiously in each match, possibly attempting to emulate the Australian approach of accumulating runs carefully.[37][106] The only Test in which Ranjitsinhji failed to reach fifty was the fifth, when England were defeated for the fourth time in succession.[37] Even so, he scored 457 runs at an average of 50.77 in the series.[107]

Ranjitsinhji's tour was controversial in one aspect only: a series of articles he wrote for an Australian magazine. Although highly self-critical in the articles, he criticised, among other things, the behaviour of the crowds, the refusal of Australian critics to accept that England had to bat in poor conditions in the second Test, and some opposing players. He also supported the decision of an umpire to no-ball some deliveries from Ernie Jones, in a match against Stoddart's team, for illegally throwing the ball rather than bowling it. He was generally very popular in Australia with crowds, the general public and influential figures in society,[108] although following these comments, the crowds at some matches barracked him while he was batting.[109] At the end of the tour, he wrote an open letter to mend his relations with the Australian public,[109] but in With Stodard's team in Australia, he wrote of the "regrettable" incident of "merciless", "uncomplimentary and insulting" barracking.[110]

Cricketing peak and decline

Return to India

In April 1898, Stoddart's cricket team returned to England via Colombo. On arrival there, Ranjitsinhji left the team to return to India with the intention of pursuing his claim to the throne of Nawanagar.[100][111] He spent the remainder of the year in India and did not return to England until March 1899.[112] Initially, he tried to establish support for his claim, including his argument that Jassaji was illegitimate, among the Indian princes. Later, he met Pratap Singh, who had arranged for Ranjitsinhji to receive an honorary state appointment with an associated income. Pratap Singh also introduced him to Rajinder Singh, the Maharaja of Patiala, a very wealthy individual. Rajinder was very pro-British and an enthusiastic cricketer and soon became friends with Ranjitsinhji; he subsequently provided Ranjitsinhji with another source of income.[113] Ranjitsinhji travelled extensively throughout India, trying to build support among the princes and local officials, and received an enthusiastic reception from the public wherever he went. He also spent time with his mother and family in Sarador.[114][115] He played plenty of cricket during his visit, with mixed success. Although he scored 257 in one game, in another he failed to score in either innings, the only time this happened to him in any form of cricket.[116]

The British administration in India were concerned by Ranjitsinhji; some individuals suspected that he intended to cause trouble in Nawanagar and wished to keep him out of the region. Others supported him, believing he had been treated unfairly. Kennedy, the Administrator of Nawanagar, successfully lobbied the Government of Bombay and the India Office in London to have Ranjitsinhji's allowance doubled. But concerns among senior figures in the Government of Bombay about whether this was appropriate and over any potential agitation in Nawanagar by Ranjitsinhji meant that Kennedy's appeal to have the allowance further increased was unsuccessful.[117] However, the increase was dependent upon him no longer pursuing his claim to the throne and not becoming involved in any plots in Nawanagar, and Ranjitsinhji was reluctant to have any conditions imposed on him.[118] Then on 28 September, Ranjitsinhji wrote to the Secretary of State for India, Lord George Hamilton, through the Government of Bombay, stating his claim. He argued that he had been adopted as heir before being set aside without an enquiry, and that Jassaji was illegitimate.[119] The Government of Bombay rejected the appeal but Ranjitsinhji was able to use his contact with Rajinder Singh to meet the Viceroy, Lord Elgin. Consequently, the Government of India began to investigate and under Elgin's successor, Lord Curzon, Ranjitsinhji's application was sent to Hamilton in London.[120] Eventually, after Ranjitsinhji had returned to England, Hamilton also rejected the claim, but Simon Wilde believes the support he received from the princes and British officials, and the failure of anyone to point out that his adoption by Vibhaji was never carried out, must have encouraged Ranjitsinhji that his claim was viable.[121] Having done all he could in India for the moment, he returned to England in March 1899.[112]

Record breaker

Returning to England at the beginning of the 1899 cricket season, Ranjitsinhji immediately resumed playing cricket.[122] However, his approach to batting had changed during his absence, and he showed greater determination to succeed. His health seemed improved and financial assistance from his supporters in India gave him respite from monetary worries.[123] Having increased in weight, he was more noticeably muscular and could drive more effectively than previously.[122][124] After an uncertain start on a series of difficult pitches for batting, he informed the selectors he would not play in the first Test against the Australians, who were touring England once again.[125] He was selected anyway and after scoring 42 in the first innings, he hit 93 not out in the second which ensured England drew the match after losing early wickets on the last day. His tactics were unorthodox as he took risks to ensure that he faced most of the bowling, even though he was batting with recognised batsmen. However, as the innings progressed, he rediscovered his batting touch.[126] During June, he scored 1,000 runs: he scored four centuries, including a score of 197 which saved the game against Surrey, the eventual County Champions.[127] He scored runs against the strong bowling of Lancashire and Yorkshire, and in August embarked on a sequence of 12 innings in which his lowest scores were 42 and 48 which enabled him to score 1,000 runs in August; no-one had previously scored 1,000 runs in two separate months of the same season. In total, he scored 3,159 runs at an average of 63.18, becoming the first batsman to pass 3,000 first-class runs in a season, and made eight centuries.[68][128] He was less successful against the Australians after the first Test, possibly through over-anxiety to replicate his form for Sussex. He was dismissed for low scores in the second and third games, but was slightly more successful with 21 and 49 not out in the fourth and he hit 54 in the final match. In a low-scoring series, Ranjitsinhji scored 278 runs at 46.33, the second highest average for England.[107][129]

In June 1899, Ranjitsinhji was appointed Sussex captain after Murdoch retired, ahead of other amateur cricketers. George Brann captained the county's first match after Murdoch stood down but he may have found the position to be too difficult and Ranjitsinhji led the team for the remainder of the season.[130] The press regarded his first season as a success as a late sequence of matches without defeat took Sussex to fifth in the County Championship, the highest position achieved by the team to that point.[131] As captain, Ranjitsinhji took great care over details such as weather conditions, but some of his innovations, such as the frequent changing of the person bowling or implementing fielding practice, were unpopular with the players. He took the opportunity of leading the side to increase the amount of bowling he did, taking 31 wickets in the season.[132] But the team's lack of effective bowlers was a problem before Ranjitsinhji took over.[133]

Ranjitsinhji continued to score heavily throughout the 1900 season. After a slow start in cold weather, in the space of nine days, he hit scores of 97, 127, 222 and 215 not out, followed by 192 a week later.[134] After a brief sequence of low scores, he scored 1,000 runs in July and maintained his form until the end of the season; in his final 19 innings, he failed to reach 40 only three times. He was successful in a variety of conditions and match situations, and after some criticism of his ability to play on difficult pitches for batting, scored 89 against Somerset and 202 against Middlesex on rain affected pitches. Against Leicestershire, he achieved his highest score until then, making 275 in five hours.[135] He hit a record-breaking fifth double-hundred of the season in his penultimate game; this was his eleventh century of the season, which was also briefly a record.[note 6][137] Ranjitsinhji's final aggregate was 3,065 runs, the second highest total after that which he scored the previous year, at an average of 87.57; this placed him at the top of the national averages.[138][139]

In response to Ranjitsinhji's success, opposing captains began to adopt tactics to counter his leg-side shots, placing extra fielders on that side of the pitch to either block runs or to catch the ball. Consequently, Ranjitsinhji played the drive more frequently. Wisden reported: "[He] became more and more a driving player ... Without abandoning his delightful leg-side strokes or beautifully timed cuts, he probably got the majority of his runs by drives—a notable change from his early years as a great cricketer."[138] His change of technique was effective statistically; he scored 2,468 runs at 70.51 and was third in the national averages.[68][139] However, he was less consistent than in the previous two seasons, never hitting more than three successive scores above 40. He suffered from ill-health early in the season and struggled in the first months. His later form was better and he made the highest score of his career, 285 against Somerset, but several leg break bowlers took his wicket and some of his innings were played in easier batting conditions or during less competitive circumstances.[140]

Failure in 1902

According to Simon Wilde, part of the reason for Ranjitsinhji's reduced output in 1901 was the death in November 1900 of Rajinder Singh; the subsequent reduction in his income would have presented Ranjitsinhji with financial difficulties.[141] By November 1901, Ranjitsinhji faced bankruptcy and after an unavailing request to Nawangar for a resumption and increase of his allowance, only an appeal to the India Office prevented a court action against him. Through his solicitor, Ranjitsinhji claimed that his debt to one creditor only came through his acting on behalf of Pratap Singh and Sardar Singh, the Maharaja of Jodhpur.[142] In December, Ranjitsinhji travelled to India to attempt to secure financial guarantees from the council acting for Rajinder Singh's son and from Jodhpur but he was unsuccessful in his attempt to get the support of the Maharao of Kutch, who was sympathetic but unwilling to help; he nevertheless later received a request for a substantial sum of money which Ranjitsinhji claimed he had been promised.[143] Ranjitsinhji's Indian trip caused him to miss the start of the 1902 season; no reason was given for his absence and the press and public did not know where he was.[note 7][144]

Ranjitsinhji returned to England in mid-May and immediately resumed the captaincy of Sussex. However, a succession of low scores and uncertain performances suggested that he was neither mentally nor physically fit for cricket and Simon Wilde writes that his failure to secure support in India and the continued pressure of threatened bankruptcy placed him in a difficult situation.[145] The Australian cricket team was touring England once more and Ranjitsinhji, having played against the team for the MCC, was selected for the first Test. However, he seemed to be nervous and struggled to concentrate, running out his captain, Archie MacLaren before he was out himself for 13.[37][146] Wisden noted: "a misunderstanding, for which Ranjitsinhji considered himself somewhat unjustly blamed, led to MacLaren being run out, and then Ranjitsinhji himself quite upset by what had happened, was clean bowled".[147] Although he scored 135 for Sussex shortly afterwards, in the second Test he was out without scoring.[37] Over the next few weeks, Ranjitsinhji made good starts to several innings but lost his wicket to uncharacteristic lapses and leg-break bowlers continued to trouble him.[37][148] He missed several matches, far more than he had missed in other seasons.[148][149] However, in favourable batting circumstances he played two large innings in this period, hitting 230 against Essex and 234 against Surrey.[37][148] An injury in the former game caused Ranjitsinhji to miss the third Test, lost by England, although his lack of confidence may have played a part in his decision.[150] He returned for the fourth Test which England narrowly lost. However, he faced serious distractions from his parlous financial situation as one of his creditors presented him with a demand for payment shortly before the game. Ranjitsinhji claimed after the match, falsely, that Pratap Singh intended to pay the debt but needed approval from the India Office, but it is likely that Ranjitsinhji anticipated another petition in bankruptcy going before a court and that this affected his performance in the Test.[151] Showing signs of nerves, and never looking comfortable while batting, Ranjitsinhji scored 2 runs in the first innings and 4 in the second. In the latter innings, when England had a relatively small target to chase for victory, he looked to have lost all confidence and could have been dismissed several times; the Australian players thought he played more poorly than they had ever seen. His lack of belief may also have contributed to the defeat, as Fred Tate notoriously dropped an important catch fielding, according to Simon Wilde, in a position which Ranjitsinhji was more likely to fill in normal circumstances.[151] Wilde writes: "[Several members of the team] failed to play their part, notably Ranji, whose abject performance was in marked contrast to his former days of splendour. The real reason for his poor performance has remained the knowledge of only a very few. At the time, a polite veil was drawn over his failure, but he was never to play for England again."[152] In 15 Test matches, all against Australia, he scored 989 runs at an average of 44.96.[139]

After the Test, Ranjitsinhji played only a few more games that season. After two batting failures for Sussex, he dropped out of the team, even though the side were in contention for the County Championship, eventually finishing second. Part of the reason may have been to pre-empt his omission from the England team for the final Test, a match he attended as a spectator, but he did not return to Sussex after the match. The press speculated he had walked out on the team; among the reasons suggested were disappointment with the performances of the side, dissatisfaction with the bowlers and efforts to recruit new players, and his falling out with the professional players. The local press criticised him for abandoning the team at a crucial phase of the season, and praised Brann, his replacement. Nevertheless, Ranjitsinhji preferred to play for MCC against the Australians, scoring 60 and 10.[153] His three substantial innings gave him a batting record for the season which partially masked his difficulties: 1, 106 runs at an average of 46.08, placing him second in the national averages.[68][139]

Ranjitsinhji managed to raise enough money, probably through a loan, to head off the threat of bankruptcy.[154] After spending time with Pratap Singh who was in London for the coronation of Edward VII, Ranjitsinhji went to Gilling East in Yorkshire, where the Reverend Borrisow now lived. He spent the winter there, adding to the speculation surrounding him. He became very close to Borrisow's eldest daughter, Edith, and the pair may have become engaged around this time.[155]

Final regular seasons

After alleviating some of his financial concerns through journalism and writing, Ranjitsinhji was able to return to cricket.[156] Like the previous season, cricket in 1903 was badly affected by weather, resulting in many difficult batting pitches. Ranjitsinhji scored 1,924 runs at 56.58 to achieve second place in the national batting averages, but his consistency never matched that of his earlier years and he was frustrated by his form. He played more regularly for Sussex and missed just two matches but displayed a reduced commitment to the club and resigned the captaincy in December, Fry assuming the role.[139][157] After a slow start, Ranjitsinhji found his form and made large scores against the leading counties until a pulled muscle affected his form in July. The difficult pitches forced him to play more defensively than usual and on a couple of occasions, crowds jeered him for slow scoring. The press also criticised his decision to prolong one Sussex innings until he had completed his own double century, adversely affecting his team's chances of victory. In separate matches, Len Braund and Walter Mead, bowlers who had troubled him in previous years, both took his wicket before he had scored many runs.[158] Ranjitsinhji was not considered for the MCC tour of Australia that winter, despite the unavailability of several leading amateurs; instead, he returned to India.[156] There, he made further inquiries regarding the succession to the Nawanagar throne and met British officials. Loans from an acquaintance from his school days, Mansur Khachar, as well as from the Nawab of Junagadh, allowed him to return to England for the following season.[159]

In 1904, Ranjitsinhji led the batting averages for the fourth time, scoring 2,077 runs at 74.17.[139] In a ten-week sequence between June and August, he scored eight hundreds and five fifties, including innings against strong attacks and the leading counties. This included a highest score of 207 not out against Lancashire where Wisden reported that "From the first ball to the last in that superb display he was at the highest pitch of excellence, and beyond that the art of batting cannot go." However, he missed eight Sussex games in total, suggesting his commitments had begun to lie elsewhere. Furthermore, many of his runs came in less important matches, away from the pressure of the County Championship.[160] Not initially invited to play for the Gentlemen at Lord's, he was a last minute replacement and subsequently captained the team. His innings of 121, regarded by some critics as one of his best innings, helped the team to score an unlikely 412 runs in the final innings to defeat the Players.[160] When the season ended with a series of festival games, although it was not known at the time, Ranjitsinhji's career as a regular cricketer was effectively over.[161]

Remainder of cricket career

Four years after his previous appearances, and now known as H. H. the Jam Sahib of Nawanagar, Ranjitsinhji returned to play cricket in England in 1908. Playing mainly in Sussex and London, he had put on weight and could no longer play in the same extravagant style he had previously used. Playing in many less competitive fixtures, he scored 1,138 runs at 45.52, finishing seventh in the averages.[139][162] The effect on Sussex was not positive; Wisden noted that the irregular appearances of Ranjitsinhji and Fry, the team captain, distracted the rest of the team.[163] In one match, Ranjitsinhji was responsible for the Sussex team failing to appear during a match, risking the forfeiture of the game, when he encouraged the team to remain at his residence in unsettled weather; conditions at the ground, and the opposition, were ready for play while the Sussex team remained 22 miles away.[164]

In 1912, aged 39, Ranjitsinhji returned to England and played once more. Although announcing himself available to play for England in that season's Test matches, he was not selected. Restricted for a period by a wrist injury, he nevertheless scored four centuries, including one against the touring Australian team. At times, his form briefly touched that of his best years but most of his cricket was played in the South of England. He scored 1,113 runs at 42.81, placing him eighth in the averages.[165] Ranjitsinhji's last first-class cricket came in 1920; having lost an eye in a hunting accident, he played only three matches and found he could not focus on the ball properly. Possibly prompted by embarrassment at his performance, he later claimed his sole motivation for returning was to write a book about batting with one eye; such a book was never published.[166]

In total, Ranjitsinhji scored 24,692 runs at an average of 56.37, the highest career average of a batsman based mainly in England until Geoffrey Boycott retired in 1986. He scored 72 hundreds.[139]

Jam Sahib of Nawanagar

Return to India

Despite the discovery of an assassination plot on his life, in which Ranjitsinhji was implicated,[167] Jassaji took over the administration of Nawanagar from the British in March 1903. Roland Wild later described it as "the shattering of [Ranjitsinhji's] dreams".[161] During the 1904 season, Ranjitsinhji had a long meeting with Lord Curzon during a Sussex match. Immediately afterwards, he chose to miss three Championship games at short notice and visited Edith Borrisow in Gilling for 10 days; Simon Wilde suggests that Ranjitsinhji had at this point chosen to leave for India after the cricket season.[168]

On 9 October 1904, Ranjitsinhji departed for India, accompanied by Archie MacLaren, with whom Ranjitsinhji had developed a close friendship on the tour to Australia in 1897–98, and who now became his personal secretary.[100][168] In India, Ranjitsinhji and MacLaren were joined by Mansur Khachar and Lord Hawke, the Yorkshire captain. Ranjitsinhji tried unsuccessfully to arrange an official meeting with Curzon to discuss the succession to Nawanagar and then chose to remain in India to cultivate his relationships with British officials, although there was little chance he could achieve much with regard to Nawanagar.[169] MacLaren returned to England ready for the 1905 season and Ranjitsinhji may have intended to follow. Instead, Mansur Khuchar discovered that Ranjitsinhji had attempted to trick him into providing more money and had repeatedly lied to him; in May 1905 he took Ranjitsinhji to Bombay High Court, insisting Ranjitsinhji repaid the money lent to him. This action kept him in India throughout 1905 and most of 1906 and prevented his return to England, where his absence was noted but could not be explained.[170]

Succession

Although he had been in good health, Jassaji died on 14 August 1906 after developing a fever two weeks previously. Although no surviving papers suggest foul play, according to Simon Wilde there is circumstantial evidence that Jassaji may have been poisoned; at least one later ruler of Nawanagar believed that Ranjitsinhji had plotted Jassaji's murder.[171] Contrary to precedent, British officials did not make a decision over his successor for six months. The three major claimants who presented a case were Ranjitsinhji, Lakhuba and Jassaji's widows. Ranjitsinhji's claim once again rested on his claim to have been adopted by Vibhaji; Lakhuba claimed the throne through his position as Vibhaji's grandson, and like Ranjitsinhji, his prior claims had been rejected. Jassaji's widows claimed through precedent that they should choose a successor as Jassaji had not done so.[172]

Taking advantage of being in India, Ranjitsinhji quickly persuaded Mansur Khachar to withdraw his court claim in return for paying him in full upon his succession. He also secured declarations of direct or partial support from several other states. He also used British newspapers to further his claim.[173] After examining the case, the British found in favour of Ranjitsinhji in December 1906, although the decision was not made public until the following February. Simon Wilde points out that the decision explicitly contradicted the evidence provided by the widows and seemingly ignored Vibhaji's abandonment of Ranjitsinhji as heir. Nevertheless, Ranjitsinhji's popularity as a cricketer, his close connections with many of the British administrators and the fact that he was westernised from his time spent in England may all have been major factors in the decision according to Wilde.[174]

An appeal from Lakhuba, which was eventually unsuccessful, delayed proceedings but Ranjitsinhji was installed as Jam Sahib on 11 March 1907.[175] The installation was relatively simple for financial reasons as Nawanagar was poor; many items had to be borrowed from neighbouring states for the ceremony to reach the expected standard. Security was heavy and shortly after the ceremony and in unfamiliar surroundings, Ranjitsinhji secretly adopted a nephew as his heir.[176]

Ranjitsinhji faced many challenges upon assuming control of Nawanagar. The state, following a drought several years before, was poor, suffered poverty and disease. In 1907, approximately thirty people were dying from disease each day in the capital city, Jamnagar. When he first saw it, Ranjitsinhji described Jamnagar as "an evil slum". To provide funds, most of the state's jewellery had been sold off.[177] In a speech at Ranjitsinhji's installation, Percy Fitzgerald, the British resident at Rajkot, made clear that the state needed to be modernised; for example, he said that Ranjtisinhji should develop the harbour at Salaya and extend the state's railway, improve irrigation and reform the state's administration.[178] The British also took steps to reduce spending, concerned about his personal financial difficulties.[179] According to Simon Wilde, Ranjitsinhji must have suffered from personal insecurity, moving to a region with which he was unfamiliar; furthermore, it is unlikely that his expectations before he became ruler were matched by the reality.[180]

Possibly prompted by his difficulty adjusting, Ranjitsinhji made little progress in his first four months. He made enquiries into improving the collection of his land revenue, began to build a cricket pitch and went on shooting expeditions.[181] Then in August 1907, he became seriously ill with typhoid, although he later claimed he had been poisoned. He recovered well, but his doctor reported to Fitzgerald that Ranjitsinhji needed a year in England to recover. Fitzgerald had misgivings about the level of expenditure involved and was concerned that opponents might plot while the ruler was away, but had to accept the decision.[182]

Controversy in England

Upon arriving in England, Ranjitsinhji hired a country house at Shillinglee and spent much of his time entertaining guests, hunting and playing cricket. Such a lifestyle was expensive, but there is no evidence he paid many bills and ran up considerable debts.[183] Freed from his previous financial difficulties, he seems to have tried to repay the hospitality he had enjoyed. However, he made no attempt to pay for his lifestyle and ignored any requests for payment sent to him.[184] Nevertheless, he came under increasing financial pressure throughout 1908. Mansur Khachar came to England in an attempt to recover his loan, and contacted the India Office. He claimed Ranjitsinhji repeatedly misled him, although he could not provide evidence for all of his statements. Ranjitsinhji denied many of the claims but agreed to repay the initial loan to prevent embarrassment if the story got out. He offered to repay half of the sum, but in the event gave back less than a quarter.[185] Another dispute arose with Mary Tayler, an artist who was commissioned in April 1908 to create a miniature portrait of Ranjitsinhji at an agreed cost of 100 guineas for one and 180 guineas for a pair. Ranjitsinhji became increasingly uncooperative and when the finished work arrived two weeks afterwards, he eventually returned them, stating that he was dissatisfied with the likeness. In response, Tayler issued a writ for 180 guineas.[186] When the case came up at Brighton county court, Ranjitsinhji's solicitor, Edward Hunt, claimed that as a ruling sovereign, English courts had no authority over him.[187] However the Secretary of State for India, Lord Morley, became involved and Hunt offered to make a settlement. By August, after a delay of seven weeks, Tayler was told that the matter could not be settled as MacLaren, Ranjitsinhji's secretary and a vital witness, was injured. But when Tayler discovered that this was untrue,[note 8] she wrote to the India Office. She had no proof that a fee was agreed, but in November the India Office decided Ranjitsinhji should pay £75 as a gesture of good faith, and criticised Ranjitsinhji and "his ridiculous private secretary".[189] Ranjitsinhji also came before the courts over an 1896 loan covenant in a dispute between four women and himself and three other people. Ranjitsinhji had his name taken out of the claim on the grounds that he was a ruling sovereign, a view which was supported by the India Office.[190]

During his visit Ranjitsinhji resumed his first-class cricket career in the 1908 season,[191] and also visited the Borrisow family in Gilling East. At the time, he was contemplating marriage and locals believed he was in love with Edith Borrisow. While he may have pursued the matter, objections from her father and the potential scandal in both British and Rajput circles at a mixed-race marriage prevented anything coming of it.[192] In August 1908, Ranjitsinhji became involved in fund raising to restore the bell-tower of Gilling East parish church and to furnish it with a clock; he organised a cricket match involving famous cricketers playing against a local team and raised money through the sale of a photograph.[193]

By the end of the season, Ranjitsinhji was under pressure. At a farewell dinner to celebrate his cricket feats, some notable figures from cricket and the India Office were absent.. Rumours spread over his financial unreliability and stories appeared in the press that he was considering abdication.[194] He felt betrayed by the government and criticised it in a speech at the dinner, and he felt unfairly blamed for the financial controversy.[195] However, Horatio Bottomley, a Liberal MP began to publicly criticise Ranjitsinhji in his magazine John Bull in October and November, drawing attention to his debts, the court cases and the claim that he was exempt from the law. Concerned and embarrassed by the negative publicity, the India Office advised Ranjitsinhji to be more careful with money.[196] Ranjitsinhji wrote back that he was "very hurt and annoyed at being continually thought ill of",[197] and also defended himself in a letter to the Times. In December 1908, he returned to India although two months remained on his lease at Shillinglee.[198]

First years as ruler

Ranjitsinhji returned from England to find that many of his staff had left and several assassination plans had been uncovered. Rumours spread that he was about to abdicate.[199] Despite the help of British officials, he made several controversial decisions, accumulated expensive possessions and attempted to increase his income. He tried to reclaim land given away by previous rulers and although he reduced revenue taxation, he imposed an additional land rent which, coupled with severe drought, led to rebellion in some villages; Ranjitsinhji ordered his army to destroy them in retribution.[200] The new resident at Rajkot, Claude Hill, was concerned by Ranjitsinhji's actions early in 1909 and met him April 1909 to discuss his role and responsibilities.[201] Meanwhile, in England Lord Edward Winterton, to whom Ranjitsinhji owed money from his lease of the Shillinglee Park property, asked questions in the House of Commons regarding Ranjitsinhji's debts, visits to England and his actions as ruler of Nawanagar.[202] As his state required his presence, the British advised him to leave at least four years between his visits to England. He did so at the earliest opportunity in 1912.[203]

Ranjitsinhji resumed first-class cricket in 1912 but also had to face his many debts in England; his solicitor, Hunt, was questioned by the India Office, although Hunt reassured the officials that Ranjitsinhji's debts were in hand. Lord Winterton once again asked questions in the House of Commons, this time about money Ranjitsinhji owed to the Coupe Company for architectural designs. Ranjitsinhji appeared himself at the India Office to answer questions on this particular debt and eventually paid back £500 of the £900 he owed.[204] After spending time with Edith in Gilling, Ranjitsinhji returned to India in January 1913, pursued once more by rumours of impending marriage.[205] Although Ranjitsinhji continued to state his intention to marry, and plans for a wedding were fairly developed, he never married. However, it is possible that Edith Borrisow stayed regularly at the palace.[note 9] [206]

War service and loss of eye

When the First World War began in August 1914, Ranjitsinhji declared that the resources of his state were available to Britain, including a house that he owned at Staines which was converted into a hospital. In November 1914, he left to serve at the Western Front, leaving Berthon as administrator.[note 10][207] Ranjitsinhji was made an honorary major in the British Army, but as any serving Indian princes were not allowed near the fighting by the British because of the risk involved, he did not see active service. Ranjitsinhji went to France but the cold weather badly affected his health and he returned to England several times.[208] On 31 August 1915, he took part in a grouse shooting party on the Yorkshire Moors near Langdale End. While on foot, he was accidentally shot in the right eye by another member of the party. After travelling to Leeds via the railway at Scarborough, a specialist removed the badly damaged eye on 2 August. Ranjitsinhji's presence on a grouse shoot was a source of embarrassment to the authorities, who attempted to justify his presence in the area by hinting at his involvement in military business. He spent two months recuperating in Scarborough and after attending the funeral of W. G. Grace in Kent, he went to India for his sister's marriage and did not return to England before the end of the war.[209]

When Ranjitsinhji returned to India in 1915, Edith Borrisow remained in England. Her father died in 1917 and she and her sister moved away from Gilling, eventually settling in Staines (where Ranjitsinhji had a house).[210] According to cricket writer E. H. D. Sewell, to whom Ranjitsinhji told the story, Ranjitsinhji asked Edith to marry him following her father's death. However, she refused as she had fallen in love with someone else, and the engagement ended after 18 years. Sewell also claimed that her father had come to approve of the proposed marriage. However, the story may not be reliable and Simon Wilde speculates that Borrisow had simply tired of waiting and broke off the engagement. It is likely the pair remained friends, but Ranjitsinhji was deeply affected by the end of the relationship.[211]

Final years

Improvements in Nawanagar

While Ranjitsinhji was in Europe at the start of the war, Berthon remained in Nawanagar as Administrator and began to implement modernisation programmes. He organised the clearance of slums in Jamnagar and new houses, shops and roads were built. Berthon's improvements in irrigation meant that dry weather in 1923 was inconvenient but not disastrous like previous droughts. He also improved the state's finances to the extent that the railway was finally extended as the British resident had suggested in 1907.[212] Berthon continued in his role as Ranjitsinhji recovered from his injury, and the British Government wished him to remain in the position even when Ranjitsinhji was fully fit. Ranjitsinhji disagreed and threatened to abdicate if he was forced to retain Berthon. As a compromise, Berthon remained in Nawanagar but in an ostensibly more lowly position; in return, Ranjitsinhji was given more outward displays of favour, including the upgrading of Nawanagar to a 13-gun salute state and the centre of its liaison with the British was transferred from the Government of Bombay to the Government of India. Furthermore, Ranjitsinhji personally was entitled to a 15-gun salute[note 11] and officially granted the title of Maharaja.[212] Berthon retired in 1920 but remained close to Ranjitsinhji for many years.[216]

Nawanagar's finances were improved further by the construction of a port at Bedi. Encouraged by the British, the port was successful and thanks to favourable costs and charges it was used by many traders. As a consequence, Nawanagar's revenue more than doubled between 1916 and 1925.[216] Ranjitsinhji was therefore able to live in luxury. He acquired many properties in India, and while retaining his property in Staines in England, bought a castle in Ballynahinch on the west coast of Ireland. From 1920, he once more visited England but could now do so regularly and subsequently split his time each year between India and the British Isles.[217]

However, according to journalist Simon Wilde, Ranjitsinhji was never happy. Possibly, he felt more at home in England and in the company of his British friends, and never felt a connection with Nawanagar.[218] He was criticised for his failure to support Indian cricket, and his nephew Duleepsinhji later represented England in Test matches.[219] Furthermore, his relations with British officials in India deteriorated over his final years, descending into disputes over minor matters, such as the refusal of the Bombay Gymkhana to give him membership.[220]

Although Ranjitsinhji had no children, he was very close to his nephews and nieces; they lived in his palaces and he sent them to Britain to study. He encouraged his nephews to take up cricket and several of them had minor success in school cricket. The most effective was Duleepsinhji; critics spotted a similarity to Ranjitsinhji in his style and he had a successful county and Test career until he was forced to give up the game through illness in 1932. However, he felt pressured by Ranjitsinhji and said that he only played to keep Ranjitsinhji happy.[221]

Opposition to Federation and death

For much of the remainder of his life, Ranjitsinhji devoted his time to supporting the interests of the Indian Princes. He attempted to unite his fellow princes against the advance of democracy, the Independence Movement and the growing hostility of the Indian National Congress. He was instrumental in the formation of the Chamber of Princes.[222] Ranjitsinhji also secured a place on the Indian delegation to the League of Nations between 1920 and 1923, although he was a late replacement in 1922 and a substitute delegate in 1923. Providing extravagant hospitality to other delegates, Ranjitsinhji's delegation was popular and, according to Simon Wilde, "managed to acquire influence beyond its real status in Geneva".[223] Ranjitsinhji was assisted by his old friend and teammate C. B. Fry, who wrote his speeches. One such speech in 1923, made on behalf of the British Empire, was partly responsible for the withdrawal of the Italians from Corfu, which they had occupied. He also made a controversial speech in 1922 against the limits placed on the immigration of Indians into South Africa.[224]

In 1927, Ranjitsinhji came under attack from the All India States Peoples Conference which accused him, among other things, of being an absentee ruler, high taxes and restricting liberties. He responded through supporting published works by different authors, including Jamnagar and its Ruler in 1927, Nawanagar and its Critics in 1929 and The Land of Ranji and Duleep in 1931. Although not entirely accurate, they attempted to answer some of the criticisms.[225] Ranjitsinhji visited England in 1930, to take part in talks on India's constitution. While there, he was well received by former cricketers and saw Duleepsinhji score 174 against Australia in a Test match at Lord's. At the request of Sussex, he was president of the county for the year.[226] He continued to oppose Indian federation, despite support for the idea from the British and some of the princes. He was chancellor to the Chamber of Princes in 1933, shortly before he died.[227]

Ranjitsinhji died of heart failure on 2 April 1933 after a short illness. McLeod recounts that "many" contemporary observers attributed Ranji's death to an angry comment made publicly by Lord Willingdon, the Viceroy of India in the Chamber of Princes.[228] Ranji had felt that he was speaking in defence of British interests and, The Morning Post said, "Feeling himself rebuked by the Power he wished to save, ... he lost all desire to live".[228] Whether or not the dispute was the catalyst for his final illness, Ranjitsinhji's health had gradually deteriorated in his final years. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered over the River Ganges.[229] His estate in England was worth £185,958 at his death.[229]

Playing style

In his day, Ranjitsinhji's batting was regarded as innovative and history has come to look upon him as "one of the most original stylists to have ever played the game".[230] His great friend and Sussex captain, C. B. Fry commented on Ranji's "distinctiveness", attributing it to "a combination of perfect poise and the quickness peculiar to the athletic Hindu".[230] Neville Cardus described English cricket, before the arrival of Ranjitsinhji as "English through and through", but that when Ranji batted, "a strange light from the East flickered in the English sunshine".[231] Wisden editor and cricket critic Steven Lynch says that "everything seems possible" for him while playing on a fast wicket.[232]

Titles

His full title was Colonel His Highness Shri Sir Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji II, Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, GCSI, GBE.

Legacy

Bateman's work on cricket and the British Empire identifies Ranjitsinhji as an important figure in helping build "imperial cohesion", adding that his "cultural impact was immense".[233] Bateman identifies in particular the use of Ranji's image during his era in advertising in England and Australia.[233] This was a marked turnaround from the racism Ranji had faced early in his career, which he had tried to overcome with techniques such as adopting the pseudonym, "Smith".[81]

The popularity of an Indian playing cricket in England and for England was remarked upon during Ranjitsinhji's era. W. G. Grace directly linked Ranji's celebrity to "his extraordinary skill as a batsman and his nationality".[230]

After his death, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) started the Ranji Trophy in 1934, with the first fixtures taking place in 1934–35. The trophy was donated by Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, who also inaugurated it. Today it remains a domestic first-class cricket championship played in India between different city and state sides.[234]

As a ruler, his legacy is more patchy. McLeod summarises his achievements at home as "remodelled his capital, constructed roads and railways, and built a great port with modern facilities".[235]

Notes

- Ranjitsinhji's name includes the Gujarati suffix -sinhji, composed of two separate elements: -sinh, a cognate of Singh (a name common amongst the Rajputs of Gujarat ), and -ji, a general honorific. His name is less commonly given as Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji, which incorporates a patronymic derived from the name of his adoptive father, Jam Saheb Shri Sir Vibhaji II. During his playing career, Ranji was often recorded on scorecards as Prince Ranjitsinhji or K. S. Ranjitsinhji. The latter usage derives from the honorifics Kumar Shri, which were not his given names, but part of his title. The use of initials derived from the tradition of distinguishing amateur players from professionals – amateurs had their initials listed on scorecards, whereas professionals were denoted by only their surnames. He also played under the name Smith on occasion.[2]

- Among the claims against Jaswantsinhji's mother were that she was ineligible for marriage to Vibhaji as a Muslim, that she was pregnant before meeting Vibhaji,[19] and that she was a prostitute.[10] Part of the reason for these claims was that many Rajput's believed that, for Vibhaji, only marriage to another Rajput was acceptable.[19]

- Many matches were played with fifteen players on a team, the bowling was underarm and the laws of cricket were not strictly enforced.[23]

- At the time, the team for each Test was selected by the committee of the county team whose home ground hosted the match; the MCC chose the team for the Lord's match and the Lancashire committee selected for the Old Trafford match.[82]

- The book was released at the time of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. The choice of title and a dedication to the Queen were probably to generate more interest in the book.[98]

- Bobby Abel equalled the record in the same match and surpassed it by scoring his twelfth century in the following fixture.[136]

- Percy Standing, in a 1903 biography of Ranjitsinhji, claimed the visit was in response to Rajinder Singh's death, although this event happened 13 months earlier.[141]

- Tayler discovered this upon reading of MacLaren's appearance in court over the non-payment of rent. MacLaren claimed that as Ranjitsinhji paid, he could not be prosecuted as a sovereign, but the magistrate ruled that MacLaren was responsible and so had to pay.[188]

- Evidence for this includes a makeshift corridor built between Ranjitsinhji's rooms and those of the housekeeper, where Edith Borrisow may have stayed. Ranjitsinhji also possessed a marble bust of a woman whom Simon Wilde believes may have been Borrisow.[206]

- Ranjitsinhji later wrote to Berthon stating he had forgotten to bring money and asking for £1,000. Berthon informed him the state did not have that amount of money.[207]